LKQ Corporation, Keystone Automotive v. GM Global Technology Operations LLC

As an initial disclaimer, Irwin IP LLP is privileged to be lead counsel for LKQ Corporation and Keystone Automotive Industries, Inc. (collectively, “LKQ”) in several design patent infringement matters, including this case against GM Global Technology Operations and by extension General Motors Co. (collectively, “GM”). However, LKQ neither requested nor paid for preparation of this article, and the views expressed herein are those of the authors alone. Last year, the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (“CAFC”), agreed to rehear en banc LKQ’s appeal of the Inter Partes review decision by the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (“PTAB”) which held that U.S. Design Patent No. D797,625 (“the ’625 Patent”) was not unpatentable as obvious. This marked the first time that the CAFC granted such a petition in a patent case in over five years—or 15 years for a design patent case.

The current design patent obviousness analysis, the Rosen–Durling test (named for In re Rosen and Durling v. Spectrum Furniture), is the crux of the dispute. Rosen–Durling restricts the obviousness analysis for design patents unless a patent challenger can show that there is a single primary reference that is basically the same as the patented design and any secondary references used in combination with that “Rosen reference” must be “so related in appearance” so as to suggest their combination. LKQ argues that both prongs of this test constitute rigid rules that prevent courts and the patent office from considering what a designer of ordinary skill in the art (“DOSA”) would have found obvious. Rosen–Durling would therefore be inconsistent with the United States Supreme Court’s decisions in KSR v. Teleflex and Smith v. Whitman Saddle, 35 U.S.C. §103 (which governs the obviousness requirement for all patents), and the Intellectual Property Clause of the United States Constitution.

Ten of the active judges sitting on the CAFC, Chief Judge Moore, and Judges Stark, Hughes, Taranto, Prost, Lourie, Dyk, Reyna, Chen, and Stoll, heard oral argument from LKQ, GM, and the United States Government on Monday, February 5, 2024. Generally, GM advocated for the opposite of LKQ’s position, and the Government argued in favor of relaxing the Rosen step and abandoning the Durling step. The Judges’ questions and comments at oral argument seem to indicate that a change to design patent obviousness law may be on the horizon.

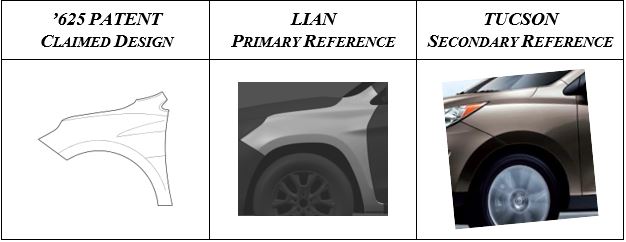

The PTAB found LKQ’s primary reference (“Lian”) failed to satisfy Rosen’s gating requirement that it be “basically the same” as the claimed design. Several judges suggested that, if so, the threshold was too demanding. Chief Judge Moore, for example, remarked “I look at both of these and they certainly give me the same visual impression….” And later: “I look at these things—no difference.” Judge Chen similarly noted: “they do look sort of the same, right? Lian and the claimed design?” And, following up on Judge Prost questioning the credibility of one of GM’s arguments, Judge Stark queried “how could either of those saddle references [in Whitman Saddle] be a Rosen Reference if the Lian reference here is not?” He continued: “if somebody tried to count the differences between the two references in Whitman Saddle and the claimed design, you would easily get to more than seven, starting with the fact that it’s a front-half, back-half situation…. I’m not sure how this is a credible argument.”

Doctrinally, the judges had even more to say about Rosen–Durling. Judge Chen questioned “the source of the legal authority the Rosen court had to articulate the basically the same command for a primary reference?” He commented: “there was no case before Rosen that mandated that requirement or articulated any version of that, certainly not the Supreme Court, and we know it’s not in the statute.” Then, Judge Dyk asked “…isn’t it true that neither Rosen nor Durling discussed Whitman Saddle?” When GM confirmed they did not, Judge Dyk noted that was “a problem.”

Indeed, some judges questioned how different the current obviousness test is from anticipation. Chief Judge Moore expressed concern with GM’s argument that a more sophisticated designer is less likely to find something basically the same: “you told me that, for example, in this art … it’s a sophisticated art with a lot of prior art, so designers are very attuned to the nuances and the differences. So that means you can get a patent on something an ordinary observer would have absolutely said is the same thing. … But that means you get infringement damages against people when the very same thing or very similar things may have been in the prior art and the ordinary designer, much more sophisticated, would have allowed you to get your patent. What do we do about that?”

It was clear by the judges’ questions regarding the analogous art doctrine, that they will consider this in any potential change. Chief Judge Moore explained that in the utility patent context, the analogous art doctrine guides against the risk of hindsight infecting the obviousness analysis and posed several questions as to how the analogous art doctrine would work in the design patent context. Later, Judge Hughes gave an instructive hypothetical: “Say you have… furniture designers, …and they routinely look to what’s happening in contemporary architecture to import designs from architecture to furniture. Wouldn’t that be something you could look to even though a design for a building is certainly not remotely in the same endeavor as a furniture designer?” Chief Judge Moore endorsed this as “absolutely correct.” Interestingly, Chief Judge Moore and Judge Stoll, who asked the most questions about analogous art, previously decided Airbus v. Firepass which held that analogous art is a fact question that hinges on record evidence of “the knowledge and perspective of an ordinarily skilled artisan.” 941 F.3d 1374, 1383-84.

The CAFC asked several questions of LKQ and the Government on how the USPTO could apply a new design patent obviousness test. Judge Prost summed up the issue: “the PTO take[s] issue with your willingness or advocacy for abrogating the threshold test by saying that … in litigation you get the benefit of design experts, but the examiners don’t have that…” But Solicitor Rasheed also stated “we think that our examiners are capable, as they are in the utility side, and as they already do on the design side, to look at the prior art and to figure out … who the person of skill in the art is and to proceed from there.”

One final note, Judge Chen asked if it were “true that only about one to two percent of all design patent applications get a prior art rejection during examination?” The Government indicated that their rate is “a little higher” and clarified “about 4%” after questioning by Judge Stoll. This statistic, which is vastly different for utility patents, is said by Professor Sarah Burstein to demonstrate that CAFC precedent makes it nearly impossible for the Patent Office to reject design patent claims (and by Professor Dennis Crouch as evidence that the Patent Office has abdicated its role in examination). See Sarah Burstein, Is Design Patent Obviousness Too Lax?, 33 BERKELEY TECH. L. J. at 608-610, 624 (2018); Dennis Crouch, A Trademark Justification for Design Patent Rights, 24 HARV. J. L. TECH. at 18-19 (2010).

It remains to be seen what change in the law the CAFC will make and to what degree, but now more than ever, LKQ v. GM is a case worth following. Stay tuned for additional entries in this series that will explore other areas of interest in this case.