The intersection of patent law, drug regulations, creative lawyering, and commerce (if not outright greed) has once again arisen in a qui tam suit brought under 31 U.S.C. §§ 3729–3733 (alleging fraud against the U.S. Government) by Lower Drug Prices for Consumers (LDPFC), reportedly an arm of Foxhill Capital, in USA ex rel. Lower Drug Prices for Consumers (LDPFC) v. Allergan and Forest Labs, Case No. 16-cv-09 (E.D. Texas 2016). And if this plaintiff is successful it raises even greater risks to drug development than the continuing onslaught of inter partes review petitions by hedge fund managers, non-governmental organizations, gadflies, and others who would not have standing to challenge drug patents in court.

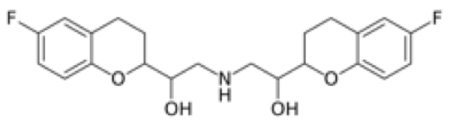

The case involves Orange Book-listed U.S. Patent No. 6,545,040 that covers the drug nebivolol, sold by Allergan and Forrest Labs as Bystolic® for the treatment of high blood pressure (it is a beta blocker) having the structure:

The basis of the suit are "overpayment and overcharges" made to defendants by the U.S. government, "directly or indirectly" through such programs as Medicare, Medicaid, the Children's Health Insurance Program, the Veterans' Administration, the military, prisons, and programs for Native Americans, according to the complaint. The alleged injury and fraudulent pricing is based on the defendants' exclusivity under the '040 patent, which "is an invalid patent that should never have been issued by the United States Patent and Trademark Office." Perhaps fortunately for these drug companies the term of this wrongful overpricing alleged by the complaint only commenced on June 2, 2015 when another patent on the drug, U.S. Patent No. 5,759,580, expired. The complaint alleges that defendants knew ("and would have been well-known to any company engaged in new drug research") that the patent was invalid. And it is on the basis for this allegation that the lawsuit, and plaintiff's potential liability for bringing it, will hang.

The '040 patent granted with six claims, claim 1 being representative and reciting the drug itself ([2R,αS,2′S,α′S]-α,α′-[iminobismethylene]bis[6-fluoro-3,4-dihydro-2H-1-benzopyran-2-methanol]). According to the complaint, these claims have been invalidated abroad (including in the UK) and challenged in ANDA litigation against seven generic companies (including Amerigen Pharmaceuticals, Glenmark Pharmaceuticals, Hetero Labs, Torrent Pharmaceuticals, Watson Laboratories, Alkem Laboratories, and Indchemie Health Specialties), each of which settled their litigations with Allergan/Forrest. The complaint alleges that these settlements are under scrutiny by the Federal Trade Commission but whether this extends further than the review of ANDA settlements by the FTC prescribed by the Medicare Modernization Act of 2003 is not described in the complaint. Plaintiffs allege that they have performed independent investigations, supported by expert declarations by Dr. Daniel W. Armstrong and Dr. Ronald W. Millard as well as 53 documents "found or created" by LDPFC in its investigation prior to filing the complaint. Specifically, the complaint alleges that the claimed stereoisomers encompassed by claim 1 of the '404 patent were disclosed four years earlier than the patent's filing date, in U.S. Patent No. 4,654,362 (albeit as a mixture of other stereoisomers). The complaint acknowledges that the question then becomes whether it would have been obvious to separate the isomers, and asserts the Federal Circuit's decision in Aventis Pharma Deutschland GmbH v. Lupin Ltd. (Fed. Cir. 2007), in support of its allegation that the claims are invalid for obviousness. This portion of the complaint (¶¶ 32-45) overstates the holding of the Aventis case, applying it for the proposition that any separation any mixture of stereoisomers is per se obvious, provided there was motivation to do so. And while the complaint (and expert declarations) focus on the routine nature of attempting to separate enantiomers, the only reference to whether the skilled worker would have had a reasonable expectation of success in doing so is recited in the negative (the result "would not have been [] unexpected").

These paragraphs (and the supporting documents and declarations) constitute all the support for the obviousness argument raise in the complaint. The remainder of the allegations arise from the assumption that they are sufficient, and thus that defending their patents and maintaining the branded price constitutes "false claims" against the U.S. government (¶¶ 46-50) for "an inflated and false overprice" for the drug (¶ 47). And while the complaint also alleges that the patentees "fail[ed] to supply all relevant information to the [USPTO]" there is no specific allegation that the patentee(s) are guilty of inequitable conduct. The complaint also casts the confidential nature of the invalidity contentions by each of the ANDA defendants in a negative light (¶¶ 51-56), asserting that this (court-ordered) confidentiality "kep[t] the otherwise public invalidity contentions hidden from the public and the federal government" (¶ 54).

The motivation for the suit becomes abundantly clear in the Prayer for Relief, which includes "actual damages, treble damages, and/or civil penalties between $5,000 and $10,000 for each violation [i.e., each pill sold] of 31 U.S.C. §§ 3729(a)(1)(B)," plus attorneys' fees, costs and expenses, and interest, and asks that, should the U.S. government intervene that plaintiffs get "at least 15% and not more than 25% of the proceeds of any judgment or settlement, and if the government does not intervene, at least 25% but not more than 30% of such proceeds.

It remains to be seen whether the lawsuit "has legs" or will be subject to a motion to dismiss on any number of grounds, particularly because the PTAB ruled against the petitioner and refused to institute an IPR; after all, if a petitioner cannot prevail under the relatively lax standards before the Office, including no presumption of validity and the "broadest reasonable interpretation" standard for claim construction, it is unlikely that a district court will find otherwise. It is important to note that the asserted basis for the action is that allegations of invalidity in Hatch-Waxman ANDA litigation provides the mens rea behind the qui tam action. If mere allegations of invalidity are enough then no patent involved in any regulated industry will be safe from someone somewhere deciding that the "bounty" provided by the statute is sufficient incentive to bring suit. A similar pattern emerged a decade ago for "false marking" claims, based on marketing patented goods in commerce where the patent had expired (yet the marking continued). There, the inducement was the risk that even a small penalty could amount to a large fine in aggregate (for example, for the sale of millions of consumer items annually). The current foray is more pernicious, because in the former case the tort (insofar as there was one) was patent: the items continued to be marked and sold after the patents had expired. Here there is no such certainty, and the circumstances are certainly ripe for the type of trolling activities that the high tech industry has spent a decade bemoaning (with varying levels of justification). Congress solved the last qui tam problem by changing the statute to require injury and standing; perhaps Congress should consider a similar change in the law here, not just for qui tam actions but for IPRs in general. At least that would restrict challengers to those with a real interest in reducing drug costs the old fashioned way, by providing generic drugs and not by clever (ab)uses of the legal system to fashion themselves a financial jackpot.

Hat tip to Dennis Crouch for making us aware of this complaint (see "Bad Patents and the False Claims Act")