Last Friday, May 3, 2019, the Federal Circuit affirmed a decision by the District Court that Defendants Actavis LLC and Teva Pharmaceuticals did not show by clear and convincing evidence that the claims asserted by Endo Pharmaceuticals Inc. and Mallinckrodt LLC were obvious, in Endo Pharmaceuticals Inc. v. Actavis LLC, over a strong dissent by Circuit Judge Stoll.

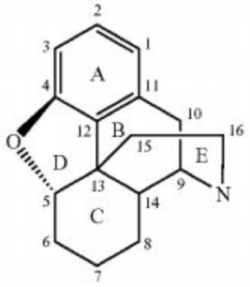

The case arose in ANDA litigation over Mallinckrodt's U.S. Patent No. 8,871,779 licensed to Endo; the asserted claims were directed to methods for making morphinan-6-one products having low levels of α,β unsaturated ketones; relevant pharmaceuticals have the generic structure:

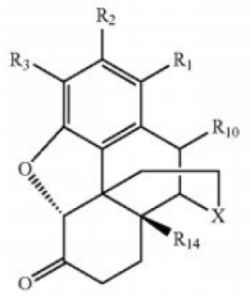

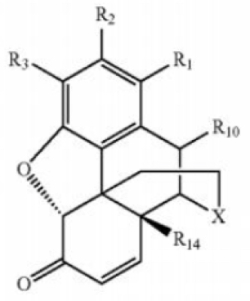

wherein the ketone is present at position 6 of the C ring and the α and β positions are numbered 7 and 8 in the formula, respectively. Prior art methods of making such compounds resulted in deleterious impurities wherein the α and β positions were unsaturated, i.e., retaining "double bonds between the α and β carbon atoms" despite undergoing catalytic hydrogenation to reduce them. Treatment of these compounds with heat in the presence of a sulfur-containing compound, according to the specification of the '779 patent, reduced these impurities to "acceptable levels" (less than 0.5%). The asserted claims were set forth in the opinion as follows:

1. A hydrochloride salt of oxymorphone comprising less than 0.001% of 14-hydroxymorphinone.

2. The hydrochloride salt of claim 1 comprising less than 0.0005% of 14-hydroxymorphinone.

3. A pharmaceutical acceptable form comprising the oxymorphone hydrochloride according to claim 1.

4. A hydrochloride salt of a morphinan-6-one com-pound corresponding to Formula (2):

comprising less than 0.001% measured by [high performance liquid chromatography] of [a compound] corresponding to Formula (3):

comprising less than 0.001% measured by [high performance liquid chromatography] of [a compound] corresponding to Formula (3):

wherein the morphinan-6-one compound is oxymorphone and wherein X is —N(R17)—;

R1 and R2 are hydrogen;

R3 is hydroxy;

R10 is hydrogen;

R14 is hydroxy; and

R17 is methyl.

5. The hydrochloride salt of claim 4 comprising less than 0.0005% of 14-hydroxymorphinone.

6. A pharmaceutical formulation comprising the oxymorphone hydrochloride according to claim 4.

Defendants asserted three prior art references in support of their invalidity arguments. The Weiss reference, a 1957 scientific publication, disclosed the use of catalytic hydrogenation to produce oxymorphone, a compound falling within the scope of the asserted claims that specifically addresses reducing α,β unsaturated ketones. The Chapman reference, U.S. Patent Application Publication No. 2005/0222188, disclosed catalytic hydrogenation to reduce α,β unsaturated ketones of oxycodone into a salt form of the drug. Finally, the Rapoport reference, a 1967 scientific publication, disclosed a process employing bisulfite addition to convert α,β unsaturated oxycodone to saturated oxycodone that uses solubility differences to separate the unsaturated from the saturated forms of the drug. None of these references were sufficient to convince the District Court, which found that Actavis and the other Defendants did not prove by clear and convincing evidence that the claims were invalid under either §§ 102 or 103. This appeal followed.

The Federal Circuit affirmed, in an opinion by Judge Wallach joined by Judge Clevenger over Judge Stoll's dissent. The majority first addressed the District Court's claim construction regarding the claim term "14-hydroxymorphinone" which Defendants argued was error, and then their argument that the District Court erred in its nonobviousness determination. The District Court in this case relied on both intrinsic evidence (here, the claim language and specification) and extrinsic evidence (expert testimony from both plaintiff and defendants experts) in construing the term "14-hydroxymorphinone" to mean "14-hydroxymorphinone hydrochloride," i.e., the salt form of the drug. Actavis and the other Defendants argued that the District Court should have interpreted the term using its plain meaning; the Federal Circuit majority disagreed. According to the opinion, claims 1 and 2 expressly recite the hydrochloride salt of the drug, and claim 3 (dependent on claim 1) sets forth the structure instead of using the term "14-hydroxy-morphinone"; the remaining claims are consistent with the interpretation that the asserted claims only recite "14-hydroxy-morphinone" "as part of the salt-, or hydrochloride-, form of the claimed compounds" (emphasis in opinion). Accordingly, the plain meaning of the claim language is consistent with the District Court's interpretation of the term "14-hydroxymorphinone" to mean "14-hydroxymorphinone hydrochloride."

With regard to the specification, the panel majority found an express example (Example 3) that refers to the reaction(s) producing the claimed compounds as involving the hydrochloride salt of the drug. Taken as a whole, however, the panel held that the use of the term in the "broader specification [was] relatively unsupportive of either proffered construction." (In a footnote, the opinion explained that "neither the parties nor we have identified anything in the prosecution history that further elucidates the proper construction of this limitation.")

Regarding the extrinsic evidence, the opinion cites admissions by Defendants' expert conceding that a person of ordinary skill would have understood that Example 3 described a reaction using the salt form of the drug. As a consequence of these analyses, the Federal Circuit held that the District Court had not erred in construing the claim term "14-hydroxymorphinone" to mean "14-hydroxy-morphinone hydrochloride."

Turning to the District Court's determination that Defendants had not carried their burden of establishing obviousness by clear and convincing evidence (the opinion explaining that the anticipation argument required the panel to agree with Defendants' construction and thus its decision to the contrary obviated the need to address this argument on appeal), the panel majority held that the District Court did not clearly err in finding that the skilled worker would not have had a reasonable expectation of success in achieving the claimed invention by combining the asserted prior art. Specifically, the District Court held that the combination of the teachings of the Chapman reference to the reaction described in the Weiss reference would not satisfy the reasonable expectation requirement for establishing obviousness. Additionally, the Rapoport reference did not teach that bisulfite could be used to reduce the unsaturated impurities known to exist in prior art synthetic method. The panel majority held that the absence of "key reaction conditions" (according to Endo's expert) in the cited art as well as the absence of "purification to the degree claimed" in the '779 patent (according to testimony by both Endo's and Actavis's experts) supported the District Court's conclusion that Defendants failed to establish obviousness. The opinion also credits the District Court's assessment of the Rapoport reference as not providing a reasonable expectation of success in using bisulfite treatment to remove oxycodone impurities that could achieve the purity levels claimed in the '779 patent, based on expert testimony.

In an interesting footnote, the panel majority also described confidential communications from the Food and Drug Administration to opioid drug manufacturers that 1) were not public, and 2) did not disclose any methods for achieving reduced unsaturated contaminants that the panel majority (contrary to the District Court) determined were relevant to the obviousness inquiry. Ultimately, the majority held that these communications were insufficient to satisfy the reasonable expectation of success needed for an obviousness determination, because inter alia, "the FDA communications recite a goal without teaching how the goal is attained" and "these communications would not have been enough to overcome the disclosures of Weiss, Chapman, and Rapoport, which indicate that a PHOSITA would not reasonably believe their disclosed methods were fruitful avenues to achieve the FDA-mandated oxymorphone purity level." This conclusion was supported by testimony from the '779 patent inventors regarding the "extensive experimentation, involving much failure, [required] to ultimately produce [] oxymorphone" having the claimed purity levels with regard to α,β unsaturated ketone impurities.

Judge Stoll dissented, based on the FDA's regulatory requirements which, in her view, set forth "every limitation of claim 1" of the '779 patent. The District Court further erred in her opinion by "imposing a requirement that a reference must teach how to solve a problem to provide a motivation to combine, conflating enablement and reasonable expectation of success requirements with motivation" (emphasis in opinion). And finally, Judge Stoll found error in the District Court "appl[ying] an erroneously heightened standard for reasonable expectation of success by requiring a 'definitive solution' and proof of actual success." The Judge in her dissent acknowledged the deference due a district court's factual findings, but "such deference is not due where the trial court applies the incorrect standard to arrive at those findings." After setting forth her reasoning concerning the District Court's errors in applying the standards for making a proper obviousness determination, Judge Stoll concluded by stating:

This is not a typical Hatch-Waxman case where the patentee provided the public with a new drug, formulation, or manufacturing process. While Mallinckrodt's patent specification is directed to a specific process for achieving the FDA's objective, Mallinckrodt did not claim that process. Mallinckrodt instead claimed the FDA mandate. The FDA sought to make oxymorphone safer for the public and Mallinckrodt took advantage by claiming the directive itself, securing exclusive rights to a drug first approved in 1959. This is not the type of innovation that the patent system and the obviousness standard were designed to protect.

Endo Pharmaceuticals Inc. v. Actavis LLC (Fed. Cir 2019)

Panel: Circuit Judges Wallach, Clevenger, and Stoll

Opinion by Circuit Judge Wallach; dissenting opinion by Circuit Judge Stoll