The purpose of this quarterly tracker is to identify key federal and state health AI policy activity. Below reflects federal legislative and regulatory activity to date related to AI, and state legislative activity introduced between January 1 and March 31st, 2024. This summary is current as of March 31, 2024 and will be refreshed at the end of Q2 (June 2024).

Artificial intelligence has been used in health care since the 1950s, but recent technological advances in generative AI have expanded the potential for health AI to enable improvements in clinical quality and access, patient and provider experience, and overall value.

The AI legal and regulatory landscape is rapidly evolving as federal and state policy makers work to determine how AI should be regulated to balance its transformative potential with concerns regarding safety, security, privacy, accuracy, bias. Initial efforts have focused on improving transparency between the developers, deployers and users of AI technology. While there is currently no federal law specifically governing AI, the White House and several federal agencies have begun or are expected to propose laws and regulations to govern AI. The Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC), Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), Office of Civil Rights (OCR), Food and Drug Administration (FDA), Department of Justice (DOJ), Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and others have begun or are expected to propose laws and regulations to govern AI. We expect a flurry of activity in the second half of 2024 and beyond as deadlines included in President Biden’s Executive Order on responsible AI approach and pass.1 For a summary of key federal activities to-date, please see table here:

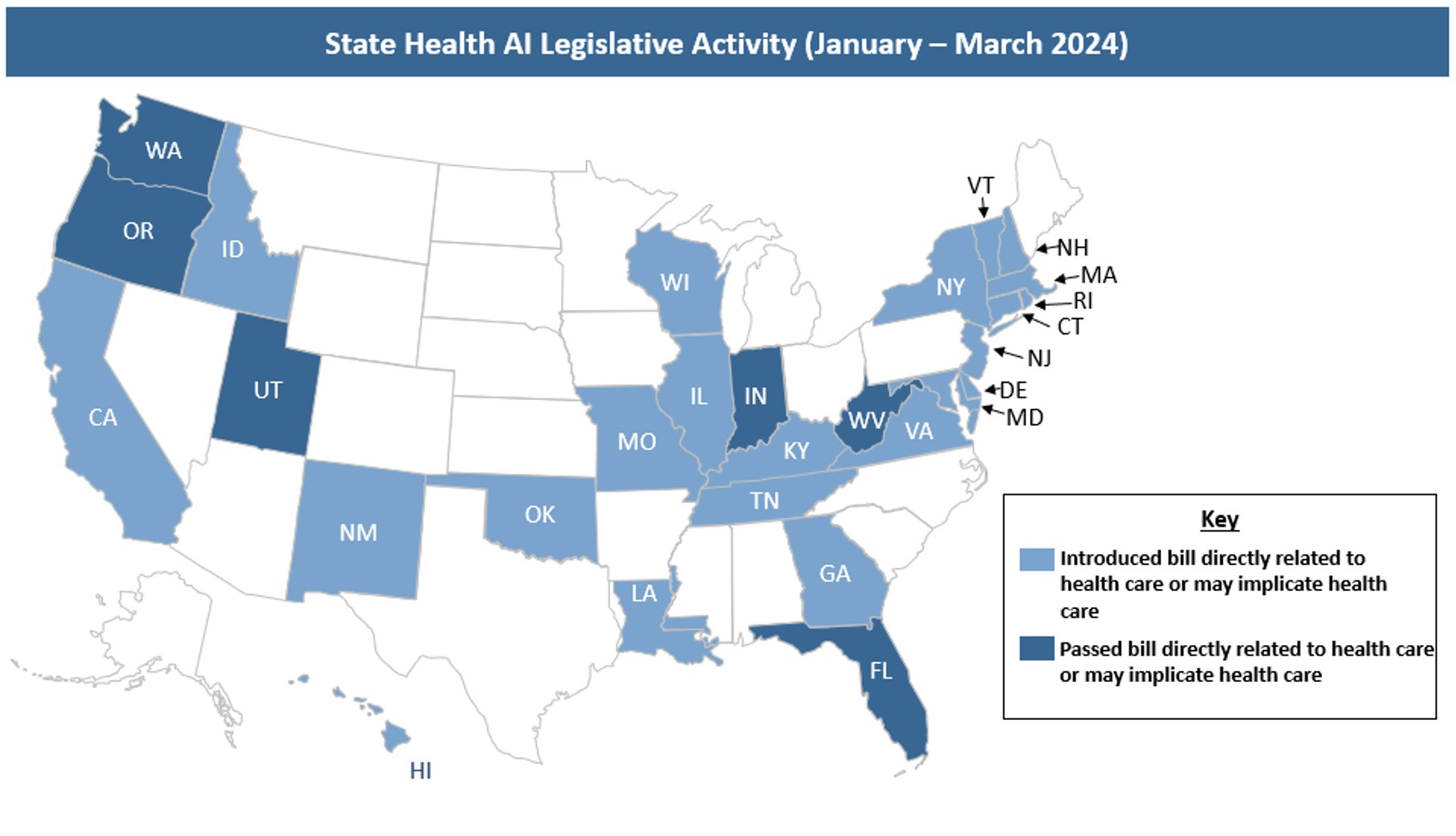

Notably, states are not waiting for federal guidance – and many have begun to introduce legislation that would implicate the use of AI across the health care landscape.

State Health AI Legislative Activity (January-March 2024)

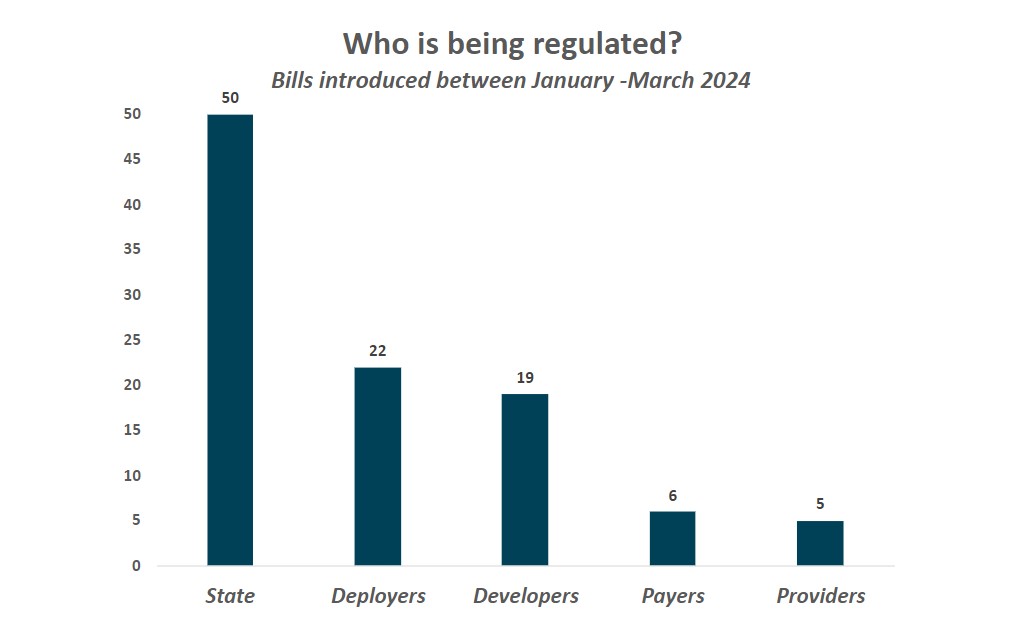

In the first quarter of 2024, states introduced legislation focused on a wide range of issues that implicate health care stakeholders. As shown below, proposed legislation regulates states, payers, providers, deployers, and developers. “Deployer” describes entities that use an AI tool or service and – depending on the precise use or definition within a bill – could include states, providers, payers, or individuals. “Developer” describes entities that make or build AI tools, which – again, depending on the precise use or definition within a bill – may include anyone developing AI, such as technology companies, states, providers or payers. Additionally, a bill that regulates state agencies could potentially impact other stakeholders, for example if an entity is a contractor or agent of the state or the requirements have downstream effects on developers or deployers.

Bills were identified as relevant if they regulated activity that fell into one of the following categories:

5

5

6

6

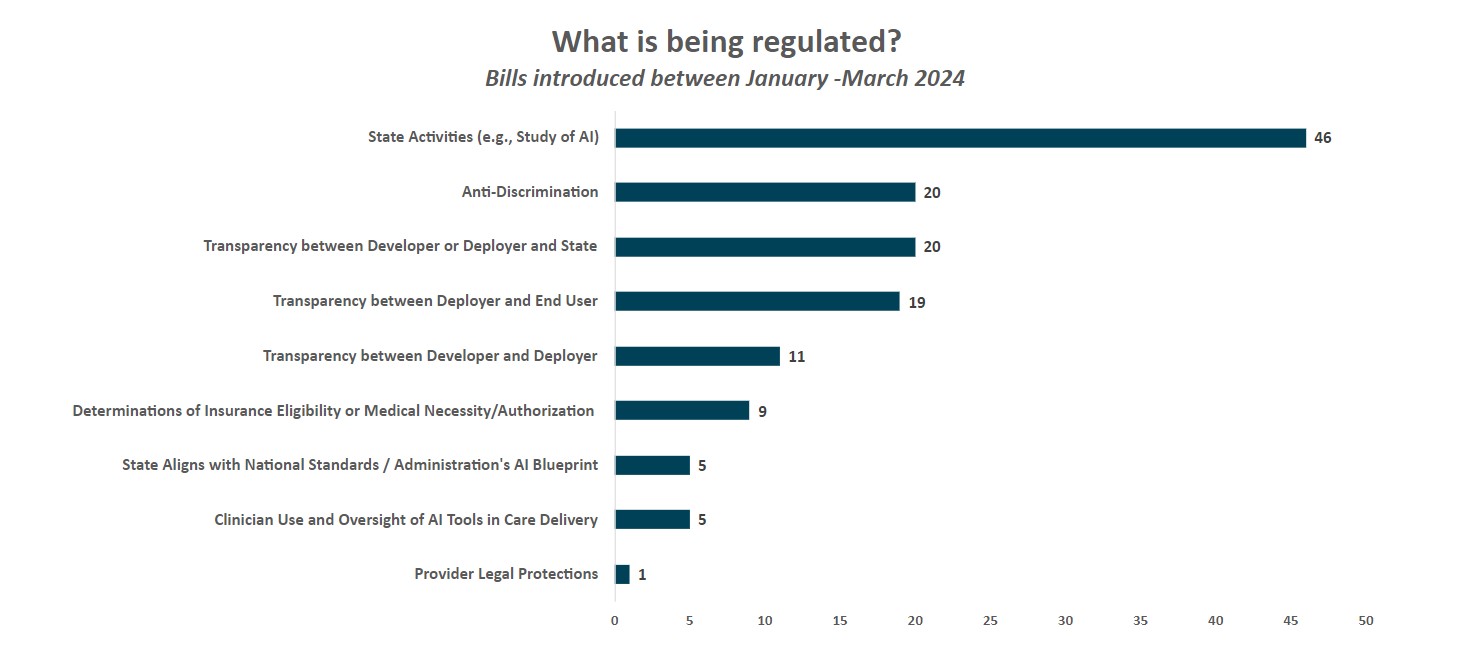

As shown above, key trends from health AI bills introduced between January – March 2024 include:

1. The majority of legislative activity relates to states mandating study bills, working groups or reports on AI to inform future policy making (46 bills). More than half of the bills tracked this quarter fell into this category:

- More than 20 bills would create AI task forces/committees (e.g., CT SB2 would establish an “AI Advisory Council” to make recommendations on the development of ethical and equitable use of AI in state government) and/or require completion of a one-time or annual study or report on AI (e.g., IL HB4705 would require state agencies to submit annual reports on algorithms in use by each agency)

- More than 10 bills either would require states to conduct inventories of AI systems used in state government (e.g., ID HB568 would require executive and legislative branch agencies to submit an inventory of all automated decision systems used by October 1, 2024), require states to complete impact assessments of AI systems used by state actors (e.g., OK HB3828 would prohibit state agencies from deploying AI systems without first performing an impact assessment), or affect public procurement of AI systems (e.g., NM HB184 would require government AI procurement contracts to include a requirement for transparency by the vendor)

- Seven bills would create new AI leadership positions to guide policy or align AI procedures across state government (e.g., NJ HB1438 would require the appointment of an AI Officer to develop procedures regulating the use of automated systems by state agencies making “critical decisions”7 [including those implicating health care] and organize an inventory of automated systems used by the state and the appointment of an AI Implementation Officer who would approve or deny state agency use of automated systems based on established state procedures).

The majority of these bills were focused on the general use of AI, rather than AI in health care specifically, although the implications of findings from these studies/reports may implicate the future use or regulation of AI in health care. Several bills require participation from health care stakeholders (e.g., MD HB1174 would require the Secretary of Health (or designee) and a representative from the Office of Minority Health and Health Disparities to serve on the “Technology Advisory Commission”; HI HB2176 would require “a representative of the health care industry” to serve on the AI working group; see also RI HB7158, WV HB5690, FL SB1680, among others). There were also a handful of bills more specific to health care and AI in health (e.g., FL SB7018 creates the “Health Care Innovation Council” to regularly convene subject matter experts to work towards improved quality and delivery of health care, including convening AI experts as necessary).

2. States are introducing bills focused on transparency between those who develop AI tools and those who deploy them, between those who deploy them and end users, and/or between those who develop or deploy them and the state.

-

Transparency between developers and deployers (11 bills). Bills were included in this category if they specified communication requirements between those who build AI tools (“developers”) and those who deploy them (“deployers”). The majority of bills in this category also included transparency requirements between deployers and end users as well as transparency requirements between developers/deployers and the state.

Specific transparency requirements vary but generally focused on ensuring that developers are providing background information on the tools’ training data, best use cases, and potential tool limitations to the entities purchasing or deploying the tools. For example, Virginia and Vermont introduced similar bills (VA HB747, VT HB710) that each would require developers to provide deployers – prior to the selling, leasing, etc. of AI tools – documentation that describes the AI’s intended uses, training data types, data collection practices, and steps the developer took to mitigate risks of discrimination, among other requirements. Other states proposed similar bills (e.g., IL HB5322, OK HB3835, and RI HB7521).

These bills would apply to health care stakeholders who are developers or deployers.

-

Transparency between deployers and end users (19 bills). Bills were included in this category if they specified disclosure or transparency requirements between deployers and those who are impacted by AI tools (i.e., end users). Illinois HB5116 would require deployers that use AI tools to make “consequential decisions”8 (which include decisions relevant to health care or health insurance) to notify individuals at or before the use of the AI tool that AI is being used to make, or is a factor in making, the consequential decision (similar to VA HB747). Illinois has another proposed bill, IL HB5649, that would make it unlawful for a licensed mental health professional to provide mental health services to a patient through the use of AI without first disclosing that an AI tool is being used and obtaining the patient’s informed consent.

Several bills were not specific to the provision of health care or health insurance, but apply to health care. For example, Florida introduced a bill (FL HB1459) that states: “an entity or person who offers for viewing or interaction a chatbot, image, audio or video output generated by artificial intelligence for commercial purpose to the Florida public in a manner where the public would reasonably believe that such output is not generated using artificial intelligence must adopt safety and transparency standards that disclose to consumers that such chatbot, image, audio, or video output is generated by artificial intelligence”. Wisconsin introduced language (WI HB1158) specific to generative AI, stating that any generative AI application must provide “in the same location as the conversation or instant message, a prominent and legible disclaimer that the generative artificial intelligence is not a human being”. If passed, these bills would require providers, health administrators, payers, and others that use chatbots to communicate with patients – e.g., to schedule an appointment or answer questions on coverage or eligibility – to include a disclaimer that the information provided originated from an AI tool.

-

Transparency between developer or deployer and state (20 bills).These bills require developers/deployers of AI tools to submit specific information or impact assessments to the state and/or to register AI tools with the state.

Two unique bills originated in Oklahoma and New York. Oklahoma HB3577 would require payers to submit AI algorithms and training data used for utilization review to the state. New York SB8206 would require “every operator of a generative” AI system to (1) obtain an affirmation from users prior to the tool’s use that the user agrees to certain terms and conditions (expressly proposed in the bill), including, without limitation, that the user will not use the AI tool to promote illegal activity and (2) submit each “oath” (which is the term used in the bill) to the attorney general within in 30 days of the user making such oath.

States also proposed a variety of actions to provide them with insight into AI development and implementation. Louisiana (LA SB118) introduced a bill that would require "any person who makes publicly available within the state a foundation model or the use of a foundation model” to register with the secretary of state; this is similar to NY SB8214, which would require AI deployers to biennially register with the state. California SB1047 would require developers of large and complex AI models to determine whether their models have a “hazardous capability” and submit a certification to the state with the basis of their conclusion. Hawaii’s HB1607 requires certain deployers to conduct annual audits to determine whether the tools discriminate in any prohibitive manner.

Although only one bill in this category passed (UT SB149; see below), we anticipate states will continue to introduce bills with similar approaches and goals. Notably, these types of bills have the potential to impact a range of health stakeholders: payers and providers may need to submit specific information to states – operational lifts they will need to take into account when evaluating the potential benefits and risks of implementing AI tools into their systems. In addition, state health departments will need to determine how to absorb required audits and the review of submitted data – a significant lift for state health departments which are chronically under-resourced.

3. 11 states introduced legislation that included requirements to prohibit or address discrimination by AI tools (20 bills). Most bills in this category would prohibit the use of AI tools that result in discrimination, require deployers/developers to develop processes to avoid discrimination or bias, and/or mandate that deployers/developers summarize how they are managing against the risk of discrimination (e.g., OK HB3835, RI HB7521, VA HB747, VT HB710, WA HB1951, IL HB5116). A few states introduced language that would prohibit states from using discriminatory AI tools and/or require states to ensure tools are not discriminatory (e.g., NH HB1688, NY AB9149, OK HB3828). Oklahoma introduced language (OK HB3577) which would require payers to attest that training datasets minimized the risk of bias.

4. Only a small number of states introduced legislation on specific health care use cases, including provisions that impact insurance coverage determinations and access to services or the use of AI in clinical decision-making. Bills that propose to regulate AI use in the determination of insurance eligibility or medical necessity/prior authorization tended to specify that the determinations could not be based solely on the AI tool algorithm. For example, OK SB1975 states that “government, business, or any agent representing such shall not use AI and biotechnology applications to: […] determine who shall or shall not receive medical care or the level of such care; determine who shall or shall not receive insurance coverage or the amount of coverage”. CA SB1120 proposes to require that a “health care service plan shall ensure that a licensed physician supervises the use of artificial intelligence decisionmaking tools when those tools are used to inform decisions to approve, modify, or deny requests by providers for authorization prior to, or concurrent with, the provision of health care services to enrollees”. Other bills seemingly allow AI tools to make positive coverage and eligibility determinations but require a physician to review any decision that would negatively impact coverage or access to services (e.g., OK HB3577, NY AB9149).

Notably, there were a few bills that implicate the use of AI in clinical decision-making. As Manatt Health has previously summarized, Georgia’s HB887 proposes to require that AI-generated health care decisions be reviewed by an individual with “authority to override” the tools’ existing decision, and also requires the Medical Board to establish policies – including, but not limited to, disciplining physicians. Illinois’ SB2795 echoes a few bills introduced throughout 2023, which states that health care facilities may not substitute recommendations, decisions, or outputs made by AI for a nurse’s judgement, and that nurses may not be penalized for overriding an AI’s recommendations if, in the nurse’s judgement, it is in the patient’s best interest to do so.

5. Few health AI bills have passed. Of the nearly 90 bills introduced so far this year, only six bills have passed.

Utah passed the first state law on AI in the U.S., focusing on disclosures between the deployer and end user. Utah’s AI Policy Act places generative AI under its consumer protection authority, requiring that generative AI must comply with basic marketing and advertising regulations, as overseen by the Division of Consumer Protection of the Utah Department of Commerce

The law requires “regulated occupations”, which encompass over 30 different health care professions in Utah, ranging from physicians, surgeons, dentists, nurses, and pharmacists to midwives, dieticians, radiology techs, physical therapists, genetic counselors, and health facility managers to prominently disclose that they are using computer-driven responses before they begin using generative AI for any oral or electronic messaging with an end user. This likely means disclosures about generative AI cannot reside solely in the regulated entity’s terms of use or privacy notice. For more information on this Act, please see Manatt Health’s full summary here.

The five other bills that passed all established a task force or council to study AI:

- Florida SB7108: Establishes the "Health Care Innovation Council" to regularly convene subject matter experts to improve the quality and delivery of health care, including leveraging artificial intelligence. Council representatives include members across health care industry and ecosystem, and Council activities include: 1) developing and updating a set of best practice recommendations to lead and innovate in health care and focus areas to advance the delivery of health care and 2) recommending changes, including changes to law, to innovate and strengthen health care quality, among other duties.

- Washington SB5838: Establishes an AI task force to assess current use of AI and make recommendations to the legislature on possible guidelines and legislation. Health care and accessibility is one of several topics included in task force scope.

- West Virginia HB5690: Establishes the "West Virginia Task Force on Artificial Intelligence" to: 1) develop best practices for public sector use of AI, 2) recommend legislative protections for individual rights as relating AI, and 3) take an inventory of current or proposed use of AI by state agencies, among other duties. Task force membership must include the Secretary of Health or their designee and a member representing either the WV University Health System or Marshal Health Network

- Indiana SB150 and Oregon HB4153 do not expressly reference health care or health care stakeholders but may implicate the use of AI in health care in the future.

1 For a summary of key takeaways from Executive Order, please see here.

2 Health IT Certification Program, under which developers of health information technology (HIT) can seek to have their software certified as meeting certain criteria.

3 HTI-1 final rule defines predictive decision support interventions (Predictive DSI) as “technology that supports decision-making based on algorithms or models that derive relationships from training data and then produces an output that results in prediction, classification, recommendation, evaluation, or analysis.”

4 Note: A developer or deployer could include a state agency.

5 Note: Introduced bills may regulate more than one stakeholder, so the sum of these categories is greater than the total number of identified bills introduced. Additionally, “deployer” and “developer” are more general categories that could also include states, payers, providers, individuals, or other entities

6 Note: Introduced bills may regulate more than one activity. The sum of these categories is greater than the total number of identified bills introduced.

7 “‘Critical decision’ means any decision or judgment that has any legal, material, or similarly significant effect on an individual's life concerning access to, or the cost, terms, or availability of: […] family planning services, including, but not limited to, adoption services or reproductive services; […] health care, including, but not limited to, mental health care, dental care, or vision care; […] government benefits; or […] public services”

8 “Consequential decision” is defined as a “decision or judgement that has a legal, material, or similarly significant effect on an individual’s life relating to the impact of, access to, or the cost, terms, or availability of, any of the following: […] (5) family planning, including… reproductive services, … (6) healthcare or health insurance, including mental health care, dental, or vision”