Last week, the Federal Circuit reviewed the rare event of a preliminary injunction being granted in a lawsuit over a chemical invention, made rarer still by the evidence of likelihood of success on the merits required for the injunction being based on the doctrine of equivalents. And in the opinion, the panel took the opportunity to review the application of the doctrine to chemical arts cases, paradoxically but properly categorizing such application as being difficult in view of two of the leading cases on the doctrine (Graver Tank & Mfg. Co. v. Linde Air Prod. Co.; Warner-Jenkinson Co. v. Hilton Davis Chem. Co.) involving inventions in the chemical arts.

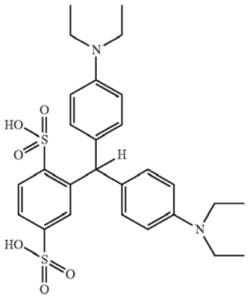

The case arose over a triarylmethylamine dye called isosulfan blue ("ISB") and methods for preparing it, used to map lymph nodes in a variety of diagnostic methods. The patents-in-suit -- U.S. Patent Nos. 7,622,992, 8,969,616, and 9,353,050 -- claimed methods for making the dye (the '992 and '616 patents) and purified compositions of the dye (the '050 patent) suitable for diagnostic reagent use. The patents are owned by Apicore and licensed exclusively by Mylan. Claims 1 of the '992 and '050 patents, respectively, are representative:

The '616 patent (emphasis added):

A process of preparing N-[4-[[4-(diethyl- amino)phenyl] (2,5-disulfophenyl)methylene]-2,5- cyclohexadien-1-ylidene]-N-ethylethanaminium, sodium salt comprising combining a suspension of isoleuco acid of the formula

in a polar solvent with silver oxide, recovering isosulfan blue acid, and treating the isosulfan blue acid with a sodium solution.

The '050 patent (emphasis in opinion):

A compound N-[4-[[4-(diethylamino)phenyl] (2,5- disulfophenyl) methylene]-2,5-cyclohexadien-1-ylidene]-N-ethylethanaminium, sodium salt having a purity of at least 99.0% by HPLC.

The dye was developed first by Hirsch Industries (according to the opinion) in 1981, which commercialized the product as a 1% solution sold as Lymphazurin®. A successor-in-interest to Hirsch, Coviden, owned the NDA for the product and marketed it despite problems with purity (being only 94.5% pure from the evidence of record below). The product was produced by Allied Chemical Co. and sold to Coviden by Sigma-Aldrich Co., but both the production method and purity of this product was "unknown," although record evidence established that Sigma needed to purify lead from the product, suggesting a lead compound was used in the synthesis. When Sigma stopped supplying the product in 2000, Coviden was forced to list is as "unavailable"; this situation only resolved in 2008 when Innovassynth became Sigma's supplier of a product made using ammonium dichromate (instead of silver oxide).

Apicore developed the inventions claimed in the patents-in-suit and its partner Synerx Pharma filed an ANDA that was approved in 2010; Mylan acquired Synerx in 2012. Coviden withdrew from the market in 2012 and Mylan was the sole provider of ISB until Aurobindo entered the marketplace in 2016.

Aurobindo filed its ANDA that contained an admission that it had "studied a 'number of patents' ISB manufacture and selected, inter alia, Apicore's '992 patent." It modified the production methods disclosed in the '992 patent by substituting manganese dioxide for silver oxide as recited in the '992 patent claims; this synthesis produced ISB that was only 90-95% pure, and the final product was purified to "greater than 99.5%" using preparative HPLC.

Mylan sued Aurobindo and the District Court entered a preliminary injunction based on all the patents-in-suit. As explained in the Federal Circuit opinion, the District Court's analysis of the four factors comprising the standard for granting a preliminary injunction (1) likelihood of success on the merits; 2) irreparable harm to the patentee; 3) balance of the hardships; and 4) public interest) were satisfied by Mylan. For the first prong of the test, the District Court found that Aurobindo was likely to have infringed the '992 and '616 patents under the doctrine of equivalents. The difference between the claimed method and Aurobindo's method was the use of manganese dichromate rather than silver oxide as claimed, and this difference was "irrelevant" using either the "function-way-result (FWR)" or "insubstantial differences" tests set out in Graver Tank. The District Court relied on expert testimony regarding the understanding of the skilled worker on the relative oxidation strengths of the compounds and the similarity on the purity yields using each reagent. With regard to validity, the District Court found that Aurobindo had not raised a substantial question of validity for the '050 patent, based on three arguments: "(1) under § 112 because the 'by HPLC' limitation renders the claims indefinite; (2) under § 103 because the claims would have been obvious over various combinations of art; and (3) under § 102 because the claims are anticipated by Sigma's manufacture and sale of ISB." The Court credited Mylan's expert regarding the conventionality and understanding in the art of the term "using HPLC" in deciding that Aurobindo had not raised a substantial question of indefiniteness against the '050 patent claims. The Court found that Aurobindo had not raised a substantial question of obviousness case against the '050 patent claims because "'a purified compound is not always prima facie obvious over the [prior art] mixture' if the process to arrive at the purified compound is itself of patentable weight," citing Aventis Pharma Deutschland GmbH v. Lupin, Ltd., 499 F.3d 1293, 1301 (Fed. Cir. 2007), and here the purification process recited in the '050 patent provided such patentable weight. In addition, the District Court credited Mylan's assertion of several secondary considerations of non-obviousness, particularly long-felt need, failure of others, and the admitted copying by Aurobindo. Finally, Sigma's prior manufacture and sale of ISB did not raise a substantial question of anticipation against the '050 claims, because the evidence did not establish that Sigma produced ISB having a purity of greater than 99%.

For the second prong, the District Court found Apicore would be irreparably harmed due to "lost sales; lost R&D; price erosion; and [direct competition] with an infringer." The District Court found a "causal nexus" for this harm because Aurobindo would not have been on the market without FDA approval and would not have obtained FDA approval without infringing Apicore's claims.

The balance of the equities prong likewise weighed in favor of Apicore and the public interest also favored granting a preliminary injunction because "the public interest in obtaining lower-priced pharmaceutical compounds cannot justify 'entirely eliminating the exclusionary rights covered by pharmaceutical patents.'"

The Federal Circuit affirmed in part and reversed in part, in an opinion by Judge Lourie joined by Judges Moore and Reyna (thus keeping the preliminary injunction in force). The opinion emphasizes that the standard of review is abuse of discretion and that the Court will defer to factual determinations by the District Court. Aurobindo's appeal of the injunction focused on three arguments: that the District Court erred in finding that its method of producing ISB infringed the '992 and '616 patents under the doctrine of equivalents; that it had not raised a substantial question of validity regarding the '050 patent; and that Apicore would suffer irreparable harm. Aurobindo did not challenge the District Court's findings on the balance of the hardships or public interest prongs of the preliminary injunction standard.

The issue of Mylan's likelihood of success on the merits, and its reliance in the doctrine of equivalents, gave the panel the opportunity to opine on the state of DOE law with regard to chemical inventions, and in doing so find that the District Court had erred in reaching its conclusion that Mylan would likely prevail on this issue. But it attributed this failure to "the sparse and confusing case law concerning equivalents, particularly the paucity of chemical equivalence case law, and the difficulty of applying the legal concepts to the facts." In attempting to bring clarity, the opinion starts with Graver Tank and sets out the two tests (FWR and insubstantial differences) arising from that Supreme Court decision. Concerning the application of the FWR test, the panel states that "[t]he Supreme Court was surely correct in stating that non-mechanical cases may not be well-suited to consideration under the FWR test" and that this "seems to be particularly true in the chemical arts" (despite it being applied in both Graver Tank and Warner-Jenkinson, both chemical cases). Here, the District Court applied the FWR test, and the opinion characterizes this application as being "flawed by being unduly truncated and hence incomplete." Specifically, the panel criticized how the District Court applied the FWR test limitation by limitation to the elements of the accused infringing process, saying that "it is often not clear what the 'function' or 'way' is for each claim limitation," particularly with regard to activities in corpora. The result, on the other hand, of a process claim is typically more readily assessed, in the panel's opinion, as frequently being clear: "why else would a claim for infringement of a process claim be brought if the claimed result is not obtained?" But the "function" and "way" prongs of the test can overlap and cause error, which is what the panel concludes occurred before the District Court. The difficulty, in the Federal Circuit's view, is that the District Court did not consider with regard to the "way" prong the differences between using silver oxide and manganese dioxide. As set forth in the District Court's opinion, these oxidizing agents were assessed for DOE purposes as being related to the "function" prong, so that the Court could dismiss Aurobindo's arguments regarding differences in oxidation strength as being irrelevant (since both compounds oxidized the precursor to the final ISB product). However, "[m]anganese dioxide and silver oxide may have the same function, but the question is whether they operate in the same way," according to the opinion (emphasis in opinion). Moreover, there was language in the District Court's opinion indicating that differences in oxidation strength raised a question of claim construction not before the Court. The Federal Circuit found error in this analysis of the "way" prong sufficient to reverse the District Court's finding of Mylan having established a likelihood of success at prevailing in establishing infringement under the doctrine of equivalents.

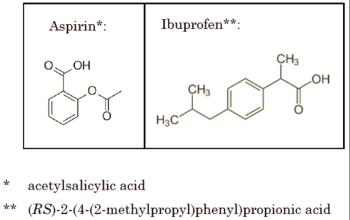

The opinion, no doubt in an effort to clarify the application of the doctrine in chemical cases, suggests that the District Court should more profitably consider using the "insubstantial differences" test, using aspirin and ibuprofen to illustrate structural differences sufficient to fail the insubstantial differences test:

but sufficient similarities to pass the FWR test:

They each provide analgesia and anti-inflammatory activity ("function") by inhibiting prostaglandin synthesis ("way") in order to alleviate pain, reduce fevers, and lessen inflammation ("result").

The opinion suggests the District Court review the equivalents question at trial using the insubstantial differences test as perhaps being more appropriate in chemical cases, particularly because:

Manganese dioxide and silver oxide are substantially different in many respects. For example, manganese and silver are in different groups of the Periodic Table. In oxide form, manganese has an oxidation state of +4, while silver is +1. Those differences may well be relevant to equivalence at trial. Thus, the choice of test under the doctrine of equivalents may matter in this case.

In its review of the propriety of granting a preliminary injunction over the '050 patent, the Federal Circuit considered whether the District Court's determination that Aurobindo had not raised a substantial question of patentability on the three asserted grounds. The panel found no assertion by Aurobindo of legal error by the District Court, relying on a purported "misreading of the factual evidence." However this basis for arguing error it fatally flawed because the Federal Circuit defers to factual finding of the District Court and requires Aurobindo to demonstrate clear error by the Court. This the defendant did not do. The opinion finds no error in the Court's assessment of the facts regarding anticipation, based on the lack of evidence that Sigma produced ISB having the claimed purity. Similarly there was no clear error by the District Court in finding Aurobindo had not raised a substantial question of obviousness against the '050 patent claims, stating that "[i]t is clear from the record here that, although ISB was known in the prior art, the path to arrive at ISB with a purity of greater than 99.0% was not known before the relevant date of the '050 patent." Moreover, the panel held that Mylan's evidence regarding secondary considerations established that "prior to the '050 patent's relevant date, a reliable source of high-purity ISB was so scarce that, at one point, Coviden was forced to notify its customers that it was "completely out of" Lymphazurin® until it could find a new supplier for ISB." Finally, the opinion concludes that there was no clear error in finding that reciting "using HPLC" would have been indefinite to the skilled worker, a conclusion the Court appreciates even Aurobindo's expert to have admitted.

The opinion concludes with a review of the District Court's finding that Apicore would suffer irreparable harm, based inter alia on the argument that the patented features of the inventions claimed in the patents in suit were irrelevant to Mylan's marketing the product. The Federal Circuit finds ample evidence in the record supporting the District Court's conclusion that:

"(1) due to Aurobindo's infringement, Apicore has, and will continue to, suffer from lost sales, lost research and development, price erosion, and having to directly compete with an infringer []; (2) there was a causal nexus between Aurobindo's infringement and Apicore's harm because Aurobindo's product "would not be on the market if [it] had not obtained [FDA] approval for a product that will likely be found to be covered by the patents"[]; and (3) "[w]ithout infringing the [process and purity] patents, Aurobindo would not be able to make the [ISB] product described in its ANDA" (based in large part on Aurobindo's admissions).

Mylan Institutional LLC v. Aurobindo Pharma Ltd. (Fed. Cir. 2017)

Panel: Circuit Judges Lourie, Moore, and Reyna

Opinion by Circuit Judge Lourie