October 14th was a busy day at the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) for the current interference over CRISPR technology (No. 106,115). The Junior Party (the University of California, Berkeley; the University of Vienna; and Emmanuelle Charpentier; collectively, "CVC") filed its Substantive Motion No. 1 for priority benefit to its application No. 61/652,086, and its Opposition to the Senior Party's (the Broad Institute, Harvard University and MIT) Substantive Motion No. 1. The Broad for its part filed three additional substantive motions (Contingent Motion No. 2 to substitute the count; No. 3 to designate claims as not corresponding to the count; and No. 4, for priority benefit to the Broad's application No. 61/736,528). This post will discuss The Broad's Substantive Motion No. 2; future posts will review the remaining Broad motions and CVC's Substantive Motion No. 1.

This motion seeks to substitute the Count; Count 1 of the interference as declared is:

An engineered, programmable, non-naturally occurring Type II CRISPR-Cas system comprising a Cas9 protein and at least one guide RNA that targets and hybridizes to a target sequence of a DNA molecule in a eukaryotic cell, wherein the DNA molecule encodes and the eukaryotic cell expresses at least one gene product and the Cas9 protein cleaves the DNA molecules, whereby expression of the at least one gene product is altered; and, wherein the Cas9 protein and the guide RNA do not naturally occur together, wherein the guide RNAs comprise a guide sequence fused to a tracr sequence.

or

A eukaryotic cell comprising a target DNA molecule and an engineered and/or non-naturally occurring Type II Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR)-— CRISPR associated (Cas) (CRISPR-Cas) system comprising

a) a Cas9 protein, or a nucleic acid comprising a nucleotide sequence encoding said Cas9 protein; and

b) a single molecule DNA-targeting RNA, or a nucleic acid comprising a nucleotide sequence encoding said single molecule DNA-targeting RNA; wherein the single molecule DNA-targeting RNA comprises:

i) a targeter-RNA that is capable of hybridizing with a target sequence in the target DNA molecule, and

ii) an activator-RNA that is capable of hybridizing with the targeter-RNA to form a double-stranded RNA duplex of a protein- binding segment,

wherein the activator-RNA and the targeter-RNA are covalently linked to one another with intervening nucleotides; and

wherein the single molecule DNA-targeting RNA is capable of forming a complex with the Cas9 protein, thereby targeting the Cas9 protein to the target DNA molecule, whereby said system is capable of cleaving or editing the target DNA molecule or modulating transcription of at least one gene encoded by the target DNA molecule.

The Broad's proposed Count 2 is:

A method, in a eukaryotic cell, of cleaving or editing a target DNA molecule or modulating transcription of at least one gene encoded by the target DNA molecule, the method comprising:

contacting, in a eukaryotic cell, a target DNA molecule having a target sequence with an engineered and/or non-naturally-occurring Type II Clustered Regularly lnterspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR)-CRISPR associated Cas) (CRISPR-Cas) system comprising:

a) a Cas9 protein, and

b) RNA comprising

i) a targeter-RNA that is capable of hybridizing with the target sequence of the DNA molecule or a first RNA comprising (A) a first sequence capable of hybridizing with the target sequence of the DNA molecule and (B) a second sequence; and

ii) an activator-RNA that is capable of hybridizing to the targeter-RNA to form an RNA duplex in the eukaryotic cell or a second RNA comprising a tracr sequence that is capable of hybridizing to the second sequence to form an RNA duplex in the eukaryotic cell,

wherein, in the eukaryotic cell, the targeter-RNA or the first sequence directs the Cas9 protein to the target sequence and the DNA molecule is cleaved or edited or at least one product of the DNA molecule is altered.

The distinction the Broad makes is between embodiments of CRISPR methods that are limited to "single-molecule guide RNA" (aka "fused" or "covalently linked" species), versus embodiments that encompass single-molecule and "dual molecule" species (wherein the in the latter versions the "targeter-RNA" and "activator-RNA" as recited in the proposed Count are not covalently linked). The Broad argues that this Count should be adopted by the Board because it "properly describes the full scope of the interfering subject matter between the parties because both parties have involved claims that are generic, non-limited RNA claims." The brief also argues that proposed Count 2 "sets the correct scope of admissible proofs [i.e., their own] for the breakthrough invention described by the generic claims at issue in these proceedings—the successful adaption of CRISPR-Cas9 systems for use in eukaryotic environments," which The Broad contends current Court 1 (in either alternative) does not.

The brief also requests that the Broad be accorded benefit to its provisional application U.S. Serial No. 61/736,527, and that CVC not be accorded benefit to any of its earlier applications (which just maintains the status quo requiring CVC to move to be accorded benefit), because CVC's applications-in-interference were not accorded benefit when this interference was declared.

The Broad's argument in support of its motion is that Count 1 is too narrow for encompassing just a subset of the parties' involved claims. In particular, the brief asserts that most of the Broad's involved clams encompass "non-limited" RNA systems and methods. Similarly, the brief argues that CVC itself has many claims directed to non-limited RNA systems and methods and has entire applications that do not recite claims to non-limited RNA systems and methods. The Broad asserts that Count 1 does not permit the Broad to rely on its earliest and best proofs of invention, which the brief states is "plainly unfair." This unfairness would preclude the Broad from establishing what the brief terms "the fundamental breakthrough - the invention of use of CRISPR in eukaryotic cells" (emphasis in brief). Failing to substitute the Count would instead improperly focus the priority question on who invented the single molecule modification. Colorfully, the brief declares that "[a]llowing the interference to proceed with Count 1 would permit the (single molecule RNA) tail to wag the (breakthrough use of CRISPR in eukaryotic cells) dog."

The claims include such generic species that encompass both single-molecule and dual molecule embodiments, according to the brief, but the breakthrough invention was adapting CRISPR-Cas9 to be used in eukaryotic cells, an argument the Broad has used consistently here and in the earlier '048 interference to distinguish its claims from CVC's. The brief notes that the first disclosure of this use was in a scientific journal article by some of the Broad's named inventors that "has become by far the most frequently cited CRISPR publication" as evidence of the groundbreaking nature of the invention. Also cited (as a reminder to the Board of its earlier decision, the basis thereof and the Federal Circuit's affirmance of it) is the Board's earlier decision that there was no reasonable expectation of adapting CRISPR for use in eukaryotic cells as further evidence of the breakthrough nature of (as asserted herein) the Broad's invention.

It is then the Broad's turn to allege that its opponent is attempting to avoid this interference, "on fair terms," the question of which party invented use CRISPR in eukaryotic cells. The Broad sets out its allegations against CVC, first for "tr[ying] to engineer" the '48 interference on "environment-free" proofs, and now for "trying to engineer a single-molecule RNA eukaryotic CRISPR interference" that would prevent the Broad from relying on its best (i.e., early dual molecule RNA) proofs. Whereas, according to the Broad, CVC is attempting to rely on reduction to practice of single-molecule RNA systems that "occur[ed] over a year after Broad's alleged earliest reductions to practice" (emphasis in brief). The consequence of using Count 1 would raise "'the anomalous possibility' that CVC could win priority as to the full scope of the commonly claimed invention (and Broad could lose all of its designated claims, including non-limited RNA claims) merely by CVC proving priority based on a later reduction to practice on a limited count, even though Broad made the broad invention of the designated claims first."

Further, echoing arguments made in its Substantive Motion No. 1, using such an "artificially narrow count" would permit CVC to avoid the estoppel effects of the decision in the '048 interference, according to the Broad. The brief cites a CVC press release touting the risk this interference provokes that "jeopardizes all of the Broad's CRISPR patents as (somehow) being evidence that CVC is unfairly trying to obtain an undeserved windfall in its interference strategy (ignoring the fact that it was the PTO that declared the interference and determined the Count).

The Broad then provides the Board with, in the alternative, either proceeding with this interference under Count 1 but finding that non-limited RNA claims do not correspond to the Count, or proceeding with a two Count interference, with one Count directed to using CRISPR in eukaryotic cells and the other directed to single-molecule RNA species.

The brief then sets forth the differences between non-limited and single-molecule RNA versions of CRISPR, and its history of the development of its eukaryotic cell embodiments of CRISPR technology, making distinction between single-molecule RNA and dual molecule RNA embodiments, and liberally illustrating the brief with diagrams from its own NIH grant applications and scientific references. The brief then synopsizes the decision in the earlier '048 interference based on there being no reasonable expectation of success in achieving eukaryotic cell applications of CRISPR based on earlier applications of CRISPR in prokaryotic cells. This was followed by the Broad's description of the CVC's further prosecution of the applications in this interference.

Section V of the brief adopts the format of motions in interference practice of setting forth the basis for the PTAB to grant the motion. For motions such as this one, the standard is that the current Count does not encompass the full scope of the interfering subject matter and excludes the Broad's best proofs. See, Grose v. Plank, 15 U.S.P.Q.2d 1338, *4-6 (B.P.A.I. 1990); Kondo v. Martel, 220 U.S.P.Q. 49, *2-3 (B.P.A.I. 1983); Nelson v. Drabek, 212 U.S.P.Q. 98 *2-3 (Comm'r 1979). The interfering subject matter, according to the Broad, is claims to non-limited RNA (i.e., single molecule and double molecule species of RNA) for use in eukaryotic cells; the grounds for this allegation is that each party has involved claims to this subject matter. The crux of this argument (echoed throughout) is that "the Count should be set to resolve the parties' dispute as to who made the breakthrough necessary to make CRISPR Cas9 systems and methods work in a eukaryotic environment first, not just which party first disclosed 'fused' or 'covalently-linked' guide RNA," citing In re Van Geuns, 988 F.2d 1181, 1184 (Fed. Cir. 1993). Doing otherwise (i.e., maintaining Count 1) would result (according to the Broad) in the Board awarding priority "not to the party that invented [use of CRISPR in eukaryotic cells] first, but rather to whomever can show they made the single molecule modification to that invention first."

The Broad contends that Count 1 puts all their claims at risk (a complaint contrary to arguments that the Board should settle the interference (in their favor) once an for all. And the brief reiterates the allegation that this is fundamentally unfair because CVC made a "its deliberate decision to not include eukaryotic CRISPR claims in the 048 Interference, in which Broad could have used proofs commensurate in scope with the scope of its claims."

Next the Broad sets forth its arguments why the PTAB should grant the motion and substitute this Count 2. First, according to the brief, Count 2 is consistent with the scope of the parties' claims and properly describe the scope of the interfering subject matter. Because the Broad has proofs relating to using dual molecule RNA in CRISPR prior to CVC's claims-in-interference, and limiting their proofs to single molecule embodiments (which cannot antedate CVC's claims in interference) would limit the extent to which the Broad could counter CVC's priority proofs. And as they have argued elsewhere, CVC's own public statements are used to imply that Berkeley and its colleagues are pursuing the broader scope because it puts essentially all the Broad's patents at risk (ignoring for the purpose of its argument that CVC did not provoke this interference or suggestion this Count No. 1, both of which are sua sponte creatures of the PTAB itself).

With regard to its "best proofs" argument, the Broad cites caselaw (Univ. of S. California v. DePuy Spine, Inc., 473 F. App'x 893, 23 895 (Fed. Cir. 2012)) the Board's regulations (37 C.F.R. § 41.121, § 41.201, and § 41.208(a)(2)); and the MPEP (MPEP § 2304.02(b)) in support of its position. The brief supplements these citations with what CVC is "likely" to argue, i.e., "that Broad is barred from relying on some of its best proofs supporting priority as to its non-limited claims, which are the vast majority of its involved claims." Those "best proofs" are duel-molecule guide RNA embodiments used in eukaryotic cells that the Broad contends are entitled to a filing date in 2012 earlier than any possible CVC priority date, based inter alia on affidavit testimony submitted with its brief in addition to declarations and laboratory evidence submitted during ex parte prosecution. And of course the Broad reminds the Board that the consequence could be awarding priority to a later inventor, contrary to the purpose of interferences.

In the alternative, the Broad argues that should the PTAB determine that the estoppel the Broad argued in Substantive Morton No. 1 does not apply, and that the interference will proceed under Count 1, the PTAB should designate the Broad's claims directed to dual-molecule RNA embodiments as not corresponding to Count 1, or sua sponte declare a two Count interference.

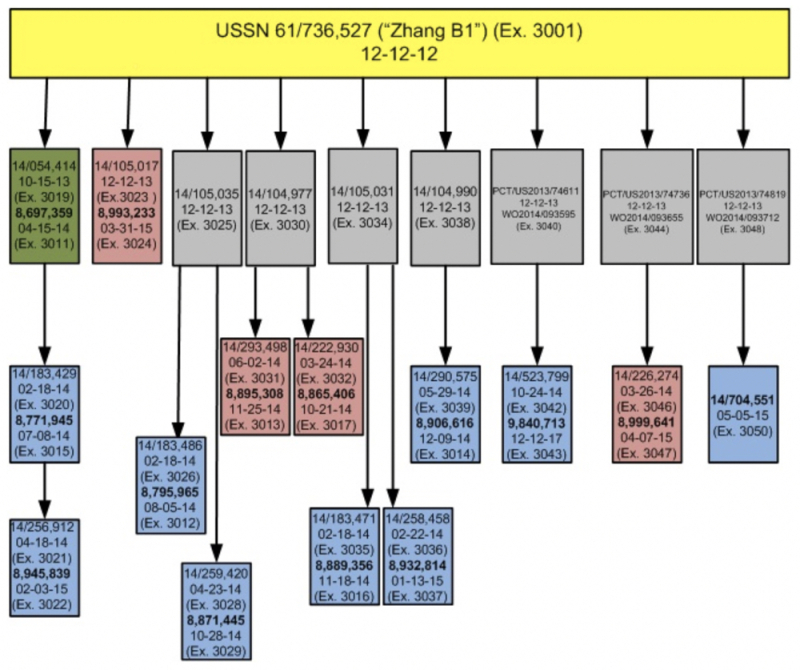

The brief next turns to the benefit of priority to which they are entitled under Count 2, specifically the Zhang B1 reference and any intervening patents or applications claiming priority to USSN 61/736,527 (Zhang B1), illustrated by this diagram and supported by evidence set forth in Appendix 3:

The brief then sets forth, in detail, element-by-element, support in Zhang B1 for the recited elements of the Count. Also recited is the asserted basis for priority in each of the related, later-filed applications set forth in the diagram, as well as the '945, '965, '445, '356, '814, '839, '616 and '713 Patents and '551 application, thus reaffirming that these patents-in-interference were entitled to the priority claim.

In contrast, the Broad argues that CVC is not entitled to any priority, based in part because there was no benefit of priority was accorded by the Board when this interference was declared.

Section V.F. then argues that Count No. 2 recites subject matter that is patentable over the prior art, when considered in light of the Broad being entitled to the December 12, 2012 filing date of the Zhang B1 reference, first by analogy to the subject matter of the Count in the '048 Interference (and, extensively, the PTAB's decision in that interference and the Federal Circuit' affirmance thereof) and also because the Broad's claims corresponding to Count No. 2 had been allowed over the prior art of record.

Finally, the Broad's brief argues which of its claims correspond to Count No. 2:

USP 8,697,359 – Claims 1-20 (all); USP 8,771,945 – Claims 1-29 (all); USP 8,795,965 – Claims 1-30 (all); USP 8,889,356 – Claims 1-30 (all); USP 8,906,616 – Claims 1-30 (all); USP 8,945,839 – Claims 1-28 (all); USP 8,993,233 – Claims 1-6 and 8-43; USP 8,999,641 – Claims 1-28 (all); USP 9,840,713 – Claims 1-41 (all); and UPS 14/704,551 – Claims 2, 4-8, and 12-18

And which do not (and arguments in support of its designations). The brief also sets out which of CVC's claims so correspond (all of them).