When is a combination of two separate treatments for a particular disease obvious-to-try, such that it is rendered obvious for the purposes of patentability? The Supreme Court answered this question in KSR Int'l Co. v. Teleflex Inc., 550 U.S. 398 (2007), when it said that "obvious to try might show that [the combination] was obvious . . . [if] there are a finite number of identified, predictable solutions." Id. at 421. Therefore, the answer appears to turn on predictability. Correspondingly, in its third Novo Nordisk A/S v. Caraco Pharm. Labs. Ltd. opinion, rendered earlier this week, the Federal Circuit found no error in the lower court's finding that the synergistic effects of two Type II Diabetes treatments were predictable, thereby rendering the combination obvious. However, at the same time, the Court appeared to criticize almost all of the studies by (or cited by) Novo that supported this "obvious" synergistic effect, and found that there were plenty of other studies that had contradictory results. This, of course, begs the question that, if such unexpected results were predictable before the invention, why were they so difficult to establish after the invention. Judge Newman provided a dissent to the obviousness determination because she felt that the lower court did not address the correct question: "whether it was obvious that the combination of metformin and repaglinide would exhibit synergism and that the combination would be 800% more effective than the additive effect of the components separately." She found sufficient evidence in the record to answer this question in the negative, and would therefore have upheld the validity of the patent.

As alluded to above, this Novo case has had an extensive history, including a stop last year at the Supreme Court. We provided analysis at the time of the Supreme Court's opinion (see "Caraco Pharmaceutical Laboratories, Ltd. v. Novo Nordisk A/S (2012)"), as well as the two previous Federal Circuit opinions (see "Novo Nordisk A/S v. Caraco Pharmaceutical Laboratories, Ltd. (Fed. Cir. 2010)" and "Novo Nordisk A/S v. Caraco Pharmaceutical Laboratories, Ltd. (Fed. Cir. 2012)"), so this post will only provide enough introduction for the proper context of this case. Novo markets the drug PRANDIN® for the treatment of Type 2 (adult-onset) diabetes. Repaglinide is the active ingredient in PRANDIN®, and the use of repaglinide in combination with metformin is covered by U.S. Patent No. 6,677,358 ("the '358 patent"). The previous Supreme Court decision stemmed from Caraco's ANDA filing to market a generic Repaglinide monotherapy, which contained a Section viii statement to "carve-out" the '358 patent's claimed method of use. However, because Novo had provided a use code for the Orange Book listing broad enough to cover the non-patented uses, the FDA rejected Caraco's carve-out label. Ultimately, the Supreme Court held that 21 U.S.C. § 355(j)(5)(c)(ii)(I) provided an ANDA applicant an opportunity to challenge inaccurate use codes and designations, and as a result, the use code for PRANDIN® now reads "Patented Method of Using Repaglinide in Combination With Metformin as Indicated For Improving Glycemic Control in Adults with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus." Nevertheless, according to statements made during the oral argument for the present case, Caraco had not been successful in receiving FDA approval for the Repaglinide monotherapy. Therefore, the validity of claim 4 of the '358 patent was apparently the only remaining obstacle for the approval of Caraco's ANDA.

As alluded to above, this Novo case has had an extensive history, including a stop last year at the Supreme Court. We provided analysis at the time of the Supreme Court's opinion (see "Caraco Pharmaceutical Laboratories, Ltd. v. Novo Nordisk A/S (2012)"), as well as the two previous Federal Circuit opinions (see "Novo Nordisk A/S v. Caraco Pharmaceutical Laboratories, Ltd. (Fed. Cir. 2010)" and "Novo Nordisk A/S v. Caraco Pharmaceutical Laboratories, Ltd. (Fed. Cir. 2012)"), so this post will only provide enough introduction for the proper context of this case. Novo markets the drug PRANDIN® for the treatment of Type 2 (adult-onset) diabetes. Repaglinide is the active ingredient in PRANDIN®, and the use of repaglinide in combination with metformin is covered by U.S. Patent No. 6,677,358 ("the '358 patent"). The previous Supreme Court decision stemmed from Caraco's ANDA filing to market a generic Repaglinide monotherapy, which contained a Section viii statement to "carve-out" the '358 patent's claimed method of use. However, because Novo had provided a use code for the Orange Book listing broad enough to cover the non-patented uses, the FDA rejected Caraco's carve-out label. Ultimately, the Supreme Court held that 21 U.S.C. § 355(j)(5)(c)(ii)(I) provided an ANDA applicant an opportunity to challenge inaccurate use codes and designations, and as a result, the use code for PRANDIN® now reads "Patented Method of Using Repaglinide in Combination With Metformin as Indicated For Improving Glycemic Control in Adults with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus." Nevertheless, according to statements made during the oral argument for the present case, Caraco had not been successful in receiving FDA approval for the Repaglinide monotherapy. Therefore, the validity of claim 4 of the '358 patent was apparently the only remaining obstacle for the approval of Caraco's ANDA.

Claim 4 of the '358 patent reads:

4. A method for treating non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus (NIDDM) comprising administering to a patient in need of such treatment repaglinide in combination with metformin.

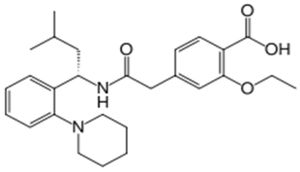

Repaglinide falls within the functional class referred to as "insulin secretagogues," which work by stimulating insulin release from pancreatic beta cells. There are two subclasses of secretagogues: meglitinides (of which repaglinide is an example) and sulfonylureas (of which glyburide is an example). However, according to a prior art article, Wolffenbuttel B.H.R. et al., Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 45(2):113-16 (1993), repaglinide "differs from the sulfonylureas in its molecular structure, profile of action, and excretion mechanism." For example, the structure of repaglinide is:

Metformin, on the other hand, falls within the functional class of "insulin sensitizers," a class which works to reduce insulin resistance by acting on the liver to reduce insulin production. This improves sensitivity in muscle and fat tissue.

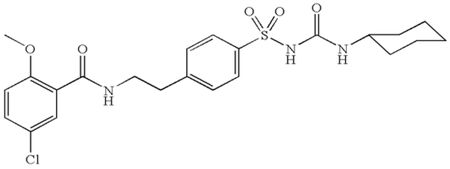

The structure of glyburide is:

Repaglinide was found to be rapid and short acting, and therefore quickly eliminated from the body. Therefore, its value as a pharmaceutical was questioned. Nevertheless, the inventors of the '358 patent conducted a study on Australian patients ("the Moses Study") which showed that, when given the combination of repaglinide and metformin, the fasting plasma glucose ("FPG") levels of patients that had failed on metformin alone decreased eight times lower than what was typically achieved by metformin alone. This was particularly surprising, because repaglinide on its own actually tended to increase patient's FPG levels. Therefore, the scientists concluded that the combination therapy yielded a synergistic effect (instead of an additive effect), because the effect of the combination exceeded the sum of the separately administered effect.

Based on the Moses study, Novo filed a provisional application, to which the '358 patent claimed priority. During prosecution of the resulting non-provisional patent application, the examiner rejected the claims four times, reasoning that it would have been obvious to try combining the two drugs, because it was predictable that there would be at least an additive effect. In its fifth response, Novo filed a declaration by Dr. Sturis, in which he disclosed results of a test with "Zucker obese rats." The rats were divided into four groups, one of which received a placebo, two of which received either repaglinide or metformin alone, and the last of which received the combination. The blood glucose levels were measured at various time points, and the area under the curve calculated. According to the results, the combination therapy proved to be more effective than the "hypothetical additive effect" of the two drugs, with a p-value of 0.061 (just shy of statistical significance). However, when the final time point of 120 minutes was considered alone, the p-value related to the synergistic effect was 0.02, in other words, it was statistically significant. The examiner withdrew the rejection based solely on Dr. Sturis' declaration, and the patent ultimately issued as the '358 patent.

As also alluded to earlier, Caraco filed an ANDA in 2005 requesting approval to sell a generic version of repaglinide. Caraco certified that that the '358 patent was either invalid or not infringed, and after Novo filed suit alleging that claim 4 was infringed, Caraco counterclaimed that the patent was, inter alia, obvious and unenforceable. The lower court sided with Caraco on both of these points, and Novo appealed.

As also alluded to earlier, Caraco filed an ANDA in 2005 requesting approval to sell a generic version of repaglinide. Caraco certified that that the '358 patent was either invalid or not infringed, and after Novo filed suit alleging that claim 4 was infringed, Caraco counterclaimed that the patent was, inter alia, obvious and unenforceable. The lower court sided with Caraco on both of these points, and Novo appealed.

Obviousness: Obvious to Try

Novo's strongest argument related to the obviousness of claim 4 was that the lower court did not properly review the scope and content of the prior art. Specifically, the lower court considered that the closest prior art was the combination therapy using metformin and sulfonylurea, but did not consider repaglinide's known efficacy as a monotherapy. The lower court justified its analysis because the sulfonylureas are secretagogues, just like repaglinide, and therefore repaglinide (supposedly) would have a similar mechanism of action. And, because the combination of metformin and one of the sulfonylureas were well known in the art to produce beneficial, and even synergistic, results, it would have been predictable that the claimed combination would also have had synergistic results, at least enough to make the combination obvious to try. The Federal Circuit found no clear error with this finding.

However, as highlighted by Judge Newman's dissent, repaglinide is not structurally similar to the sulfonylureas, and the action profile of these two subclasses in the body are different. Instead of finding support that these chemically distinct molecules would behave similarly on pancreatic beta cells, the District Court apparently assumed that because the effect that these two subclasses have on such cells is similar (stimulating insulin release), they must act in the same way. But the lower court apparently did not consider the Wolffenbuttel article, which suggested just the opposite -- that the two subclasses act differently. Also, according to Judge Newman, not all sulfonylureas exhibit synergy when combined with metformin, thereby making the predictability of the repaglinide/metformin synergy even more suspect. As Judge Newman put it, the District Court concluded that one skilled in the art would "perhaps" have expected the synergistic results of the claimed combination, but "perhaps" is not sufficient to overcome the clear and convincing evidentiary hurdle.

Perhaps more surprising, all of the studies that Novo cited as demonstrating the unexpected synergistic results were criticized by the District Court. Other than the Moses study, which showed an eight-fold reduction in FPG levels, the lower court did not find a single study that established that the repaglinide/metformin combination would be synergistic. For example, it was pointed out that the Sturis declaration study in rats did not result in a statistically significant outcome as the experiment was designed, and the only way to obtain a significant result statistically was to cherry pick the data from the last time point (120 minutes). In addition, another study (the Pfeiffer study) compared insulin sensitivity of eleven patients, and the combination therapy resulted in a 35% improvement over patients on metformin alone. However, these results were downplayed because of the small sample size. Even the Moses study itself was criticized because the near-term and long-term benefits observed were "generally inferior" to those of the combination of metformin with sulfonylureas. In fact, the lower court noted that other tests contradicted the positive results obtained from these three cited studies. It is curious that the lower court could have made a determination that such a synergistic result was predictable so as to make the combination obvious to try when it apparently had concerns with any study used to find unexpected result after the fact.

To be clear, the Federal Circuit thought that the record was clear that there were, in fact, synergistic results based on the combination. In fact, during oral argument, when Caraco's counsel appeared evasive on acknowledging that such synergistic results existed, Judge Newman told him that "[i]f your case turns on whether there is or is not synergism, I think you might as well sit down." Not to be outdone, during the same questioning regarding whether there were synergistic results, Judge Dyk exclaimed: "The answer is "yes," of course there is synergistic results . . . Why are you fighting that? Isn't that true? . . . The record establishes it, what are you arguing . . . I don't know why you are fighting this." Therefore, the only question should have been whether these synergistic results were predictable, and it is unclear that they were.

As Judge Newman pointed out, the lower court and the majority used the inventors' exceptional intellect against them, because they had tried this particular combination. However, the proper legal test is not whether it would have been "obvious to try" for the inventors, but rather whether one skilled in the art would have found the combination obvious to try. If the former were the case, Judge Newman explained, than "[s]uch a thesis would expunge patentability for all except random observations." It appears that the Court may have used hindsight reasoning to reach its conclusion, which is of course inappropriate.

Burden of Proof

Novo also argued that the District Court misallocated the burden of persuasion, thereby forcing Novo to "overcome" Caraco's "prima facie" case of obviousness. The argument was based primarily on the particular wording in the lower court's opinion. Nevertheless, the Federal Circuit did not agree. Instead, after Caraco had presented its case, Novo had the burden of production to come forward with evidence to rebut the "prima facie" case. Nevertheless, the burden of persuasion never shifted, remaining with Caraco to establish obviousness by clear and convincing evidence.

Deference to the Office

Novo finally argued that the District Court should have deferred to the examiner's original findings that the cited studies demonstrated unexpected results of synergy. As support, Novo cited to Kappos v. Hyatt, 132 S. Ct. 1690 (2012). However, the Federal Circuit pointed out that Novo inverted the holding of that case, which instead stated that no deference should be given to the Office's factual findings when those findings are contradicted by new evidence. Novo appeared to be suggesting that the reverse also holds, and that if there is no new evidence, there should deference given. This does not necessarily follow. But, more importantly, the Hyatt case, and others like it, were concerned with review of a PTO rejection in Federal Court, not with an alleged infringer's challenge to an issued patent. Instead, the presumption of validity applies to such a patent, but no additional deference to the Patent Office's findings need be given.

Inequitable Conduct

The lower court had also found that the '358 patent was unenforceable due to inequitable conduct during its prosecution. These allegations stemmed from the Sturis Declaration. Specifically, Caraco alleged that not informing the Patent Office that Dr. Sturis' original test protocol did not include looking at individual time points, and that therefore none of the findings originally sought were statistically significant, amounted to fraud on the Office. In addition, the prosecuting attorney, Dr. Richard Bork, made statements suggesting that the Sturis Declaration provides clear evidence of synergy, which according to Caraco overstated the evidence. Because the examiner acknowledged that the rejection was withdrawn because of the Sturis Declaration, Caraco continued, the Therasense "but for" materiality standard was satisfied. The District Court agreed with Caraco.

The Federal Circuit was less convinced. First, with regard to the Sturis Declaration, the Court found that the omission of the original test protocol was slightly troubling, but that it did not qualify as "but for" materiality. This was not a case in which adverse results were hidden in favor of more positive data. Nor did the omission undermine the opinion stated in the declaration. Bascially, Dr. Sturis was accused of failing to notify the Patent Office that the original test plan did not include the data calculation at 120 minutes. Even though this ideally should have been disclosed, the Federal Circuit found it to be a non-material omission. Moreover, with regard to Dr. Bork's statements during prosecution, the Court found them troubling but not material. Important in this determination was that Dr. Bork referred to Dr. Sturis' test results as "evidence" rather than "proof." In fact, during oral argument, the panel noted that such grandiose statements are often made by attorneys, and did not even Caraco's counsel make the same type of statements before the Court? Nevertheless, going forward, it is probably advisable for anyone prosecuting before the Office to speak of "evidence" when referring to test data, and to avoid making the conclusion that the data is definitive proof.

It would, therefore, appear that the saga of Novo v. Caraco is coming to a close. With claim 4 of the '358 patent invalidated, there would appear to be no more barriers remaining to the approval of Caraco's ANDA. Of course, there is always the possibility of another trip to the Supreme Court, however unlikely that may be.

Novo Nordisk A/S v. Caraco Pharmaceutical Laboratories, Ltd. (Fed. Cir. 2013)

Panel: Circuit Judges Newman, Dyk, and Prost

Opinion by Circuit Judge Prost; opinion concurring in part and dissenting in part by Circuit Judge Newman