Defining Nature and Biodiversity

“Nature” refers to the natural world and includes non-living things (such as water, air and soil) and living things (such as plants, animals (including people) and fungi). People and society, including corporates and financial institutions contribute to and are affected by nature – we have to recognise that we are embedded in nature and depend upon it for our survival. “Natural capital” can be described as the stock of renewable and non-renewable resources (e.g. plants, animals, air, water, soils, minerals) and services from which business and societies benefit.

“we must fix our relationship with the natural world or destroy human prosperity, well-being and our future. And it is with this knowledge in hand that in 2021 we must seek to join up the climate and nature agendas, and arrive at an ambitious, measurable and accountable post-2020 global biodiversity framework. To secure nature is to invest in our own self-preservation.” Inger Andersen, UN Under-Secretary-General and Executive Director of the UN Environment Programme.

In the same breath as nature, we often refer to “biodiversity” but this is slightly different. It refers to the wide array of biological life on Earth. We can observe biodiversity at two levels, in the genetic variation of species in a population (think farming and the narrow range of species which are produced) and in the variety of functions that different species perform in an ecosystem. For this reason, a common metric for biodiversity is the number of species present in an ecosystem. No one knows the number of species on Earth but around 1.2 million have been described by scientists and estimates of the total number range from 8 million to 100 million species. The Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF) states that “An average of around 25 per cent of species in assessed animal and plant groups are threatened, suggesting that around 1 million species already face extinction, many within decades, unless action is taken to reduce the intensity of drivers of biodiversity loss”. Biodiversity is important because the more biodiversity there is in an ecosystem, the more productive that ecosystem is, and the more resilient and adaptable that ecosystem is in the face of climate and other change.

Why do nature and biodiversity matter?

In the last few years, the focus of governments and business has been on climate change. Following the adoption of the Paris Agreement in 2015, we have seen a global drive to reduce greenhouse gas emissions to reach net zero emissions to limit the impacts of climate change, to avoid, amongst other things, increases in extreme weather which will affect food generation, reduce freshwater availability, bring ecosystems to collapse and cause widespread flooding and wildfires. But we are in the middle of a twin climate-ecological crisis. Climate change and biodiversity loss are interconnected. Loss of biodiversity is a cause of climate change and restoration of biodiversity is a big part of preventing climate change. In December 2022, the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF) was adopted at COP 15. The GBF aims to halt and reverse nature loss and sets out global targets to be achieved by 2030 to safeguard and sustainably use nature and “relies on action and cooperation by all levels of government and by all actors of society”.

At this juncture, given the interconnectedness noted above, biodiversity and climate change arguably need to be tackled together, making biodiversity restoration a key part of climate change solutions and ensuring that biodiversity does not become a victim of those solutions. Poor alignment can lead to ecosystem destruction, including for example cases of deforestation to accommodate new solar farms, siting wind farms on bird migration paths, leading to the death of many birds, and disruption of aquatic ecosystems, flooding and blocked fish migration from hydropower. We risk accelerating nature’s destruction unless biodiversity and ecosystems are fully considered in development decisions around climate change solutions, including wind, solar and hydropower facilities.

The extent of biodiversity loss is visually depicted in the “Biodiversity Stripes” below (showing global biodiversity loss between 1970 and 2018). The stripes were developed by Professor Miles Richardson et al of the University of Derby. Using data from the Living Planet Index they show an average population drop of 69% globally in mammals, birds, fish, amphibians and reptiles since 1970. In 2019, Rockström et al suggested in “A safe operating space for humanity” that biodiversity loss (based on extinction rate) is occurring at a rate not seen since the last global mass-extinction event and has already reached levels which the Earth cannot sustain without “significant erosion of ecosystem resilience”.

So it is clear that the rate of biodiversity loss is dangerously high and businesses need to act now. But how is biodiversity loss linked to business risk? Almost all businesses have a direct or indirect link to nature. Using a simple food industry example to demonstrate this linkage – if a driver of change, such as climate change, occurs one consequence would be strain on ecosystems which can result in a loss of a species, such as a honeybee (biodiversity loss). Honeybees (and many other types of bee and flying insects) provide nature services in the form of pollination. Decline in these species results in reduced rates of crop pollination. Agricultural and food sector businesses are consequently negatively impacted due to reduced production and even crop failures, supplies may have to be obtained from more expensive and/or distant sources, or may not be available at all. This is one example of how changes in nature impact businesses’ everyday activities. Nature-related risks are also closely connected to climate-related risks: ecosystems both emit and sequester carbon dioxide. The Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures framework (TNFD) explains much more about the risks and their interconnection here. The intention is that the TNFD provides a framework for entities to consider and disclose nature-related risks affecting their business, alongside their climate-related risk reporting.

What is TCFD and how is it different to TNFD?

The Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures provides a reporting framework for climate-related financial disclosure. It already applies in the UK and other countries, see here and here for more information.

On 18 September 2023, we expect the final version of the TNFD framework to be published. The TNFD builds on the existing structure of the TCFD, using the same categories of governance, strategy, risk management and metrics and targets for purposes of reporting on nature-related risks for business. As with TCFD, the intention is that the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) standards and guidance will be aligned with the TNFD, leading to a simpler, more streamlined approach. It is expected that TNFD will be supported globally and the disclosure obligations will be introduced into national disclosure regimes as TCFD has been.

How has the TCFD framework evolved from the TNFD framework?

The TNFD framework was based on TCFD framework to provide a familiar structure and to provide continuity in disclosure of climate-related risks, which will now form a part of “nature-related risks”. In the short term, as with any change in reporting standards, the TNFD will cause upheaval as entities come to terms with the wider scope of disclosures. In the long-term it provides a framework (not a standard) for businesses to assess, disclose, measure and reduce their nature-related risks.

The key differences between TCFD and TNFD include:

- Greater emphasis on the location of assets and/or activities in the TNFD in order to accommodate specific considerations arising from regional/country differences;

- The TNFD includes nature-related metrics which are holistic and much more complex than those included in TCFD; and

- Organisations will need to disclose how affected stakeholders are engaged in the assessment of, and response to, nature-related dependencies, impacts, risks and opportunities.

Thinking beyond climate-related risks – applying LEAP

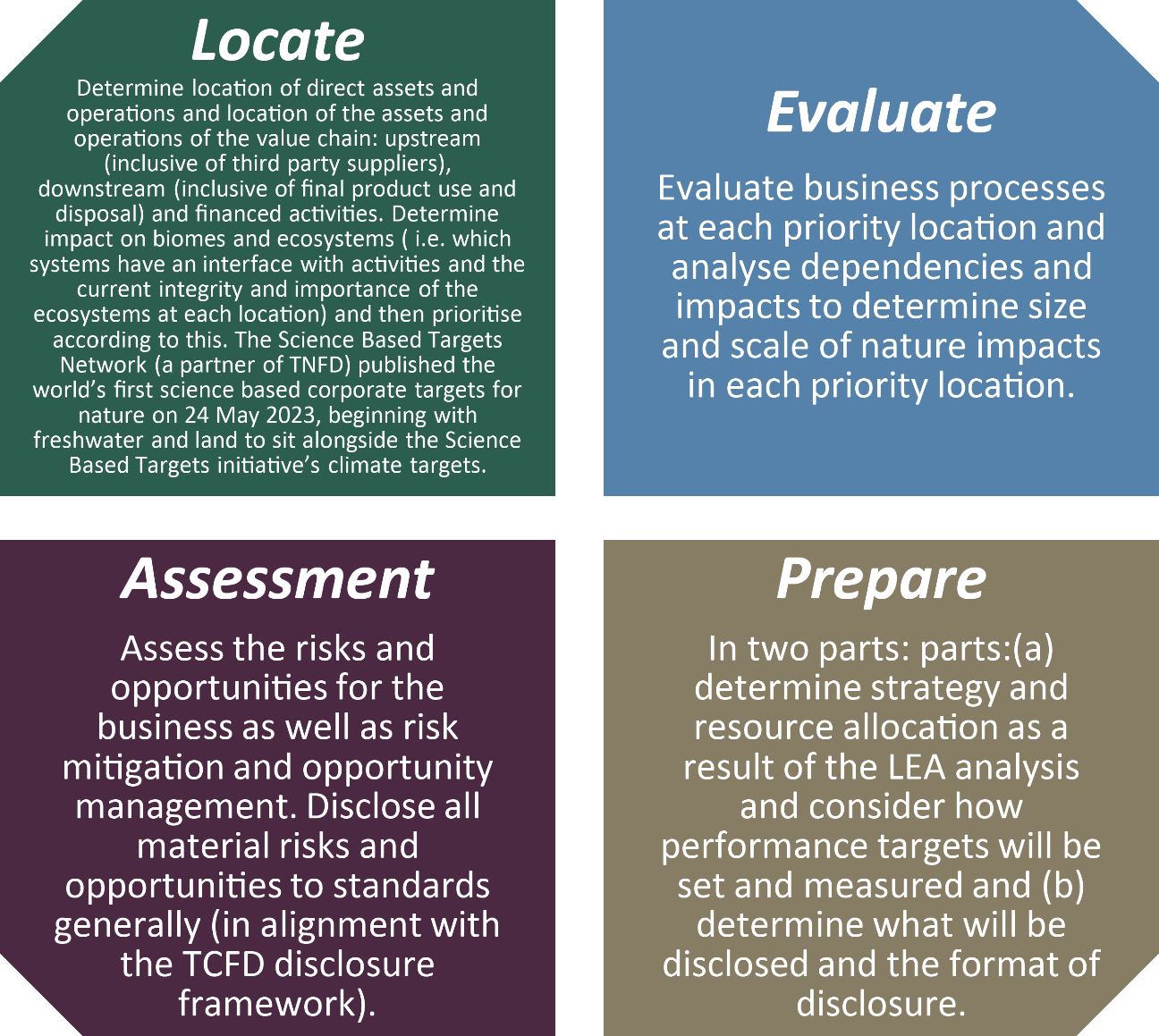

TNFD provides a voluntary approach for scoping which nature-related risks businesses need to focus on for assessment purposes called “LEAP”: locate, evaluate, assess, prepare, including different approaches designed for corporates and financial institutions (FIs) (being banks, insurance companies, asset managers, asset owners and development finance institutions).

The TNFD continues to require examination of a subject organisation's direct operations, together with their upstream and/or downstream and/or financed impacts and dependencies where relevant, that are in priority areas. This reflects the scope 1,scope 2 and scope 3 carbon emissions associated with the TCFD.

The LEAP-FI process (for FIs) recognises that for FIs the impact of nature on their own operations and supply chain will be negligible in comparison to their financed activities. They are advised to encourage their clients to apply the LEAP approach for corporates and report information in line with TNFD disclosure recommendations. Such data supplied to FIs can be used to complement other sources of data such as proxy data from public and private sources, ultimately enabling FIs to produce their own aggregated reporting on a well-informed basis.

The below summarises the four steps of LEAP:

Next steps

FIs can expect TNFD-aligned reporting to become mandatory in the medium term, and similar to the process around integration of TCFD reporting, will do well to get ahead of the game. Whilst the framework is familiar and the internal process and governance pathways required to implement these types of reporting enhancements are becoming increasingly well-worn, the skills and expertise required in connection with TNFD will be different to what has gone before.

FIs will now need to ensure that they have sufficient expertise and capacity in their workforce to consider and analyse nature-related risks in line with TNFD. They will also need to build relationships and engage with upstream, downstream and financed organisations to ensure that those value and financing chain participants understand their own nature-related dependencies, and impacts as well as risks and opportunities and FIs will need to encourage them to disclose in line with TNFD. Once there is a better understanding of the dependencies, impacts, risks and opportunities, FIs can start to decide on targets and how they will measure progress.

Organisations which report under the EU Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive will have separate obligations to make biodiversity-related disclosures. Whilst harmonisation is at the fore of people’s minds, it remains to be seen whether this will be achieved in practice.

Time is short to get to grips with these new concepts.

References

1 Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, Introductory Sections, 22 February 2023.

2 Data: LPI 2022. Living Planet Index database; 2022 https://stats.livingplanetindex.org/; Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, UK. 2021. The #BiodiversityStripes website can be found at https://biodiversitystripes.info/global with a further breakdown by region. The global data includes over 30,000 populations of over 5000 species.

3 “A safe operating space for humanity”, Rockström et al, 2009, Nature, 461, 472-47.