August 27, 1890

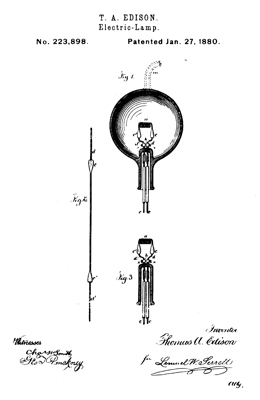

WASHINGTON D.C. The ups and downs of Mr. Thomas A. Edison's inventions related to electrical lighting continue. After his U.S. Patent No. 223,898 for an "Electric Lamp" was found to be valid in the Circuit Court of the Western District of Pennsylvania, the case was appealed to the Federal Circuit. Oral arguments were held this Spring and the decision of the Court came down last week, invalidating Mr. Edison's claims.

The Court (a panel of three appellate judges) applied curious reasoning. They began by describing what they referred to as "laws of nature" and "natural phenomena" -- properties of nature that exist independently of the human experience -- one of which was the basis of the invention:

Incandescence is a form of thermal radiation that results from heating a body to the point that it produces visible light. Virtually all solids and liquids exhibit incandescence if a proper amount of heat is applied, as described in Lardner's 1833 Treatise on Heat. Indeed, light from the sun is generated from incandescence. Thus, incandescence is a natural law; that is, a phenomenon that is produced by nature and not the hand of humankind.

The Court went on to explain that, to be patentable, an invention based on a natural phenomenon must include an inventive concept that is not "well-understood, routine, and conventional" and that provides "significantly more" than the excluded phenomenon itself. Otherwise, one could patent "what should be in the public domain and free for all to use as they see fit." Ultimately, the Court found that Mr. Edison's patent did not meet this requirement and was therefore an improper attempt to obtain a patent on an effect of the world we live in rather than an inventive modification thereof.

The claims of the '898 patent recite:

1. An electric lamp for giving light by incandescence, consisting of a filament carbon of high resistance, made as described, and secured to metallic wires, as set forth.

2. The combination of carbon filaments with a receiver made entirely of glass and conductors passing through the glass, and horn which receiver the air is exhausted, for the purposes set forth.

3. A carbon filament or strip coiled and connected to electric conductors so that only a portion of the surface of such carbon conductors shall be exposed for radiating light, as set forth.

4. The method herein described of securing the platina contact-wires to the carbon filament and carbonixin of the whole in a closed chamber, substantially as set forth.

Based on their broad language, the Court rapidly concluded that "the claims clearly involve a laws of nature, namely that of generating incandescence by heating a resistive wire through conduction of electricity." Justifying this decision, the Court wrote, "[p]henomena of nature, though just discovered, are not patentable, as they are basic and fundamental to ongoing scientific and technological work, and monopolization of such central principles through the grant of a patent might tend to impede innovation rather than promote it."

The Court made analogies to other discoveries of natural laws, and noted that "Newton could not have patented his celebrated discovery of law of gravity nor could Pythagoras have patented his theorem regarding relationship between the side lengths of a right triangle . . . [l]ikewise, we cannot affirm the validity of a patent on a fundamental process of the physical universe that likely existed well before the Earth itself."

Having establishing that Mr. Edison's claims are directed to a natural phenomenon, the Court addressed the follow-on question of whether those claims were drawn narrowly and to an unconventional application thereof. The Court observed that, "[t]o transform an unpatentable law of nature into a patent-eligible application of such a law, one must do more than simply state the law of nature while adding the words 'apply it.'" Such a claim, in the Court's view, would just be "a clever drafting exercise designed to monopolize the law of nature itself."

Thus, the Court considered the language of the claims, looking for the aforementioned inventive concept in the additional elements. In doing so, it determined that these elements encompassed "metallic wires, glass, and a closed chamber," but that each was in routine use by experimenters at the time of Edison's invention.

The Court observed that the claimed metallic wires are conventional means for conducting electricity, and that it is routine to perform laboratory tests inside a chamber to prevent reactions from being contaminated by the outside world. Moreover, performing such a well-understood process in a controlled environment is a fundamental basis of experimentation. The extension of the laboratory testing conditions to an end product by sealing a glass chamber containing the "filament of high resistance" is nothing more than a conventional application of such laboratory conditions. As examples of the well-understood nature of the additional elements, the Court pointed to the 1761 work of Ebenezer Kinnersley in heating metallic wires to incandescence, the Belgian Marcellin Jobard who produced an incandescent light bulb in 1838 using a vacuum chamber, as well as the Russian Alexander Lodygin who, in 1872, demonstrated an incandescent light bulb in a glass enclosure.

Moreover, Mr. Edison stated in his patent that others have already been able to produce light through incandescence:

Heretofore light by incandescence has been obtained from rods of carbon of one to four ohms resistance, placed in closed vessels, in which the atmospheric air has been replaced by gasses that do not combine chemically with the carbon.

Mr. Edison went on to state that "[t]he leading-wires have always been large, so that their resistance shall be many times less than the burner." Because incandesce through one to four ohm resistance filaments was known, the Court observed that the basic application of the scientific principles of Ohm's and Joule's laws dictates that a higher-resistance filament would simply cause a reduction of the current required to cause incandescence. Therefore, based on these scientific principles, smaller wires and less power would be needed for incandesce. Thus, in the Court's view, Mr. Edison has conceded both that incandescence from carbonized elements in closed vessels and that the claimed structure and ratios of resistances between wires and filaments were already known.

Particularly, Mr. Edison does not claim that he created a new apparatus. Indeed, "Mr. Edison did not invent the claimed electric light structure, nor was he the first to observe the physical phenomena of incandescence." Instead, "Mr. Edison simply uses well-known components for their intended use according to the principles dictated by established laws of electronics."

Thus, the Court found that "[t]hese conventional components, all generic, are unable to transform the claimed invention into significantly more than the natural phenomenon." Furthermore, "when considered in combination, these elements add nothing beyond the elements individually, and the combination of elements fails to improve the functioning of an electronic bulb beyond what is expected by laws of nature."

Mr. Edison argued that because "the particular laws of nature that the claims embody are narrow and specific, the patents should be upheld." But the Court disagreed, stating that "[a] patent upon a narrow law of nature may not inhibit future research as seriously as would a patent upon Newton's discoveries, but the creative value of Mr. Edison's discovery is also considerably smaller." Moreover, "even a narrow law of nature can serve to inhibit future research."

The Court concluded, "[f]or these reasons, we hold that the patent claims at issue here effectively encompass the underlying laws of nature themselves and are consequently invalid."