- Mischief Afoot: Vans Kicks MSCHF’s Main Defense to Trademark Infringement to the Curb in Art Sneaker Dispute

- Ex-MLB Pitcher Brings the Heat in Successful Licensing Suit

- New York State Gaming Commission Cashes Out $15 Million Enforcement Prize over Fantasy Sports Site’s Violation

- Overtime: A Significant Step towards an English Football Regulator – Football Governance Bill Introduced in Parliament

Mischief Afoot: Vans Kicks MSCHF’s Main Defense to Trademark Infringement to the Curb in Art Sneaker Dispute

If the shoe fits, wear it. Or so the Second Circuit mused in a recent decision, in which it “re-boxed” an art collective’s appeal challenging a preliminary injunction that barred further sales of a limited-edition art sneaker. In its decision, the appeals court relied on the recent Supreme Court Jack Daniel’s trademark decision that found works cannot qualify for increased First Amendment protection as “expressive works” for purposes of the Rogers test when they make unauthorized use of others’ trademarks for source identification purposes. (Vans, Inc. v. MSCHF Product Studio, Inc., 88 F.4th 125 (2d Cir. 2023)).

MSCHF Product Studio, Inc. (“MSCHF”) is a Brooklyn-based anti-establishment art collective that uses artwork as commentary that tries “to start a conversation about consumer culture…by participating in consumer culture.” To this aim, MSCHF has produced a variety of limited edition products, including prior sneaker collaborations with music artists and a work of art called “The Persistence of Chaos” consisting of a laptop infected with six computer viruses and other historical malware (that sold at auction for more than $1.3 million). MSCHF ordinarily produces limited quantities of its products and sells them during prescribed sales periods (or “drops”).

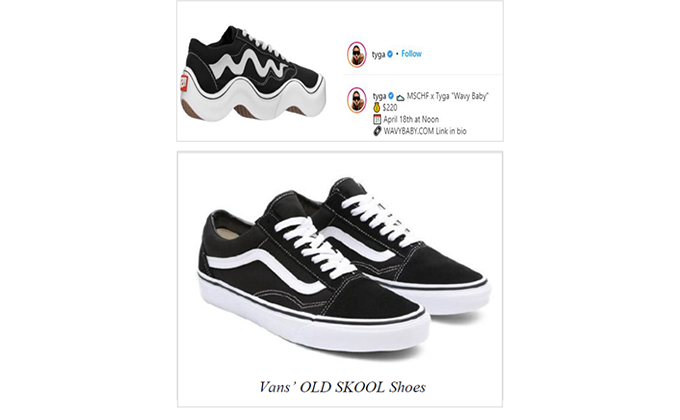

MSCHF piqued Vans’ attention in early 2022 after they announced the “Wavy Baby” sneaker release, which they collaborated with rapper Tyga to create, promote and sell. By their own admission, MSCHF modeled the Wavy Baby after the “most iconic, prototypical” skate shoe: the Vans “Old Skool.”

[See below images comparing the two sneakers].

[Source: Vans’ Complaint]

[Source: Vans’ Complaint]

MSCHF scheduled the Wavy Baby drop for April 18, 2022, and began promoting the shoes in collaboration with Tyga. In response, Vans promptly sent both MSCHF and Tyga cease and desist letters, which were ignored. Vans then put its foot down and filed a complaint on April 14, 2022, requesting, among other things, injunctive relief blocking the Wavy Baby release, as Vans perceived the shoes to be infringing various trademarks related to the Old Skool sneaker.

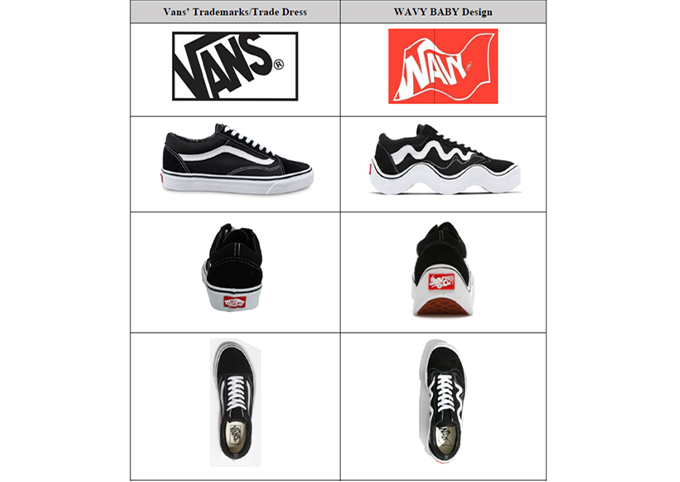

[See the following image comparing the design of both sneakers].

[Source: Vans’ June 20, 2023 Letter Brief to the Second Circuit].

[Source: Vans’ June 20, 2023 Letter Brief to the Second Circuit].

Vans subsequently filed a motion for a temporary restraining order and a preliminary injunction, in which it asked the district court to enjoin MSCHF from: releasing the shoes for sale; fulfilling orders for the shoes; using Vans’ Old Skool trade dress, marks, or confusingly similar marks; and from using any such marks in any advertising, marketing or promotion. Unwilling to wait, MSCHF proceeded with the Wavy Baby drop as scheduled and purportedly sold all 4,306 pieces of the limited-edition Wavy Baby art shoes in one hour. MSCHF then filed opposition papers to Vans’ motion that stated, based on the response it had gotten from buyers and interested fans, it was not “aware of any collector who bought or tried to buy a Wavy Baby and thought they were buying a Vans shoe.”

A New York district court quickly laced up and granted Vans’ request for a temporary restraining order and preliminary injunction barring MSCHF from fulfilling orders for the Wavy Baby shoes and essentially freezing its revenues from the Wavy Baby, among other relief. The lower court found that Vans had presented enough evidence of consumer confusion and had therefore shown a likelihood of success on its trademark claims. Further, the court rejected MSCHF’s First Amendment defense and concluded that the shoes failed to meet the requirements for a successful parody because “the Wavy Baby shoes and packaging in and of themselves fail to convey the satirical message.” Wanting to put the shoe on the other foot, MSCHF appealed to the Second Circuit. In its appeal MSCHF argued that Vans’ claims were precluded by the First Amendment.

The primary function of a trademark is to identify the source of goods or services, which is important, in part, because it enables consumers to make informed purchasing decisions. Per the Supreme Court, the “cardinal sin” under trademark law is thus to “confuse consumers about source — to make (some of) them think that one producer’s products are another’s.” Befitting that, in federal trademark infringement cases brought under the Lanham Act, courts generally use a multifactor test to make an inquiry into the allegedly infringing trademark use and whether the defendant’s actions are “likely to cause confusion” or otherwise cause mistake or deceive as to the affiliation, connection or association of the defendant's goods or services with those of the plaintiff.

As the Second Circuit noted, the traditional consumer confusion inquiry may be applied more narrowly if the allegedly infringing good or service is a work of "artistic expression." Under the Rogers test (derived from a 1989 Second Circuit decision, which has been widely adopted in other circuits), the Lanham Act and the accompanying multifactor infringement analysis will apply to artistic works only where the public interest in avoiding consumer confusion outweighs the public interest in free expression. Thus, the Rogers precedent states that the Lanham Act should not apply to "artistic works" as long as the defendant's use of the mark is (1) artistically relevant to the work, and (2) not "explicitly misleading" as to the source or content of the work. In arguing that it was entitled to the heightened First Amendment protections of the Rogers test, MSCHF in essence asserted that the Wavy Baby sneakers are expressive works and that it did not use the Vans marks to designate the shoe’s source but solely to perform another expressive function.

The natural question arising from this assertion is how an expressive work is defined. In hearing the appeal, the Second Circuit was faced with the core issue of “whether and when an alleged infringer who uses another’s trademark for parodic purposes is entitled to heightened First Amendment protections, rather than the Lanham Act’s traditional likelihood of confusion inquiry.” To decide this issue, the appellate court looked to a recent Supreme Court ruling in Jack Daniel’s Properties, Inc. v. VIP Products LLC, 143 S.Ct. 1578 (2023). In that case, VIP Products created a plush dog toy called “Bad Spaniels” (a play on “Jack Daniel’s”) that was designed to look like a Jack Daniel’s whiskey bottle, but with a variety of dog-related changes. Jack Daniel’s alleged the dog toys infringed its trademarks and the case made its way up to the Supreme Court.

Like MSCHF, VIP Products argued that its use of the Jack Daniel’s trademarks was entitled to review under the Rogers test and therefore the Court should sideline the likelihood of confusion test. The Supreme Court disagreed, holding that VIP Products used the trademarks as trademarks, that is, to identify the source of its own products. Although the Court acknowledged that parodies are inherently expressive, it held that when an alleged infringer uses a trademark as a designation of source for the infringer's own goods, the Rogers test does not apply (though, the Court acknowledged that even if Rogers was inapplicable, VIP Product’s parodic efforts might be relevant in a standard trademark analysis).

The Second Circuit held that “MSCHF used Vans' marks in much the same way that VIP Products used Jack Daniel's marks — as source identifiers” and highlighted several ways that MSCHF’s design evoked elements of trademarks and trade dress from Vans’ Old Skool shoes, including the classic black and white color scheme, the side stripe, the perforated soles, the logo on the heel and footbed, and the packaging. The court therefore concluded that MSCHF used these elements as designation of source and, relying on the SCOTUS opinion, that MSCHF was not entitled to the heightened review under the Rogers test. The court clarified, “even if a defendant uses a mark to parody the trademark holder’s product, Rogers does not apply if the mark is used ‘at least in part for source identification.’” In other words, Vans would have been well within its rights to pour a celebratory shot of Jack as MSCHF’s most prominent defense had been rejected on appeal.

After determining that the district court did not err in declining to apply the Rogers test, the Second Circuit had the task of deciding whether the district court erred in its traditional consumer confusion analysis. The likelihood of confusion test involves a balancing test of eight factors, which the Second Circuit used to affirm the lower court’s finding that Vans was likely to prevail on the merits of its infringement claim.

The Second Circuit was ultimately unimpressed by MSCHF’s mischief and kicked off its main defenses. More broadly, this case serves as an example of how the Supreme Court’s Jack Daniel’s precedent affects the Rogers analysis in other types of fact patterns and disputes. With MSCHF blocked from selling any additional Wavy Baby’s, sneakerheads and art collectors looking for "wobbly, and unbalanced” skate shoe artworks (along with the accompanying MSCHF manifesto on consumer culture) will have to check the secondary markets.

In the meantime, the court docket in the case shows that, as of a March 2024 telephone conference with the court, the parties are exploring a possible settlement – especially since MSCHF’s petition to the Supreme Court requesting review the Second Circuit’s decision was denied on procedural grounds.

Dr. Thomas House (“House”) – ex-Major League Baseball pitcher, coach and sports psychology Ph.D. – dealt a strikeout to Player’s Dugout, Inc. (“PDI”) after the Sixth Circuit affirmed most of his $450,000 award for PDI’s trademark infringement in favor of House’s pitching training company, National Pitching Association, Inc. (“NPA”). (House v. Player’s Dugout, Inc., No. 22-5843 (6th Cir. Feb. 8, 2024) (unpublished)).

House created the NPA in 2002, offering both training for young athletes and baseball coach certification clinics. Drawing on his pitching background, coaching experience and research on biomechanics, House developed an arm care program for baseball players called the Personally Adaptive Joint Threshold Training Program (“PAJJT Program”), which included a personalized weighted-ball program. In 2003, PDI founder Joe Newton met House and Jamie Evans, a part owner of NPA, and learned about the PAJJT program. Fast forward to 2010 and Newton began implementing a weighted-ball program at PDI with Evans’ help under the name “Velocity Plus Arm Care Program” (“Velocity Plus program”). Concerned that his idea was being picked off, House entered into a license agreement with PDI to use and commercialize the PAJTT program (under the Velocity Plus name) on an exclusive basis in exchange for per-participant royalties. House also agreed to notify PDI if he became aware of any unlicensed use of the Velocity Plus program and to take steps to prevent such use.

PDI began advertising its association with NPA and House, using the NPA trademark, the phrase “Powered by Tom House,” and a picture of Newton and House together on the PDI website. House also began promoting his association with PDI to all coaches in the NPA network, which spurred more coaches to sign up for the Velocity Plus program.

Unfortunately, the relationship that looked like a home run soon faded at the warning track. PDI believed that House was ineffective at blocking pirated third-party pitching programs and House thought PDI was not following proper PAJTT protocol in its programming. PDI then stopped making royalty payments in September 2015, prompting NPA to send a letter to PDI requesting the parties terminate the License Agreement. NPA also sent a letter to its network of certified coaches notifying them of such termination on the grounds that PDI was not following certain program protocols. Finally, House officially notified PDI in February 2016 that it was in breach of contract for failing to pay royalties and thereafter terminated the contract in June 2016 and demanded that PDI cease and desist from using House’s name and NPA’s marks.

In September 2016, House took the mound against PDI in Kentucky federal district court, showcasing a repertoire of pitches, including breach of contract, federal trademark infringement and federal unfair competition claims, and seeking compensatory and punitive damages. PDI sought to foul off House’s claims and counterclaimed alleging breach of contract, defamation and unfair competition claims of its own. In November 2021, the matter went to trial and the jury reached a split verdict awarding $450,000 in damages in favor of NPA for breach of contract and trademark infringement (which included $67,649.82 in punitive damages), and an award to PDI of $200,000 for defamation and tortious interference.

The trial court rejected the defendant’s post-trial motion for a renewed judgment as a matter of law and awarded attorney’s fees to both parties (House was awarded fees as the “prevailing party” on his Lanham Act claims; PDI was awarded partial fees for prevailing on its unfair competition counterclaim). The Sixth Circuit affirmed most of the award but ruled, among other things, that NPA’s punitive damage award must be reconsidered under the correct legal standard of “clear and convincing evidence.” The court’s decision in this case may help future judges determine the strike zone for damage instructions in trademark cases.

The Sixth Circuit considered a number of arguments on appeal, but the two main issues were: 1) whether the jury’s award of $340,000 in lost profits under the Lanham Act was excessive because the damages were not attributable to the use of NPA’s trademark and House’s name; and 2) whether the district court erred in citing a “preponderance of the evidence” standard for punitive damages in its jury instruction, instead of the “clear and convincing evidence standard.”

As the Sixth Circuit stated, a plaintiff seeking lost profit damages under the Lanham Act must “show some connection between the identified ‘sales’ and the alleged infringement.” To successfully recover, the plaintiff must generally prove how much of the defendant’s sales (not profit) were earned from using the trademark during the alleged infringing period and show that there is some causal connection between the identified sales and the alleged infringement. Then, the burden shifts to the defendant to establish their actual profit (noting costs and deductions). Essentially, this approach assumes that the defendant’s profits equal his gross sales unless he presents evidence otherwise.

The appeals court affirmed that NPA established a sufficient connection between the Velocity Plus program and NPA’s marks, because “PDI used the NPA and House’s name and experience to promote the Velocity Plus program…[and] display[ed] the NPA mark and House’s photo and information on its website…[and] each sale of the Velocity Plus program included a kit containing various weighted balls, each of which bore the NPA trademark.” Thus, after considering PDI’s costs, the court affirmed the award of $340,000 in lost profits for House.

While PDI’s lost profits argument was left on base, it did score when arguing against the $67,649.82 state law punitive damages award for unfair competition. Specifically, the Court found that Kentucky law clearly establishes a “clear and convincing evidence” standard for an award of punitive damages, yet the district court instructed the jury to grant punitive damages under a “preponderance of the evidence” standard. This mistake amounted to “plain error” by the district court and impacted PDI’s substantial rights and the jury’s consideration of damage.

Given the split jury verdict, the Sixth Circuit’s mixed ruling was not surprising, giving PDI one more chance to scrape out a hit while down in the count. In the meantime, on March 4, 2024, PDI requested replay review of the Sixth Circuit’s decision, seeking a panel rehearing, which was denied on April 2, 2024, thus sending the case back to the district court to sort out the remaining issues.

On December 31, 2023, the daily fantasy sports site, SidePrize LLC d/b/a PrizePicks (“PrizePicks”) agreed to pay almost $15 million to settle New York State Gaming Commission (the “NYSGC”) allegations that PrizePicks made interactive fantasy sports (“IFS”, also known as “daily fantasy sports” or “DFS”) offerings available to New York residents without being a registered IFS operator under Article 14 of the NY Racing, Pari-Mutuel Wagering and Breeding Law (the “Racing Law”). (New York State Gaming Commission Stipulation of Settlement, NYSGC Case No.: PRPI-IFS-001-2023 (Dec. 31, 2023)) (the “Settlement”). According to the Settlement, PrizePicks alleged that it believed in good faith that it was authorized to operate IFS in New York (perhaps because it offered a slightly different style of gaming than licensed fantasy sports platforms), but ultimately accepted its loss and settled-up with the NYSGC.

PrizePicks is a daily fantasy sports site that offers a variety of DFS games depending on the state law under which it operates. PrizePicks was apparently not an authorized IFS operator in New York, so in the NYSGC’s view, it was not permitted to offer any IFS games in New York. One DFS game offered by PrizePicks, called Pick ‘Em, attracted the attention of regulators. Pick ‘Em differs from usual daily fantasy sports offerings. In traditional daily fantasy sports games a user creates a lineup of players within a certain budget and earns points based on those players’ performances in that night’s sports games, with users playing against each other for a share of a pre-determined pot collected from entry fees. Instead of playing peer-to-peer against other players, PrizePicks’s Pick’ Em games were a parlay-style bet against the house, and instead of drafting a team of players and earning points based on their collective performance in real sporting games, these games were more akin to proposition (or “prop”) bets more commonly offered at sportsbooks where bettors, for example, might place wagers on certain occurrences during a game or different sporting events (e.g., Player X scores over 25 points and Pitcher Y will have less than 10 strikeouts). In its Pick ’Em style DFS games, PrizePicks offers players a chance to parlay a minimum slate of prop-style over/under bets together – the more prop bets linked together (up to a certain maximum), the odds of winning go down, but the payout goes up. Certain licensed New York sportsbooks reportedly lobbied officials to clarify state IFS regulations, contending that Pick ‘Em-style games were essentially unlicensed “sports betting” activity and New York regulators agreed.

In October 2023, over opposition from PrizePicks and similar DFS operators, New York regulators approved new regulations governing IFS contests, including a ban on fantasy games that have similar characteristics to sportsbook-style prop bets: “Contests shall not be based on proposition betting or contests that have the effect of mimicking proposition betting. Contests in which a contestant must choose, directly or indirectly, whether an individual athlete or a single team will surpass an identified statistical achievement, such as points scored, are prohibited.” Prior regulations already stated that operators must “ensure no winning outcome shall be based on the score, point spread, or performance of a single sports team, or any combination of such teams” and “ensure no winning outcome shall be based solely on any single performance of an individual athlete in a single sport or athletic event.” (Racing Law, Article 14, §§1404(1)(q) & (r)).

With Pick ‘Em-style daily fantasy games clearly within the sights of the NYSGC (and other state regulators), the odds of enforcement against operators like PrizePicks went up, particularly since PrizePicks was operating what was purportedly a daily fantasy sports site in New York without an IFS permit since June 2019. On November 22, 2022, the NYSGC issued a Subpoena Duces Tecum to PrizePicks to investigate the operation of its website and mobile apps. The NYSGC has the authority and responsibility to “monitor any corporation, association or person engaged in gaming activity for compliance with” and “conduct investigations and hearings pertaining to violations of” the Racing Law. (Racing Law, Article 1, §§104(4) & (6)). NYSGC also has the authority to impose civil penalties. Most relevant to this action, under Racing Law §§1402(1)(a) & 1412, no operator shall “administer, manage, or otherwise make available” an IFS platform to state residents unless registered with the NYSGC.

As stipulated in the settlement, the losing bets stacked up for PrizePicks, including that: PrizePicks operated an IFS site and app within the meaning of Racing Law Article 14, made its offerings available to New York residents and neither held a temporary permit nor an authorized registration from the NYSGC to operate IFS in New York. While PrizePicks’ Pick ‘Em-style games may have been what attracted the scrutiny of the NYSGC, the Settlement merely states that PrizePicks was simply not authorized to offer any daily fantasy games in New York but had nevertheless been offering IFS in New York since June 4, 2019.

The NYSGC fined PrizePicks $14,969,688, which was based on, among other things, the revenue (or "rake”) that PrizePicks generated in commissions for operating IFS contests in New York for the period of June 4, 2019 through November 3, 2023. Under the settlement, PrizePicks also agreed to cease and desist “any operations and offerings in New York that PrizePicks characterizes as IFS” by February 14, 2024 and to provide proof to the NYSGC of such cessation.

It’s not necessarily game over for PrizePicks in New York. The NYSGC recognized that PrizePicks cooperated with it throughout the investigation and that none of PrizePicks’s actions disqualified it from applying for an IFS registration. PrizePicks noted that it is currently working with the NYSGC to get approval and a license for its peer-to-peer product and as a hedge, will continue to offer a free-to-play version in New York state. Still, scanning the headlines, it appears the prospect for PrizePicks’s prop bets-style action in other states is similarly dimming. Regulators in other states, such as Massachusetts, Wyoming and Maryland, have brought their own actions to shut down PrizePicks’s prop-style betting games, and other states may be likely to follow in bringing enforcement actions or tightening DFS regulations.

On March 19, 2024, the Football Governance Bill (the “Bill”) was introduced in Parliament. The Bill seeks to establish a new “Independent Football Regulator” (the “IFR”) to oversee clubs in England’s top five men’s football leagues.

Under the proposals in the Bill, the IFR would be a standalone body independent of both Government and football authorities. Its core objectives are threefold: (1) to improve financial sustainability of clubs, (2) to ensure financial resilience across the leagues, and (3) to safeguard the heritage of English football. In order to achieve these goals, the IFR would have several rights and responsibilities, including the following:

- Licensing System:The IFR would implement a licensing system whereby clubs would need a licence to operate. The proposed regime would involve both provisional and full licences to give clubs time to transition. The provisional licence, which would run for a maximum period of three years unless extended by the IFR and would require clubs to meet certain baseline conditions. Thereafter, the IFR would apply additional bespoke licence conditions on clubs, as necessary and proportionate to a club’s specific circumstances, to ensure they meet the required standards for a full licence across three key areas: (1) financial resources, (2) non-financial resources (e.g., relevant systems, policies and personnel), and (3) fan engagement (e.g., clubs must consult their fans on key off-field decisions). Non-compliance with the licensing system’s standards could result in the IFR withdrawing a club’s licence and inflicting financial penalties on the club.

- Backstop Powers re: Financial Distributions:The IFR would have backstop powers to intervene in financial distributions among the leagues. This authority is a direct response to the ongoing row over financial distributions between the Premier League and the English Football League – if the leagues fail to agree on a fair deal, the IFR could invoke its powers to ensure a settlement is reached.

- Owners’ and Directors’ Test: The IFR would establish strengthened owners’ and directors’ tests to ensure clubs don’t fall into the wrong hands. With respect to new owners and directors, the IFR would examine the suitability of such individuals before they are allowed to assume their roles. Such assessment would involve (1) a traditional review of integrity, honesty, financial soundness, and competence, (2) enhanced due diligence of the source of the applicable individual’s money; and (3) submission of a business plan that illustrates how such individual would run the applicable club sustainably. The IFR would apply similar tests to existing owners and directors and would have the power to remove such individuals (including by forced divestment) if they are found to be unsuitable.

- Breakaway Competitions and Relocations:In order to avoid fan outrage and protect the heritage of football, the IFR would have the power to block clubs from competing in unapproved breakaway competitions and must pre-approve any proposed relocation from a club’s home ground.

Although many specifics of the IFR’s framework remain to be determined, the Government has established a shadow regulator that will operate while the Bill makes its way through Parliament and the IFR is formally established. The shadow regulator is currently undertaking preparatory activity for the IFR, including (a) designing an organization with the appropriate governance and expertise, (b) engaging clubs in early discussions about the operation and implementation of the regime, and (c) working with football authorities on sharing information and existing best practices within the industry.

In order to become law, the Bill must be approved by each House of Parliament and receive the Royal Assent. Now that the Bill has been introduced, the Bill will next be debated at the Second Reading in the House of Commons, the date of which has not yet been announced. All interest parties should closely monitor the progress of the Bill.