After a brief time when it seemed that Americans were coming together in favor of social isolation to slow the spread of the novel coronavirus, it seems that our response is now getting more polarized by the day. As the President tweets to “liberate” Wisconsin, Michigan, and Virginia, protestors, sometimes armed, are massing at state capitals and governors’ residences to call for an end to the lockdowns. In taking that position, it seems that a substantial minority of Americans are rejecting the advice of scientists and public policy experts who are saying that the best way to limit the deaths and to protect the economy in the long-run is to continue to limit social contact until widespread testing and contact tracing can catch up.

In the next couple of weeks, as states work through the difficult decisions on when and how to re-open economic activity, we can expect that gap to widen. The coronavirus response is becoming yet another scientific battlefield, similar to what has happened with vaccines and the climate. In the process, the question of what someone thinks about science continues to become more polarized and partisan. It isn’t just a matter of education or comprehension; it is a matter of motivated cognition driving the question of whether we should trust scientists or not. Whether science matters is also something that can matter when jurors are evaluating scientific evidence in court. In this post, I will take a look at some of the research, and share some thoughts on presenting science to an audience that might possess a motivated skepticism.

The Partisan Science Split

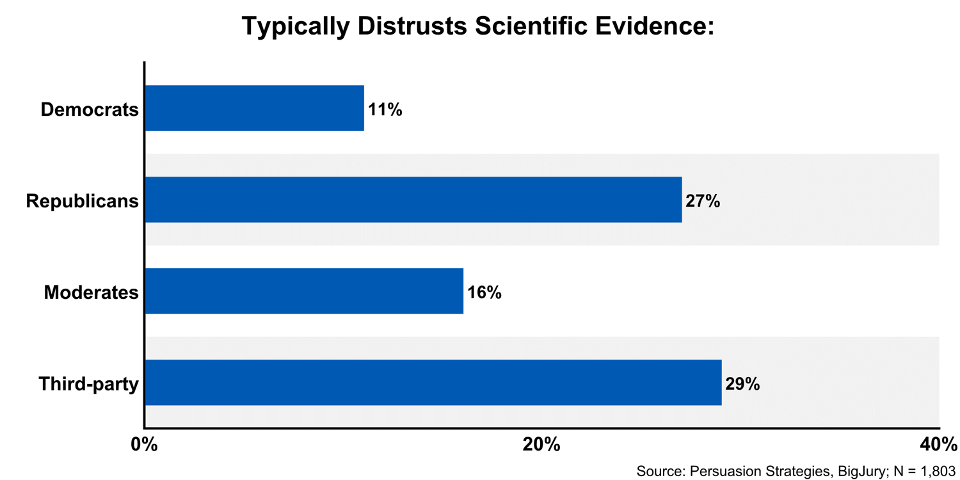

Using our own data, Persuasion Strategies has studied the partisan divide in attitudes toward science. In data collected over the past two years, for example, we observed a much stronger tendency among Republican voters to distrust science.

This data was collected before the coronavirus controversy, but data collected just this month from the National Bureau of Economic Research (Allcott et al., 2020) shows that this greater distrust among conservatives extends to coronavirus precautions. They note significant differences in behavior regarding personal distancing, as well as beliefs about the future of the pandemic. While these differences, to some extent, stem from the fact that Democrats are more likely to live in the denser populated urban areas that are harder hit (so far), the researchers note that even after controlling for population densities, actual infection rates and deaths, as well as state policies, there are still significant differences between Republicans and Democrats, with the former group being more skeptical of the threat.

Part of this response could come down to a belief that downplaying the coronavirus pandemic is implicitly a means of supporting their party’s president, and the belief that a faster re-opening of the economy aids in his reelection. But part of that is also a distrust of science generally that conservatives have learned and applied on other issues. For example, it is noteworthy that the anti-lockdown protests have also attracted those who are also opposed to vaccines, along with other conspiracy thinkers.

The Climate Precedent

The Takeaway radio show recently aired a segment discussing research showing that climate skepticism paved the way for the current coronavirus skepticism. Speaking with Jerry Taylor, President of the bipartisan think tank Niskanen Center, and Amy Westervelt, Editor in Chief of Drilled News, the discussion focused on a number of the common facets of science denial that have been applied in various contexts. Thinking that science is not objective, but is instead alarmist and driven by elites with special interests, is a mindset that has easily crossed the bridge from climate to COVID-19. They also noted, “Recent data shows that places where people are less likely to agree climate change is happening are also the places where people haven’t changed their behaviors as much in response to coronavirus.”

The Response

Often litigators need jurors to be able to listen to scientific experts and to keep an open mind when listening to scientific testimony. In these times, we cannot take it for granted that the common trappings of scientific credibility — credentials, experience, systematic investigation — are going to be persuasive to all. In addition to asking about scientific views in voir dire, it is also important to shape your message and your testimony so it answers some of the main questions that skeptics are likely to have. `

Knowledge or Status?

Science skeptics sometimes nurse the narrative that the scientific conclusions being offered are not so much the product of specific knowledge, but are instead the product of the source’s position or “elite” status. So, the common advice to expert witnesses of “Show your work,” becomes all the more important in an age of scientific skepticism. You need to be clear enough that your jurors can reason their own way to your conclusions.

Consensus or Conspiracy?

Those supporting the science on some issues, like climate, vaccines, or the coronavirus, are often frustrated by the need to defend their conclusions. The argument that “this is the scientific consensus, it should not be in dispute,” however, can fall on deaf ears. The fact of a consensus can end up just looking like a conspiracy: Even if all the elites are on one side, that doesn’t make them correct. So rely on the reasoning behind the claim, more than you rely on its degree of support.

A Full Harvest or Cherry-Picking?

When faced with a fact that can’t be denied, a skeptic can still feel like you are selectively cherry-picking rather than sharing the full scope of information. For that reason, it is important to prove that you are not hiding anything. In testimony, there will always be challenges based on the allowable scope of testimony, but when it is possible to show that you aren’t holding anything back (for example, by sharing something that, in a small way, helps the other side) that adds to your credibility.

Ultimately, the choice of beliefs for or against science often comes down to motivated cognition: We find ways to believe what we want. So, when preparing your case or your testimony, it helps to ask not just “What will prove my position?” but also “What will make them want to believe that proof?” That means focusing on interests. So someone who is now de-emphasizing the health risks of coronavirus because they understandably want to get back to work could be hit with this argument: If we do too much too soon, the resulting re-quarantine will mean the economy is going to take even longer to recover.

____________________

Image credit: Lorie Shaull, Flickr Creative Commons (photo taken at “Liberate Minnesota” protest at governor’s mansion, April 17).