Asserts Affirmative Defenses and Antitrust Counterclaims and Asks for Declaratory Judgment

On Monday Ambry filed its Answer to Myriad's complaint for patent infringement, and asserted patent misuse as an affirmative defense. Ambry also asked the District Court for a declaratory judgment of non-infringement and invalidity of all patents Myriad has asserted, and raised antitrust counterclaims under the Sherman and Clayton Acts.

On Monday Ambry filed its Answer to Myriad's complaint for patent infringement, and asserted patent misuse as an affirmative defense. Ambry also asked the District Court for a declaratory judgment of non-infringement and invalidity of all patents Myriad has asserted, and raised antitrust counterclaims under the Sherman and Clayton Acts.

Procedurally, Ambry raised no challenge to jurisdiction or venue, but denied that the named plaintiffs are the owners or co-owners of the asserted patents, and admitted only that it provides genetic diagnostic testing services including for its BRCAplus, Breastnext, CancerNext, and OvaNext tests as of June 13, 2013.

Substantively, Ambry's Answer denies that any of the patents were duly and legally issued, that the claims are valid or infringed, or that Myriad has suffered any damages. Ambry contends as affirmative defenses that Myriad fails to state a claim for relief, and that the patents are invalid under §§ 102, 103, 112, that the asserted claims do not recite patent-eligible subject matter under § 101, and that Myriad's asserted claims are unenforceable under the doctrine of patent misuse. The Answer asserts no factual or legal grounds for any of its affirmative defenses.

It is in Ambry's counterclaims that things get interesting. Ambry asserts that it is "a CAP-accredited, CLIA-certified commercial clinical laboratory, a recognized leader in diagnostic and contract genomic services specializing in the application of new technologies to molecular diagnostics and genetics research." Its counterclaims are based on Sections 4 and 16 of the Clayton Act, 15 U.S.C. §§ 15 and 26, and seek treble damages and injunctive relief under the Sherman Act, 15 U.S.C. § 2. Ambry also seeks a declaratory judgment that all claims of the patents asserted by Myriad are invalid and not infringed, either directly or through inducement (presumably, under 35 U.S.C. § 271(b)). There are no allegations of unenforceability for inequitable conduct.

In its background facts, Ambry asserts the following allegations:

• Myriad is maintaining its monopoly in violation of the antitrust laws through "bad faith" enforcement of its patents

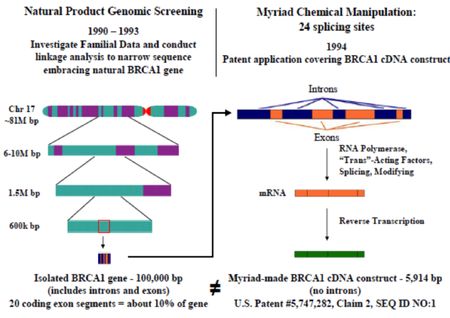

These assertions are based on Ambry's allegations that Myriad "knows" its patents are invalid under the Supreme Court's AMP v. Myriad and Mayo v. Prometheus decisions and the Federal Circuit's Myriad decision regarding method claims not asserted in this litigation. Ambry characterizes this litigation as a continuation of "sharp and overreaching practices to wrongfully monopolize the diagnostic testing of human BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes in the United States and to attempt to injure any competitor who dares to challenge Myriad's monopoly." These "sharp" practices include "(1) using research funded by public money to file patents over alleged inventions that the Supreme Court and the Federal Circuit have confirmed never should have been patented [an ex post facto argument that ignores the University of Utah's obligations to file such patents under the Bayh-Dole Act], (2) using those patents to intimidate and chill competition in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genetic screening markets in the late 1990s to ensure monopoly profits, (3) taking patients' personal BRCA1 and BRCA2 genetic sequence data and depriving the public of access to that data to inhibit competition, and (4) using sales and marketing tactics with genetic counselors and payors to intentionally misrepresent the accuracy and reimbursement of Ambry's BRCA1 and BRCA2 diagnostic tests." In Ambry's telling of the tale, the Utah inventors benefited from international efforts to identify breast cancer-specific genes, including identification of chromosome 17 as the site of BRCA1 by Mary Claire King. This, in Ambry's telling, was the critical observation, after which "standard and well-known techniques could be used to sequence the gene." This reading minimizes the vast difference between identifying a chromosome, or even a chromosomal region, genetically linked to a disease or disorder and isolating and sequencing the gene, as illustrated below (graphic courtesy of Courtenay Brinckerhoff):

The situation with the BRCA2 gene was similar, according to Ambry, with the Stratton group identifying chromosome 13 as the locus of that gene, and the collaborative nature of work towards its identification. In addition, Ambry asserts that the Stratton group also isolated and sequenced BRCA2, at about the same time that Myriad announced its isolation of the gene. Ambry also emphasizes the amount of "public and private" grant monies received by the Skolnick group ("$5 million in 1992, $8 million in 1993, and $9 million in 1994"), and later in their complaint alleges that Myriad attempted to deprive NIH researchers credit for inventorship (later rectified) and royalties (allegedly still owed these inventors).

The situation with the BRCA2 gene was similar, according to Ambry, with the Stratton group identifying chromosome 13 as the locus of that gene, and the collaborative nature of work towards its identification. In addition, Ambry asserts that the Stratton group also isolated and sequenced BRCA2, at about the same time that Myriad announced its isolation of the gene. Ambry also emphasizes the amount of "public and private" grant monies received by the Skolnick group ("$5 million in 1992, $8 million in 1993, and $9 million in 1994"), and later in their complaint alleges that Myriad attempted to deprive NIH researchers credit for inventorship (later rectified) and royalties (allegedly still owed these inventors).

Following these events, Ambry asserts that Myriad "quickly set out to commercialize its discoveries," inter alia, by applying for patents on the isolated BRCA1 and BCRA2 genes. According to Ambry:

These patents rest on patenting the isolated DNA sequence of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes. The claims at issue in this case do not cover novel diagnostic tools or methods used in genetic testing. Nor are they analogous to patents on novel medical instruments. Rather, these claims attempt to confer upon Myriad the exclusive right to read human BRCA1 and BRCA2 sequences.

(As in the ALCU's lawsuit, Ambry reduces the actual methods used to determine a genetic sequence to merely "reading" a sequence.) Departing from factual allegations, Ambry proceeds to argue that Myriad's claims "either attempt to assert broad ownership over all human DNA sequences that can be used to amplify and sequence BRCA1 and BRCA2, or merely append routine steps to the patent claims, which would necessarily be conducted while assessing the biological relationships between mutations in the BRCA1 and or BRCA2 genes and the predisposition to cancer." Further, Myriad's patenting strategy "is an overt attempt to convert these natural biological phenomena into patentable inventions using the patent language of a 'method' or 'process.'" "In other words, the patent claims are directed to routine biological procedures and correlations generically such that it is effectively impossible for anyone in the United States in any meaningful way to 'make' or 'use' natural forms of isolated DNA molecules encoding the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes in humans without infringing Myriad's patents," features that, in Ambry's view should apply to any genetic diagnostic method and, indeed, almost all diagnostic method claims.

Returning to its characterization of the facts, Ambry asserts that Myriad "set up $30 million diagnostics laboratory" and provided three tests: a comprehensive assessment of both BRCA1 and BRCA 2 (costing $2400); a "single site" test for mutations "previously identified in another family member" ($395); and a "multisite" test specific for members of the Ashkenazi Jewish population. Ambry also sets out Myriad's efforts to assemble "a group of laboratories, health insurers, sales teams and doctors to market and sell its tests," resulting in $20 million in revenue in the first three quarters of 1997 alone. At the same time, according to Ambry, Myriad was threatening competitors (including those at the Genetic Diagnostic Testing Laboratory at the University of Pennsylvania) with infringement lawsuits for offering BRCA gene testing, and filed such a lawsuit against the University, which settled with an agreement that university laboratories would not offer these tests. Interestingly, Ambry's allegations of Myriad's malfeasance include a settlement of litigation between Myriad and OncorMed that resulted in Myriad acquiring OncorMed's patents "to extend its monopoly."

• Myriad eschews considerations of affordability, test accuracy and recommendations for genetic testing

These allegations are based on the following facts according to Ambry. Compared with OncorMed, Myriad offered a comprehensive rather than a "tiered" approach to testing, thus requiring the $2400 test rather than tests of fewer mutations offered by OncorMed costing around $500. (Of course, when testing a "naïve" patient, i.e., one whose family history with regard to the existence of BCRA gene mutations was unknown, Myriad's testing would provide the best information on whether the patient was at risk for inherited breast cancer.) Ambry also notes that while OncorMed complied with recommendations of a Federal Task Force on Genetic Testing (issued March 1996, at the dawn of the generic testing era), Myriad did (and does) not. (A similar situation exists for recommendation from the American Society of Clinical Oncologists, issued May, 1996.) Also in this section of the complaint are allegations that Myriad "misses" "up to 12%" of certain types of genetic variations (specifically, rearrangements, deletions and insertions), citing Congressional testimony from interested parties (including Wendy Chung, one of the ALCU plaintiffs) attributing delays in this testing to Myriad's "monopoly."

• There exists significant opposition to Myriad's business model of patenting gene sequences and establishing a private database

This portion of Ambry's counterclaims highlights Myriad's decision in 2004 not to contribute additional information on BRCA gene mutations obtained through is testing to a public repository of breast cancer-specific mutations, and the reaction of "[p]oliticians, clinicians, breast cancer advocacy groups and commentators" who oppose this decision (including the "Sharing Clinical Reports Project"). Also mentioned is the ACLU's lawsuit and the Supreme Court's decision invalidating five of nine claims at issue before the Court.

• Myriad is aware that its asserted claims on BCRA1 and BCRA2 genes are invalid under recent Supreme Court and Federal Circuit cases

In this portion of the "factual" background for its counterclaims, Ambry recites the history and outcomes of the ACLU's Myriad litigation, from the District Court through the Supreme Court's June 13th decision, as well as the effects of the Court's Mayo decision on this lawsuit. (The history of these lawsuits have been extensively discussed and Ambry's characterization thereof will not be set forth here.) This history is recited here as evidence that "rebuts and presumption [that] Myriad [] brought this suit in good faith."

As a consequence of these litigations, Ambry contends that "[Myriad's] asserted composition claims are not patent eligible, because they are identical to sequences that occur in nature (a variation of the Department of Justice's "magic microscope" test not explicitly relied upon by the Court). According to Ambry, Myriad's asserted claims reciting BRCA gene-specific primers "on their faces fail to recite patentable subject matter" because the Supreme Court in its Myriad decision "unequivocally excluded from patentable subject matter synthetic DNA 'that may be indistinguishable from natural DNA.'" (This is probably Ambry's strongest argument.) Merely being "synthetic" is not enough to render these primers patent eligible, according to Ambry: "even though the probe or the primer may have been synthesized in a laboratory, [it is not patent eligible] so long as it mirrors, in whole or in part, the genomic DNA of the BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes."

Turning to Myriad's asserted method claims, Ambry's argument is on less firm ground. According to Ambry, these claims are also invalid under Myriad (and Mayo) because they recite "two biochemical processes [that] were well known in the art." However, what was "routine, well-understood and conventional" in Mayo was not just the type of methods applied in those claims but the actual application of the recited methods themselves (i.e., testing blood from patients administered 6-thioguanine to determine drug or metabolite levels). Here, in contrast, Ambry's argument is that these "two biochemical processes" (amplifying and sequencing DNA) were generically known, which it true. But the application of these methods to the BCRA genes was not "routine, well-understood and conventional" prior to Myriad's patent filing because the subject matter, the BRCA genes, were unknown in the art. Ambry attempts to overcome this logical deficiency by equating the BRCA genes to be a "law of nature"; while the association of specific mutations with breast cancer may be such a law, the genes themselves are not. In keeping with the doctrinal laxness of the Court's Mayo decision, Ambry's arguments in this regard include not only subject matter ineligibility but the purported lack of novelty and obviousness of Myriad's methods, ignoring the fact that none of these deficiencies applies to the knowledge of the BCRA genes' existence in the prior art. Indeed, it is much more consistent with the Supreme Court's Myriad decision that such claims are patent-eligible, in view of the Court's statement that:

Similarly, this case does not involve patents on new applications of knowledge about the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes. Judge Bryson aptly noted that, "[a]s the first party with knowledge of the [BRCA1 and BRCA2] sequences, Myriad was in an excellent position to claim applications of that knowledge. Many of its unchallenged claims are limited to such applications."

Regardless, Ambry contends that Myriad filed its lawsuit "to enforce its invalid patents in bad faith in order to keep competitors from entering the market," citing Myriad's intention to maintain the "status quo" (which, according to Ambry is Myriad's "wrongful monopoly") as set forth in its brief in support of its preliminary injunction motion. Ambry also asserts as an improper motive for the lawsuit its intention to contribute the results of its BRCA gene testing to public databases. In Ambry's view, Myriad's failure to do the same constitutes an attempt to use "its invalid patents to maintain as secret patients' gene sequences (which do not belong to Myriad) in an attempt to limit competition." And Ambry also asserts that Myriad is using the lawsuit to delay market entry by competitors other than Ambry, and to incorporate aspects of its own technology into Myriad's testing, resulting in an expropriation of "Ambry's superior screening services, which utilize more sensitive, efficient and cost-effective next-generation sequencing technologies."

Finally in this portion of Ambry's counterclaims is the allegation that Myriad has "market power" and that its activities have harmed the market. This portion of Ambry's counterclaims assert that the market is diagnostic genetic testing for BCRA gene mutations in the United States, for which "[t]here are no products that are reasonably interchangeable substitutes for [BRCA] genetic tests." BRCA testing is also subject to high barriers to entry, including "the various patents Myriad holds, the technological know-how for designing and running genetic tests to identify mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2, and establishing relationships with genetic counselors and hospitals, many of which are already heavily utilizing Myriad's tests." Myriad has an "over 90% market share" for BRCA genetic testing and "possesses the power to control prices and exclude competitors." And the public suffers because Myriad's tests are "nearly 100% higher" in costs than Ambry's. Additionally, Ambry contends that Myriad's contention that Ambry's testing has "variant of unknown significance (VUS)" rates of 10-30% are false, and that Myriad knowing this falsity has had its employees conduct a campaign of informing genetic counselors of this false VUS rate for Ambry's BRCA testing. And these allegations (which are used to support Ambry's antitrust counterclaims) extend past Myriad: "Plaintiffs in this action are aware of the anticompetitive and exclusionary conduct by Myriad [and] that each and every Plaintiff is aware that the claims of the asserted patents are facially invalid [and] that each and every plaintiff was involved in the decision to bring this lawsuit, notwithstanding that the asserted claims are facially invalid."

Count 1 of Ambry's counterclaims is brought under Section 2 of the Sherman Antitrust Act (against Myriad only). According to this counterclaim:

126. Myriad is willfully maintaining its monopoly through exclusionary conduct as distinguished from growth or development as a consequence of a superior product, business acumen, or historic accident. Myriad seeks to maintain its monopoly position through various anticompetitive conducts described above, including through the bad faith enforcement of its facially invalid patents.

127. Myriad was aware before filing its Complaint in this action that the claims it was asserting are invalid per Myriad and Prometheus.

128. Through its exclusionary and anticompetitive conduct, Myriad has acquired and maintained its monopoly in the relevant market for genetic testing for patients seeking analysis of their full BRCA1 and BRCA2 gene sequences. Myriad has operated in this manner free from competition because of the high barriers to entry that exist in the market, including Myriad's invalid patents, the technological know-how to design and run genetic tests, and the actions of Myriad's employees.

Ambry alleges it has suffered "substantial injury to its business and property" as a consequence, and that "[c]ompetition in the relevant market" has similarly suffered "[d]ue to Myriad's anticompetitive conduct."

Count 2 is brought under the Sherman Act for "attempted" monopolization for substantially the same market behavior, Ambry alleging that Myriad acted "with a specific intent to monopolize the relevant market through the assertion of facially invalid patent claims and the anticompetitive conduct of its employees."

Ambry does not expressly assert that the patents were obtained through fraud, or that the litigation is brought as a sham, but rather that the effects of Myriad's assertion of patent claims Ambry asserts are invalid under recent Federal Circuit or Supreme Court precedent should incur antitrust liability. In this regard no better authority that Chief Justice Roberts may be consulted regarding the relevant legal standard:

The point of patent law is to grant limited monopolies as a way of encouraging innovation. Thus, a patent grants "the right to exclude others from profiting by the patented invention." Dawson Chemical Co. v. Rohm & Haas Co., 448 U. S. 176, 215 (1980). In doing so it provides an exception to antitrust law, and the scope of the patent -- i.e., the rights conferred by the patent -- forms the zone within which the patent holder may operate without facing antitrust liability.

This should go without saying, in part because we've said it so many times. Walker Process Equipment, Inc. v. Food Machinery & Chemical Corp., 382 U. S. 172, 177 (1965) ("'A patent . . . is an exception to the general rule against monopolies'"); United States v. Line Material Co., 333 U. S. 287, 300 (1948) ("[T]he precise terms of the grant define the limits of a patentee's monopoly and the area in which the patentee is freed from competition"); United States v. General Elec. Co., 272 U. S. 476, 485 (1926) ("It is only when . . . [the patentee] steps out of the scope of his patent rights" that he comes within the operation of the Sherman Act); Simpson v. Union Oil Co. of Cal., 377 U. S. 13, 24 (1964) (similar).

The key, of course, is that the patent holder -- when doing anything, including settling -- must act within the scope of the patent. If its actions go beyond the monopoly powers conferred by the patent, we have held that such actions are subject to antitrust scrutiny. See, e.g., United States v. Singer Mfg. Co., 374 U. S. 174, 196–197 (1963). If its actions are within the scope of the patent, they are not subject to antitrust scrutiny, with two exceptions concededly not applicable here: (1) when the parties settle sham litigation, cf. Professional Real Estate Investors, Inc. v. Columbia Pictures Industries, Inc., 508 U. S. 49, 60–61 (1993); and (2) when the litigation involves a patent obtained through fraud on the Patent and Trademark Office. Walker Process Equipment, supra, at 177.

FTC v. Activis (Roberts, CJ, dissenting).

The other asserted counterclaims comprise asking the Court for a declaratory judgment of non-infringement and invalidity of each of the asserted patents.

Ambry asks for a jury trial, declaratory judgment, an injunction under Section 16 of the Clayton Act to prevent Myriad or the other plaintiffs from enforcing the patents-in-suit, treble damages on Ambry's Sherman Act antitrust counterclaims, and costs and attorneys' fees.