The combination of judicial trends and concerted executive branch action is expected to drive significant changes in the federal bureaucracy and affect financial services regulation

We have previously analyzed the recent history of Executive Orders ("EOs") controlling the issuance and content of regulations. As we saw on Inauguration Day 2025, and continue to see, the second Trump Administration is aggressively deploying EOs toward that end and others.

This note assesses those efforts as they affect the financial services industry, but also goes beyond the perimeter of EOs to explore how:

- recent changes in judicial interpretation of regulatory discretion (including the need for clear congressional delegation of power)

- the advent of new personnel in senior leadership of financial regulatory agencies

- shrinking the size of the federal government

are expected to change how the federal bureaucracy functions in connection with the oversight of the financial services industry.[1]

A New and Experienced Administration

We expect a shorter learning curve for the second Trump Administration. At the outset of the first Trump Administration, new executive branch political staff were in many ways unfamiliar with the operations of the federal government, both formal and informal. They got off to a slow start and became preoccupied with various scandals and a burst of litigation, and had limited time to focus on deep regulatory reform. This time, President Trump is re-entering office for a nonconsecutive second term (the first time since 1893) and many White House and agency staff are experienced and expected to execute their objectives as incumbents.

While the first Trump Administration was highly successful in cutting regulations,[2] it left much to be done and many EOs that might have led to more serious reform were adopted too late in the administration to have any meaningful impact. Since that time, however, the Supreme Court has significantly limited regulatory discretion by overturning the Chevron doctrine[3] and through the use of tools such as the Major Questions Doctrine.[4] Even without a new administration, these judicial developments have limited the ability of federal agencies to adopt regulations without clear authorization from Congress.[5] With new heads at OMB, OIRA,[6] OPM, and SEC, and anticipated changes at the federal banking agencies, we expect an aggressive effort over the next twelve months to accelerate implementation of (and curb resistance to) the new deregulatory agenda.

The confluence of all these elements may result in changes to regulatory administration that are faster and deeper than would normally be expected with the advent of a new administration.

Executive Orders

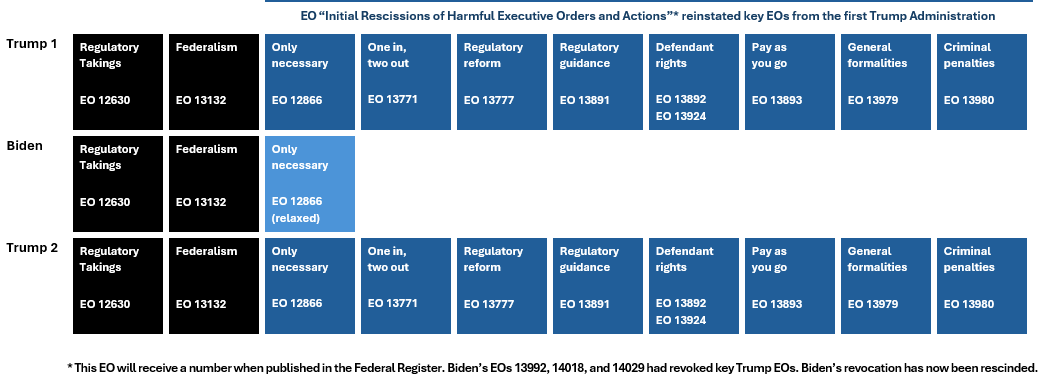

Most of the EOs from the first Trump Administration limiting the regulatory state were reinstated with President Trump's "Initial Rescissions of Harmful Executive Orders and Actions" EO, signed on January 20, 2025. In particular, EOs 13771, 13893 and 13979 required more thorough review of proposed regulations[7] and EO 13777 created Regulatory Reform Officers and Regulatory Task Forces within each agency. Unlike the first Trump Administration, where in many cases these offices were never fully staffed, one can expect that they will be staffed and will begin their work in the very near future.

Click to enlarge.

Applying Regulatory Standards to Independent Agencies

Federal financial regulators, such as the Federal Reserve and the FDIC, are considered independent. In the past, this independence has insulated them to a degree from Executive Branch pressure.

However, on October 8, 2019, the U.S. Department of Justice's Office of Legal Counsel ("OLC") issued a Memorandum Opinion for the Counsel to the President ("OLC Opinion") that concluded that the President could apply previous EOs, such as EO 12866 ("Regulatory Planning and Review"),[8] to independent agencies and use those EOs to govern their administrative programs and agendas. It stated plainly that the President "may direct independent regulatory agencies to comply with the centralized regulatory review process prescribed by Executive Order 12866."[9] The OLC also explained: "the President has the 'distinctive constitutional role' of supervising the execution of federal law, and he could not take care that the entire 'mass of legislation' is executed faithfully, in a consistent and uniform manner, absent authority to guide and direct his subordinates."[10] And, while Congress has placed some limits on the President's authority when dealing with independent agencies, such limits "do not preclude the President from requiring the agencies to comply with EO 12866."[11]

We expect that the soon-to-be-appointed heads of the federal banking agencies will adopt policies consistent with the OLC Opinion.

Notably, the OLC Opinion also discussed the ability of the President to remove senior agency officials who exercise executive powers, noting that the Supreme Court "has confirmed that the president must have some constitutional authority to remove all those executive officers whom he appoints, including the heads of independent agencies."[12] As events unfolded, the OLC Opinion was something of a precursor to developments regarding presidential power at the Supreme Court.

Recent Article II Jurisprudence: Is "Independence" A Shield?

Recent Supreme Court opinions have assisted in the expansion of presidential power to oversee executive branch agencies. Besides the limitation on agency discretion announced in Loper Bright[13] and the more frequent use of the Major Questions Doctrine, requiring agencies to go to Congress if they seek additional regulatory authority,[14] three recent Supreme Court opinions[15] have laid the groundwork for a more liberal usage of the presidential removal power with respect to principal and inferior officers of agencies who exercise executive powers. In a recent Cornell Law Review article regarding Article II powers, Professors Aditya Bamzai (Virginia Law) and Aaron Nielson (BYU Law) wrote, regarding the independence of the Federal Reserve Board and the ability of the President to remove the Chair and Vice Chairs:

In Collins, however, the Court explained that labeling an agency 'independent' 'does not necessarily mean the agency is independent of the President.' Instead, the term can be read to mean 'that the Agency is not part of and is therefore independent of any other unit of the Federal Government.' Indeed, Collins stressed that Congress sometimes calls agencies 'independent' but does not intend to impose any restrictions on removal. Accordingly, just because Congress has labeled an agency 'independent' does not necessarily mean that the president cannot fire the agency's head.[16]

Notably, the Harvard Law Review also recently published an article by Professors Bamzai and Saikrishna Bangalore Prakash (Virginia Law) based on new materials from the Founding and early practice that defend the Madisonian view that "executive power" encompasses authority to remove executive officials at pleasure.[17] Focusing on the debates at the Constitutional Convention and in the First Congress, they observe:

[I]f the removal power follows the appointments power [which Constitutionally rests with the President alone], the President has a power to remove at pleasure and can exercise it independent of the will of the Senate or Congress. Further, some advocates of Presidential removal said that the Chief Executive could not ensure a faithful execution of the laws if he could not remove unfaithful officers. These arguments were secondary to the principal point that the executive power conveyed a removal power.[18]

Given that one of the stated goals of the second Trump Administration is to control the federal bureaucracy, these interpretations validating a broad exercise of executive power are likely to be closely considered by agency leaders and their senior legal advisers.

Personnel Is Policy

The new administration has appointed a series of agency heads and executives who are likely to have a reform-minded agenda with respect to agency discretion. We expect that this new leadership will bring an end to a "regulation-by-enforcement" approach and anti-crypto efforts, such as "Operation Chokepoint 2.0," at different federal financial regulators.

In addition, the appointment of James Sherk, who has written extensively about federal personnel management and analyzed past bureaucratic reaction to Executive Branch change,[19] to the White House Domestic Policy Office and the naming of Sergio Gor to run the White House's Presidential Personnel Office, which supervises the nominations of all Article II appointees who must be confirmed by the Senate, signals an intent by the second Trump Administration to put forth appointees who have a similarly aligned view of extensive executive power and will take a dim view of a wide breadth of agency independence and discretion. In a similar vein, the naming of Andreessen Horowitz partner Scott Kupor to head the Office of Personnel Management ("OPM") indicate a likely tech-forward approach.[20]

Schedule F – Its Contents and Potential Impact

A controversial reform that was adopted, but never implemented, in the first Trump Administration was the addition of "Schedule F" to the OPM policy and standards. It was reinstated by EO on January 20, 2025.

Schedule F may be seen as the logical outgrowth of the authorities cited above. It is statutorily rooted in 5 U.S.C. § 7511(b)(2), which provides the President with authority to exempt policy-influencing positions from civil service appeals. It also stands for the principle that certain senior federal career officials (not confirmed by the Senate) who perform policy-making roles should not be subject to civil service protections on removal, thus making them more easily replaceable by senior political appointees if they perceive that these officials on Schedule F are not performing up to standard or are not fulfilling the agency's agenda.

In a prior publication, Sherk described the need for Schedule F this way:

Executive Order 13957 [which created Schedule F] gave agencies greater flexibility in hiring, and eliminated appeals when dismissing federal employees in senior policy-influencing positions. The order also retained protections against politically motivated or otherwise discriminatory dismissals. [Schedule F] would have given agencies greater discretion in hiring and firing senior career officials, while retaining their status as career employees based on merit.[21]

Schedule F applies to approximately 50,000 individuals (out of a total civilian federal workforce of approximately 2.2 million) and, as Sherk noted, would be used only on those occasions where an individual exhibited a significant lack of performance or cooperation. Sherk emphasized that the vast majority of senior federal executives were neutral and collaborated in good faith with the first Trump Administration. However, the newly reinstated Schedule F is likely to give senior agency officials significantly more latitude to form (or reform) their own teams who are committed to the implementation of the second Trump Administration's agenda.

Conclusion

It would be a mistake to expect that the federal regulatory state will not change during the second Trump Administration. The transition seems to indicate that senior administration staff are focused on employing effective tools and processes to ensure that they have in place senior agency career leaders who will collaborate in the implementation of regulatory reform.

Moreover, there will be pressure to implement these policies arising out of recommendations from the Department of Government Efficiency, which will implement its findings through OMB.[22] At the same time, regulators who wish to adopt new rules will find that OIRA will raise the bar as to the analysis required for the new rulemaking and insist on assurances that the proposed rulemaking is within the powers delegated to the agency by Congress.

On balance, given the forces at play—including a more favorable legal environment and a more internal organization—the second Trump Administration is likely to pursue a smaller federal workforce, focus more on senior level analysis, and commit to more regulatory reform, not least of all in financial regulation.

[1] Many of those changes have already begun, starting with the announcement of the FDIC's new priorities and the SEC's crypto task force.

[2] Council of Economic Advisers, President Trump's Regulatory Relief Helps All Americans, White House (July 16, 2020).

[3] Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo, 603 U.S. 369 (2024).

[4] See, e.g., Biden v. Nebraska, 600 U.S. 477 (2023); West Virginia v. EPA, 597 U.S. 697 (2022).

[5] See, e.g., Alabama Ass'n of Realtors v. HHS, 594 U.S. 758 (2021) (explaining that an agency must operate within the bounds of its statutory authority).

[6] The Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs ("OIRA"), within OMB, can play a constricting function related to newly proposed regulations. If OIRA believes an agency should reconsider a proposed action it may return the proposal with a written explanation for the return.

[7] These executive orders were consistent with the purpose of President Clinton's foundational EO 12866, which set standards for the implementation of regulation. Among other things, EO 12866 noted: "Federal agencies should promulgate only such regulations as are required by law, are necessary to interpret the law, or are made necessary by compelling public need …." (Emphasis added.).

[8] The key points of EO 12866 are that it (1) provides for a centralized review of regulations; (2) requires regulatory planning by agencies; (3) calls for cost/benefit analyses; (4) requires a Regulatory Impact Analysis ("RIA") for economically significant regulatory actions; and (5) allows OIRA to return a draft rule to the agency for further consideration of some or all of its provisions. RIAs are conducted under OMB Circular A-4 which requires agencies to clearly identify why regulation is needed, whether it considered a reasonable number of alternative regulatory approaches, and to conduct for each alternative a rigorous and objective cost benefit analysis. RIAs are reviewed by OIRA for transparency, utility, and objectivity. EO 12866 was modified on April 6, 2023, by EO 14094 ("Modernizing Regulatory Review"). However, EO 14094 was rescinded on January 20, 2025.

[9] Extending Regulatory Review Under Executive Order 12866 to Independent Regulatory Agencies, 43 Opinions of the Office of Legal Counsel of the U.S. Dep't of Justice 232 (Oct. 8, 2019).

[10] Id. at 240.

[11] Id. at 244. The OLC also noted that "The President may require any agency to submit in writing an analysis of proposed agency action under the Opinions Clause, which authorizes the President to 'require [an] Opinion, in writing,' from the principal officers in the Executive Branch on 'any Subject' relating to 'the duties of their … offices.' U.S. Const. art. II, § 2, cl. 1." Id. at 241.

[12] Id. at 245.

[13] See Loper Bright, 603 U.S. 369.

[14] See Nebraska, 600 U.S. 477; West Virginia, 597 U.S. 697.

[15] See Collins v. Yellen, 594 U.S. 220 (2021); Selia Law v. CFPB, 591 U.S. 197 (2020); Free Enter. Fund v. Public Co. Acct. Oversight Bd., 561 U.S. 477 (2010).

[16] Aditya Bamzai & Aaron L. Nielson, Article II and the Federal Reserve, 109 Cornell L. Rev. 843, 889 (2024).

[17] Aditya Bamzai & S.B. Prakash, The Executive Powers of Removal, 136 Harv. Law Review 1756 (2023).

[18] Id. at 1775. The authors contend that the President "has an executive power to remove executive officers at pleasure." Id. at 1837. They argue that the Constitution implicitly constrains the President's removal power by way of the vow to faithfully execute his office, which, in the minds of the authors, implies that the President "owes the nation a duty of loyalty, care and trust" that must attend to the exercise of the removal power. Id; see also, Brian D. Feinstein & Jennifer Nou, Submerged Independent Agencies, 171 U. Penn. L. Rev. 945, 997-1007 (2023). Nonetheless, the academic debate over the extent of Article II powers continues. In reply to Professors Bamzai and Prakash, Professors Andrea Katz (Washington University) and Noah Rosenblum (NYU) published "Removal Rehashed," 136 Harv. L. Rev. 404 (2023), and in response to their critique, Professors Bamzai and Prakash published "How To Think About The Removal Power," 110 Va. L. Rev. (Online) 156 (2024). This energy is likely to surface in the political and judicial worlds in the near future.

[19] See, e.g., James Sherk, Tales from the Swamp: How Federal Bureaucrats Resisted President Trump, America First Policy Institute (Feb. 1, 2022; updated Jan. 8, 2025).

[20] See, e.g., "Ending Illegal Discrimination and Restoring Merit-Based Opportunity" (Jan. 21, 2025).

[21] James Sherk, AFPI Comment on Proposed Office of Personnel Management Regulation That Would Prevent Reinstatement of Schedule F, America First Policy Institute (Nov. 21, 2023).

[22] While less likely, "sue and settle" tactics (much decried during the Obama Administration) could be deployed to drive additional change where normal processes prove inadequate. See Daniel E. Walters, New "Sue-and-Settle" Bill is Much Ado About Nothing, The Regul. Rev. (Mar. 24, 2015).

[View source.]