Recently, the Federal Circuit has taken up issues relating to infringement under the doctrine of equivalents (DOE) and a related doctrine, prosecution history estoppel (PHE), that limits the scope of equivalents that can be asserted under DOE. See, e.g., Pharma Tech Solutions, Inc. v. Lifescan, Inc.; Amgen Inc. v. Coherus BioSciences Inc.; Indivior Inc. v. Dr. Reddy's Laboratories, S.A.; and UCB, Inc. v. Watson Laboratories Inc. In three cases (stemming in one instance from a Federal Circuit opinion consolidated from two cases in the district court, by Eli Lilly & Co. against two ANDA defendants), the defendants found to be infringers under the DOE have filed petitions for certiorari challenging how the Federal Circuit adjudged the interplay between the DOE and PHE in affirming the infringement determinations (see Eli Lilly & Co. v. Hospira, Inc. and Ajinomoto Co. v. International Trade Commission).

It will be recalled, by way of background, that the DOE arose in the modern era in Graver Tank & Mfg. Co. v. Linde Air Products Co., 339 U.S. 605 (1950), wherein the Supreme Court recognized that an "unscrupulous copyist" could practice a claimed invention without literal infringement in some circumstances, and as a consequence, the patent right could be turned into a "hollow and useless thing." But the doctrine fell into disfavor at the Federal Circuit during the 1990s and arguably provided the first inkling to the Supreme Court that the Federal Circuit's patent jurisprudence would benefit from closer oversight. In Warner-Jenkinson Co. v. Hilton Davis Chem. Co., and later in Festo v. Shoketsu Kinzoku Kogyo Kabushiki, the Supreme Court reiterated the vibrancy of the doctrine, Festo in particular setting forth the metes and bounds of the limitations PHE puts on the DOE. Specifically, the Court held that while any amendment to a claim element during prosecution raised a presumption that the applicant had relinquished all equivalents to the element, this presumption could be rebutted in three instances:

The equivalent may have been unforeseeable at the time of the application; the rationale underlying the amendment may bear no more than a tangential relation to the equivalent in question; or there may be some other reason suggesting that the patentee could not reasonably be expected to have described the insubstantial substitute in question.

The question of proper application of the "tangential relationship" test was at issue in each of the cases underlying the certiorari petitions. A brief background on the cases is set forth to provide the context for these petitions.

Eli Lilly & Co. v. Hospira

This decision arose in a consolidated appeal (Eli Lilly & Co. v. Hospira, Inc. and Eli Lilly & Co. v. Dr. Reddy's Laboratories, Ltd.) regarding infringement in ANDA litigation under the doctrine of equivalents of U.S. Patent No. 7,772,209, related to Lilly's anticancer drug Alimta® (pemetrexed disodium). The accused generic competitor drugs comprised a different salt, pemetrexed ditromethamine. During prosecution, Lilly had amended the claims to limit the pemetrexed salt species to the disodium salt itself.

The District Court held and the Federal Circuit affirmed DOE infringement, on the basis that the narrowing amendment had only a tangential relationship to the differences in these salts, the amendment being made to distinguish different antifolate species and not different salt forms thereof. Lilly did not dispute that its amendments satisfied the fundamental requirements of behavior that raises the estoppel: that "the amendment in question was both narrowing and made for a substantial reason relating to patentability." Lilly relied on the exception that the rationale for its amendments "[bore] no more than a tangential relation to the equivalent in question," citing Festo. Hospira and Dr. Reddy's Laboratories colorfully argued that "the tangential exception is not a patentee's-buyer's-remorse exception" and that the tangential relationship exception should be construed narrowly (themes that would recur in Hospira's cert petition). The Court agreed with the District Court's assessment that Lilly had narrowed the claims of the earlier, related application to overcome a rejection based on treatment with methotrexate, and that "the particular type of salt to which pemetrexed is complexed relates only tenuously to the reason for the narrowing amendment," which was to avoid prior art directed to methotrexate administration. The Court further reasoned that the exception itself "only exists because applicants over-narrow their claims during prosecution" and that "the reason for an amendment, where the tangential exception is invoked, cannot be determined without reference to the context in which it was made, including the prior art that might have given rise to the amendment in the first place." According to the panel, "[w]e do not demand perfection from patent prosecutors, and neither does the Supreme Court" (citing Festo). Lilly's burden was to show that pemetrexed ditromethamine was 'peripheral, or not directly relevant, to its amendment . . . [a]nd as [the panel] concluded . . . , Lilly [had] done so."

Ajinimoto v. ITC

Ajinomoto petitioned the International Trade Commission (ITC) under Section 337 (19 U.S.C. § 1337) for an exclusion order against CJ Cheiljedang for importing animal feed-grade L-tryptophan amino acid products produced by several different strains of Escherichia coli that infringed Ajinomoto's U.S. Patent No. 7,666,655. The claimed bacteria have been genetically engineered to increase L-aromatic amino acid production by fermentation, and in particular production of L-tryptophan. The basis for this increased production depends on an E. coli gene, yddG, encoding an aromatic amino acid transporter that causes the bacteria to excrete these amino acids into the culture medium. This is achieved in one of three ways: either by introducing (via plasmid transduction) additional copies of the gene into the bacteria (denoted as [3a] in the opinion); integrating additional copies of this gene into the bacterial chromosome ([3b]); or using a transcriptionally "stronger" promoter to express the endogenous yddG gene ([3c]). The full Commission reviewed and affirmed an ALJ's decision, of noninfringement of the imported products made by the earlier, [3a] strain, and reversed as to the ALJ's invalidity determination and noninfringement for products made using the later [3b] and [3c] strains under the doctrine of equivalents.

The Federal Circuit agreed, on the grounds that prosecution history estoppel did not bar a determination of infringement under the doctrine of equivalents based on the "tangential relationship" test. With regard to limitations introduced into the claims during prosecution regarding the second of the two later strains, the Commission had found that "the YddG protein encoded by the codon-randomized non-E. coli yddG gene of this strain [as practiced by the accused infringer] is an equivalent of SEQ ID NO:2" recited in claim 9.

CJ challenged this ruling on two grounds: that the amendments made during prosecution raised an estoppel against infringement under the doctrine of equivalents; and that the protein expressed in CJ's second strain failed to satisfy the "structure-way-result" rationale for infringement under the doctrine. Citing Festo Corp. v. Shoketsu Kinzoku Kogyo Kabushiki Co., 535 U.S. 722, 740 (2002), the majority recognized that the second of the three exceptions to PHE, that "the rationale underlying the amendment may bear no more than a tangential relation to the equivalent in question," was dispositive to the issue before the Court. The basis for the majority's view was that during prosecution, patentees made an amendment to distinguish over prior art that narrowed the scope of the claim from alternatives to the protein having an amino acid sequence identified as SEQ ID NO: 2 that differed by "deletion, substitution, insertion, or addition of several amino acids." The amendment changed the claim language to recite instead "a protein which comprises an amino acid sequence that is encoded by a nucleotide sequence that hybridizes with the [corresponding] nucleotide sequence of SEQ ID NO:1 under stringent conditions." The standard the Federal Circuit majority applied to determine whether the "tangential relationship" test is adequate to rebut the estoppel "focuses on the patentee's objectively apparent reason for the narrowing amendment." The majority held that Ajinomoto had satisfied this standard.

Judge Dyk disagreed, on the ground that the amendments to the claims of the '655 patent had a direct relationship to the elements at issue (non-E. coli YddG protein of CJ's second later strain) and thus L-tryptophan produced by either of CJ's later two bacterial strains did not infringe under the doctrine of equivalents (a rationale relied upon by all three of the Petitioners for certiorari).

Two of the certiorari petitions relate to whether the Federal Circuit properly applied the tangential relationship test to limit the effects of PHE on Lilly's claims reciting pemetrexed disodium. Although the arguments were similar (that the Federal Circuit had erred, that this was an important issue having wide import on innovation that the Supreme Court should address, and that this case was a proper vehicle for Supreme Court correction of the Federal Circuit's error), there are some informative differences.

Hospira's petition

The question presented is:

Whether a patentee may recapture subject matter via the doctrine of equivalents under the "tangential relation" exception by arguing that it surrendered more than it needed to during prosecution to avoid a prior art rejection, even if a claim could reasonably have been drafted that would literally have encompassed the alleged equivalent.

Hospira minces no words regarding its position, asserting that "[t]he Federal Circuit's tangentiality jurisprudence has gone seriously awry" because "the Federal Circuit now holds that even when the patentee indisputably could 'reasonably be expected to have drafted a claim that would have literally encompassed the alleged equivalent' . . . the doctrine of prosecution history estoppel applies so long as the patentee can show that its purpose for an amendment is sufficiently disconnected from its theory of equivalence." (The District Court based its opinion finding infringement under the DOE on the grounds that "the rationale underlying the amendment may bear no more than a tangential relation to the equivalent in question.") This way of applying the Supreme Court's Festo jurisprudence "unfairly skews the patent playing field in favor of patentees, by artificially expanding the scope of patent monopolies and handcuffing the ability of competitors to design their products in a manner that avoids infringement," in Hospira's view.

In this case, according to Hospira, Lilly's claims as filed encompassed all antifolates. Lilly amended the claim to pemetrexed disodium, which were the claims at issue in the underlying ANDA litigation. Hospira admits that its generic antifolate, pemetrexed ditromethamine, would have fallen within the scope of claims as filed directed to antifolates but not claims to pemetrexed disodium as granted. The Federal Circuit's error was permitting Lilly to expand the scope of its claims reciting pemetrexed disodium to encompass its antifolate. In Hospira's view "[t]his case should have been easy" because Lilly could have narrowed its claims to have literally encompassed Hospira's alleged equivalent (e.g., by amending to recite pemetrexed and its salts). Hospira argues that the Federal Circuit's affirmance of the District Court's DOE infringement decision is contrary to the Supreme Court's rubric in Festo that equivalents should be found under circumstances where a patentee "lacked the words to describe the subject matter in question." Rather, according to Hospira, the Federal Circuit used "Lilly's subjective goal in amending its claim . . . to distinguish pemetrexed compounds from other antifolates, not to distinguish one pemetrexed compound from another."

Hospira contends that the general importance of the Federal Circuit's decision, and the reason for the Court to grant certiorari, is the harm it does to the public notice function of claims (a concern the Supreme Court has recognized in its DOE jurisprudence; see, e.g., Hilton-Davis) ("There can be no denying that the doctrine of equivalents, when applied broadly, conflicts with the definitional and public-notice functions of the statutory claiming requirement," Warner-Jenkinson v. Hilton Davis Chem. Co., 520 U.S. at 29 (1997)), nullifying the claim-limiting effects of decisions applicants make during prosecution in order, inter alia, to overcome rejection over prior art. The Federal Circuit's decision permits applicants to play "bait-and-switch games" during prosecution, "making the strategic decision to narrow a claim during prosecution, then expanding the claim via the doctrine of equivalents by making post-hoc arguments about the reason for that narrowing" (emphasis in the petition), in Hospira's view.

According to the petition, the question before the Court is "when the record makes clear that the patentee could reasonably have been expected to have drafted a claim that would have literally encompassed the alleged equivalent, can the patentee nonetheless take refuge in the 'tangential relation' exception?" (The answer in Hospira's view is "no.") The Federal Circuit erred in looking at the purpose of the amendment rather than its effect, that purpose being to exclude antifolates other than pemetrexed from the scope of the claim. Lilly's amendment not only excluded other antifolates but excluded all antifolates other than pemetrexed disodium and thus Lilly should be estopped from asserting its claims against Hospira's pemetrexed ditromethamine. This is the Federal Circuit's legal error in applying PHE under the Court's Festo precedent. And the basis for this error was that the Federal Circuit put the patentee's interest over the public interest that PHE is intended to protect.

Finally, the petition contends that the Court should grant certiorari because "[the] question presented recurs frequently and is important to the sound administration of American patent law." The petition asserts (without citation) that "[i]t It is an unfortunate but routine tactic for patentees to narrow claims during prosecution in the Patent Office and then, after the patent is allowed, attempt to re-broaden them in the courts via the doctrine of equivalents" in support of its argument that the Court should grant its petition. What the petition does support with citations (nine of them) is that disputes like the ones before the Court here arise with sufficient frequency to support the Court's review (one of which is Ajinimoto and Judge Dyk's dissent consistent with Hospira's position here).

The petition completes its argument by identifying "internal inconsistencies" in Federal Circuit decisions involving the tangential relationship test (specifically citing Norian Corp. v. Stryker Corp., 432 F.3d 1356 (Fed. Cir. 2005)), as well as Felix v. American Honda Motor Co., 562 F.3d 1167 (Fed. Cir. 2009); Integrated Tech. Corp. v. Rudolph Techs., Inc., 734 F.3d 1352, 1358 (Fed. Cir. 2013); and Chimie v. PPG Indus. Inc., 402 F.3d 1371, 1383 (Fed. Cir. 2005).

Finally, Hospira argues that this case is the "ideal vehicle" because "the facts are remarkably stark" and the issue clear-cut.

Dr. Reddy's petition

Not surprisingly, Dr. Reddy's certiorari petition tracks Hospira's closely. The question presented by Dr. Reddy's is:

[W]hether, under Festo's "tangential" exception to prosecution history estoppel, patent owners may recapture subject matter they could have claimed in prosecution but did not, by arguing that they surrendered more than they needed to during prosecution to address a rejection by the Patent Office.

Slightly less aggressively than Hospira, Dr. Reddy's petition asserts that the Federal Circuit has "puzzled" over the proper application of the Festo tangential relationship test, and its cases have given two answers that are irreconcilable. This case is an "ideal vehicle" (because, truthfully, there are few alternative ways to make this important point to the Court) because the outcome below depended on which of these two rationales was used.

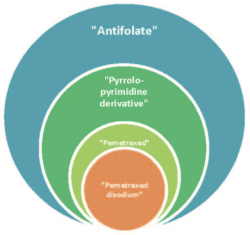

Like Hospira, Dr. Reddy's makes the case that Lilly made a strategic decision to narrow its claims to pemetrexed disodium (the active ingredient of its Alimta® drug product) rather than to alternative salts of the pemetrexed antifolate, illustrating these relationships with a helpful graphic:

Like Hospira, Dr. Reddy's declares that this should have been an "easy case" under Festo, because "Respondent could 'reasonably be expected to have drafted a claim that would have literally encompassed the alleged equivalent.'" Instead, Lilly in this case limited the claims excessively, to literally encompass only its active pharmaceutical ingredient, or API. This circumstance has arisen in other cases decided (reaching the opposite outcome) by the Federal Circuit, wherein the Court held that "a patent owner cannot invoke the tangential exception by arguing that, in hindsight, it surrendered more than it needed to address the Patent Office's invalidity rejection." The other line of precedent, which the Federal Circuit followed in this case, has held the opposite: that "[a] patent owner can invoke the tangential exception by arguing that, in hindsight, it surrendered more than it needed to address the Patent Office's invalidity rejection" (emphasis in petition). Dr. Reddy's petition calls this a "prosecution remorse exception" (language also present in its arguments below). And, Dr. Reddy's argues, the Federal Circuit's decision has the prejudicial effect on petitioners that they could not rely on the claim scope limiting amendments when developing their own drug with an antifolate that fell outside the literal scope of Lilly's claims.

The petition cites copious Supreme Court precedent on the importance of PHE to cabin the scope of DOE and provide a reliance interest in competitors regarding non-infringement of their products based on PHE (including Schriber-Schroth Co. v. Cleveland Trust Co., 311 U.S. 211, 220-21 (1940); Exhibit Supply Co. v. Ace Patents Corp., 315 U.S. 126, 136-37 (1942); Smith v. Magic City Kennel Club, 282 U.S. 784, 790 (1931); Weber Elec. Co. v. E.H. Freeman Elec. Co., 256 U.S. 668, 677-78 (1921); Morgan Envelope Co. v. Albany Perforated Wrapping Paper Co., 152 U.S. 425, 429 (1894); and Shepard v. Carrigan, 116 U.S. 593, 598 (1886)). As in Hospira's petition, Dr. Reddy also warns that failure to correct the Federal Circuit could lead to a situation where "the inventor might avoid the [Patent Office's] gatekeeping role and seek to recapture in an infringement action the very subject matter surrendered as a condition of receiving the patent," citing Festo.

Dr. Reddy's petition asserts the "internal division" at the Federal Circuit as a reason why the Court should grant certiorari (an argument that may have persuasiveness due to being the Federal Circuit's equivalent to a "circuit split" amongst the remainder of the Federal Courts of Appeal). The petition cites Federal Circuit cases illustrating the differences in various Federal Circuit judges' attitudes regarding the tangential relationship test starting with Festo and including Cross Med. Prods., Inc. v. Medtronic Sofamor Danek, Inc., 480 F.3d 1335, 1346-48 (Fed. Cir. 2007); Regents of Univ. of Cal. v. Dakocytomation Cal., Inc., 517 F.3d 1364, 1380-82 (Fed. Cir. 2008); Honeywell Int'l, Inc. v. Hamilton Sundstrand Corp., 523 F.3d (1304, 1321-22 (Fed. Cir. 2008); and Judge Dyk's dissent in the recent Ajinomoto case).

The petition synthesizes these disparate decisions into two "irreconcilable" approaches:

• Under one approach, the court asks why the patentee made the specific narrowing amendment it chose to make. See, e.g, Felix v. Am. Honda Motor Co., 562 F.3d 1167, 1184 (Fed. Cir. 2009); Amgen Inc. v. Hoechst Marion Roussel, Inc., 457 F.3d 1293, 1315 (Fed. Cir. 2006).

Under this approach, according to the petition, "the 'tangential exception' applies when an amendment adds multiple limitations to a claim at the same time, and not all relate to an examiner's rejection. The limitations unrelated to the examiner's rejection may fit the tangential exception," the petition noting that this was the approach followed by Judge Dyk's dissent in Ajinimoto. Relevant to the question presented here, the petition contends that "[w]here, as here, the patentee focused on a particular claim element, and responded to an examiner's rejection by narrowing in a way that excludes a defendant's allegedly equivalent product, the rationale for the narrowing amendment cannot be 'tangential' to the alleged equivalent," citing Honeywell Int'l, Inc. v. Hamilton Sundstrand Corp.

• Under the other approach, "[s]ome panels accept precisely the type of buyer's-remorse arguments that other panels reject and base the tangential-exception inquiry on a post hoc assessment of what the patent applicant needed to surrender to avoid an examiner's rejection. Those panels begin by phrasing the "reason" for the disputed narrowing amendment as surrendering only what was necessary to avoid a specific rejection—often to distinguish a particular piece of invalidating prior art," citing Insituform Techs., Inc. v. CAT Contracting, Inc., 385 F.3d 1360, 1370 (Fed. Cir. 2004) and Primos, Inc. v. Hunter's Specialties, Inc., 451 F.3d 841, 849 (Fed. Cir. 2006).

In such cases, the "unnecessarily surrendered claim scope is 'tangential' to that reason—without regard to the applicant's choice of how far to go in avoiding the examiner's rejection," citing Ajinimoto, Regents, and Primos. This was the approach taken in the case at bar.

These two approaches are "fundamentally irreconcilable" according to the petition. The petition is honest enough to admit that one approach (which it prefers) tends to result in PHE precluding a finding of infringement under DOE, while the approach taken by the District Court and Federal Circuit here tends to permit assertion of equivalents without prelusion by PHE. Yet the petition also asserts that "[b]oth approaches cannot be right, and the approach applied here is plainly wrong."

The petition also argues that the second approach (and necessarily the decision below) cannot be reconciled with Festo and other Supreme Court precedent. And perhaps at least equally importantly:

Under the approach the panel applied here, the public cannot objectively rely on narrowing amendments in prosecution to learn what a patent holder does not own. Patent owners will be able to argue—as Lilly did here—that the "reason" for any narrowing amendment was to avoid a particular rejection, and that any surrender of scope that was not necessary to that reason is "tangential." This invites precisely the sort of circumvention of the examination process that prosecution history estoppel is designed to prevent, where "the inventor might avoid the [Patent Office's] gatekeeping role and seek to recapture in an infringement action the very subject matter surrendered as a condition of receiving the patent," citing Festo.

The petition concludes that "[o]nly this Court can explain what it meant when it announced the "tangential" exception in Festo (noting elsewhere in the petition that the tangential relationship standard arose solely from the Court without any explication in its Festo decision) and in the face of 18 years of Federal Circuit decisions that have not resolved the issue. The petition emphasizes the importance of resolving the scope of the tangential relationship test by invoking the effects of uncertainty on "the ability of productive companies to determine their potential liability ex ante, before making substantial investments in competing products," including as examples that "[d]eveloping and securing FDA approval of a generic drug product, for example, typically costs millions of dollars"; "[a]nalogous costs for follow-on biologic manufacturers are hundreds of millions of dollars or more"; and "[a] new semiconductor plant costs billions of dollars." Under these circumstances, "[t]oo much uncertainty in the scope of patents chills beneficial investments in legitimate products, as recognized by the Court in Festo and Merrill v. Yeomans, 94 U.S. 568 (1876). And as has been noted in Hospira's petition, this case is "an ideal vehicle" for the Court to clarify the scope and application of the tangential relationship test because "the applicability of the tangential exception decides the entire case" and "this case cleanly exemplifies a recurring fact pattern in patent litigation: a patent applicant surrenders more than necessary to avoid a rejection in prosecution, then tries to recapture some of that claim scope in litigation."

CJ Cheiljedang's petition

The question presented is:

Whether, to avoid prosecution history estoppel under Festo Corp. v. Shoketsu Kinzoku Kogyo Kabushiki Co., "the rationale underlying the amendment" must be the rationale the patentee provided to the public at the time of the amendment.

While the facts in this case differ substantially from the Hospira and Dr. Reddy's petitions, the issue as set forth in the petition are strikingly similar: "the public's ability to rely on a patentee's representations to the Patent Office during prosecution (called the 'prosecution history') to determine the metes and bounds of a claim." But here the petitioner asserts that the Federal Circuit adopted a new rule, wherein the tangential relationship exception to PHE applies "even where the patentee gave no contemporaneous explanation in the prosecution history for why it chose the particular amended claim language or how the amendment overcame the rejection." This permits a patentee to expand the equivalent scope of amended claims "improperly" on a "post-hoc rationale" for any narrowing amendment, in light of the accused product, to enable the patentee to recapture scope voluntarily surrendered during prosecution. The result "creates perverse incentives at odds with the Patent Act's and this Court's focus on public notice" because it does not encourage transparency in patent prosecution but rather encourage an applicant to withhold any explanation for patent prosecution decisions in order to "craft with hindsight a rationale designed to be "tangential" to the alleged equivalent." The results, according to petitioner, will be "devastating" because "[t]he public will be denied notice of the actual scope of the surrender or what is subject to subsequent recapture as an "equivalent" until the end of infringement litigation, with the prospect of millions of dollars in damages and potential injunctions," analogous to indefiniteness in claims considered by the Court in Nautilus, Inc. v. Biosig Instruments, Inc., 572 U.S. 898 (2014).

Petitioner here analyzes the Federal Circuit's cases involving the tangential relationship test for PHE to have "specifically looked to the patentee's explicit explanation in the prosecution history of how its amendment overcame the rejection," citing Insituform Techs., Inc. v. CAT Contracting, Inc., 385 F.3d 1360 (2004); Regents of Univ. of Cal. v. Dakocytomation Cal., Inc., 517 F.3d 1364 (2008); and Intervet Inc. v. Merial Ltd., 617 F.3d 1282 (2010). In petitioner's view, the Federal Circuit "made a dramatic departure from [its] historical precedent" in its decision in Hospira and in this case. These decisions "significantly frustrate the public notice function of the prosecution history" and "allow a patentee to recapture claim scope it voluntarily surrendered during prosecution in order to secure allowance of its patent, despite the patentee's having provided no notice to the public that it intended to surrender any less than the entire territory between the original and amended claims." This creates uncertainty that Petitioner asserts will "stifle the progress of science and the useful arts" because "[p]otential innovators, who would otherwise be able to design around a patent, may instead decline to do so, unwilling to run the risk of being found to infringe under a doctrine of equivalents theory that recaptures what a patentee appears on the face of the patent and the prosecution history to 'have surrendered,'" particularly in the pharmaceutical industry due to high development costs, according to the petition.

The petition also emphasizes the important role PHE plays in the public notice function of patents, by striking a balance that "seeks to guard against [both] unreasonable advantages to the patentee and disadvantages to others arising from uncertainty as to their rights" citing General Elec. Co. v. Wabash Appliance Corp., 304 U.S. 364, 369 (1938). The apprehension PHE addresses is of early provenance in U.S. patent law, with the brief citing Evans v. Eaton, 20 U.S. 356, 434 (1822), for the proposition that a patentee cannot be permitted to "practi[ce] upon the credulity or the fears of other persons, by pretending that his invention is more than what it really is." The Court's jurisprudence regarding DOE is limited to particular circumstances where language is insufficient to "capture the essence" of the invention, according to petitioners. And because "the Court has always recognized that . . . the doctrine of equivalents 'conflicts with the definitional and public-notice functions of the statutory claiming requirement,' Warner-Jenkinson Co. v. Hilton Davis Chem. Co., 520 U.S. 17, 29 (1997), [the DOE] must be applied with restraint, so as not to stifle innovation." The petition applies these considerations to its argument for Supreme Court review, arguing that the Federal Circuit's decisions, in its case and in the Hospira case, has upset this balance by permitting patentees to supply post-hoc rationales in support of equivalents arguments, harming the public notice function of patents as cabined by PHE.

As in the other two certiorari petitions, this one maintains that the Federal Circuit's decision is an "ideal vehicle" for Supreme Court review, because the prosecution history is devoid of any argument or explanation as to "how its narrowing amendment overcame the prior art rejection, why it chose the amended claim language that it did, or whether it intended to surrender any less than the full territory between its original and amended claims," as Judge Dyk noted in his dissent (emphasis in petition). There is thus no need for the Court to weigh evidence or argument -- the issue is whether the Federal Circuit should have considered "post-hoc" rationales for the amendments at all, or found that the patentee could not bear its proper burden of overcoming the presumption that the narrowing amendment precluded a finding of infringement under the DOE.

Patentees in each case will have the opportunity to respond (if they so choose) and the Court will consider the petitions in due course over the next month or so, with argument in the Fall Term should the Court grant certiorari in any or all of them.