Video Doorbell Patent Found to Be Patent Eligible

Plaintiff Eyetalk365, LLC sued Defendant Zmodo Technology Corp. for infringement of U.S. Patent No. 9,432,638, entitled "Communication and Monitoring System," which issued on August 30, 2016. Zmodo moved to dismiss for failure to state a claim under 35 U.S.C. § 101.

The patent is directed to an audio-video doorbell system. The patent describes that the invention enables secure and effective monitoring and interacting with a visitor at a residence or business, including, detection of the presence of a visitor at the exterior of the home or office via a proximity sensor, the interactive communication with the visitor, whether an occupant is present or absent from the home or office, the enablement of automated entry into the home or office by the visitor, and personalization of the process of receiving a visitor. Such actions are permitted through use of a cell phone app that receives information from the doorbell system, and enables the user to communicate with a person at their home even when absent from their home.

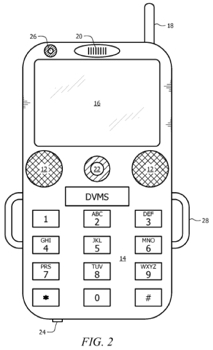

A transceiver, shown in Figure 2 of the patent reproduced below, may be mounted at the front door of a home and used to provide these features.

Claims 1 and 6 of the patent are asserted, of which claim 1 is representative and reproduced below.

1. A method for receiving a person at an entrance, comprising the steps of:

(a) detecting the presence of a person at the entrance;

(b) transmitting, to a computerized controller running a software application, video of the person at the entrance recorded using a camera located proximate the entrance; and

(c) providing, with the software application running at the computerized controller, a graphical user interface to a remote peripheral device by which a user of the remote peripheral device, which comprises a cell phone, may view the video of the person at the entrance;

wherein said detecting of step (a) comprises using a wireless video camera comprising a microphone, a speaker, an RF receiver, an RF transmitter, a proximity sensor and uses a keypad comprising one or more buttons to determine that the person is present at the entrance wherein said transmitting of step (b) comprises transmitting digital streaming video wirelessly using the video camera;

(d) sending an alert to the cell phone that the person is present at the entrance after the keypad is pressed by the person at the entrance;

(e) speaking with the person at the entrance through the graphical user interface on the cell phone after the keypad is pressed by the person at the entrance; and

(f) listening to the person at the entrance via the cell phone through use of the graphical user interface after the keypad is pressed by the person at the entrance.

Patentability under 35 U.S.C. § 101

The Court was quick to note that there is a lack of clarity in the test for abstractness challenges under § 101. Applying the two-step test under Alice Corp., the Court noted that the best test for abstractness under the first Alice Corp. step is whether the invention can be practiced entirely in the mind of a sufficiently intelligent person.

Namely, citing CyberSource, the Court noted that such a method that can be performed by human thought alone is merely an abstract idea and is not patent-eligible under § 101. Methods which can be performed entirely in the human mind are unpatentable not because there is anything wrong with claiming mental method steps as part of a process containing non-mental steps, but rather because computational methods which can be performed entirely in the human mind are the types of methods that embody the "basic tools of scientific and technological work" that are free to all men and reserved exclusively to none.

Zmodo argued that claim 1 is directed to an abstract idea under the first Alice Corp. step, but the Court disagreed. Detecting the presence of a person at a door, sending a video of the person to be viewed, and speaking with the person at the door are all concrete steps requiring more than the abstract thinking capabilities of a person or a computer.

Zmodo further argued that claim 1 did not recite anything new or useful, and attempted to prove that elements of claim 1 were all directed to old technology. However, the Court noted that regardless of anticipation or nonobviousness under §§ 102 and 103 -- neither of which is at issue in the present motion or for consideration under § 101 -- the Court found claim 1 to be patent-eligible under § 101.

The Court clearly set out that the "novelty" of any element or steps in a process, or even of the process itself, is of no relevance in determining whether the subject matter of a claim falls within the § 101 categories of possibly patentable subject matter.

A contrary approach would judicially rewrite the statutory framework for patent validity established by Congress by invalidating a patent not under §§ 101 or 102 but rather under a hybrid of §§ 101 and 102 that Congress has never adopted. The Supreme Court has declined to do so and has made clear that patent claims must be tested against the statutory requirements for validity as a whole. That is because it is patent claims, i.e., inventions, to which a patentee is granted exclusive rights, not the elements of a claim.

Thus, the Court denied the motion to dismiss.

This is a short Order, but positive from a patent owner's viewpoint in that not all Courts use § 101 erroneously to invalidate claims. It would seem that clearly steps of "transmitting, to a computerized controller running a software application, video . . .", and "detecting . . . using a wireless video camera comprising a microphone, a speaker, an RF receiver, an RF transmitter, a proximity sensor and uses a keypad comprising one or more buttons to determine that the person is present at the entrance . . ." include features that qualify as patentable subject matter.

Other features in claim 1 of "(e) speaking with the person . . ." and "(f) listening to the person . . ." would be examples, however, of features covering patent ineligible subject matter since these actions are capable of being performed by a human alone. This was the distinction that the Court relied upon in its decision.

Order by District Judge Robert C. Jones