[author: Kevin E. Noonan]

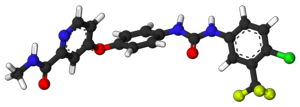

In response to an earlier post on Novartis' challenge to the Indian Patent Office's decision not to grant a patent on its anticancer drug Gleevec® (see "Indian Supreme Court to Rule on Gleevec Patent"), a reader opined that we should appreciate the erudition and wisdom of the patent official in Mumbai responsible for the denial. He helpfully sent along the decision granting a compulsory license to Natco for Bayer's anticancer drug, sorafenib tosylate (sold as Nexavar®). A review of the decision indeed provides insights into how officials in India interpret the provisions of its law regarding compulsory licenses. Such a review also suggests that what may appear to produce a "Catch 22" for Western drug companies can reasonably be considered to be a straightforward application of sound principles in the best interests of the Indian citizenry.

The provision of Indian law at issue is Section 84 of the Patent Act:

84. Compulsory licenses. –

(1) At any time after the expiration of three years from the date of the grant of a patent, any person interested may make an application to the Controller for grant of a compulsory license on patent on any of the following grounds, namely –

(a) that the reasonable requirements of the public with respect to the patented invention have not been satisfied . . .

. . .

(ii) the demand for the patented article has not been met to an adequate extent or on reasonable terms . . .

(b) that the patented invention is not available to the public at a reasonably affordable price . . .

(c) that the patented invention is not worked in the territory of India.

With regard to this requirement, the Indian Controller of Patents set out the competing claims of the compulsory license applicant and the patentee. The applicant alleged that there were ~20,000 liver cancer patients and ~9,000 kidney cancer patients (the populations that benefit from the drug), and that assuming 80% demand there would be a need for about 23,000 bottles of the drug per month to satisfy the demand. The facts (albeit disputed by Bayer) presented showed no bottles imported into India in 2008, ~200 bottles in 2009 and that there was no evidence for import in 2010. The significance of these dates and amounts are that the Indian government granted Bayer a patent on the active pharmaceutical ingredient in Nexavar® in 2008, and the Controller assessed Bayer's behavior in fulfilling the "reasonable requirements of the public" during that time. It was also significant that Bayer did not produce the drug in India, explaining the focus on bottles of imported drug. The Controller's decision mentions that failure to manufacture the drug in India was evidence that Bayer had not "taken adequate steps to . . . make full use of the invention."

In addition, and in what is the crux of the matter, the Controller stated that the drug is exorbitantly priced and out or reach of most of the people. The price of the patented drug was quoted in the decision as being Rs.2,80,248/- per month and Rs.33,65,136/- per year, as opposed to the price of Rs.8800/- per month from Natco. In addition, the Controller stated that while the drug might be available in metropolitan areas (such as Mumbai, Delhi, Chennai and Kolkata) it was not available throughout the country. Even then the Controller said that the drug was frequently in short supply even in cities and that this was significant because it is a "life saving drug" and not a "luxury item." Finally, the Controller noted that Bayer's worldwide sales increased from $165M in 2006 to $934M in 2010. "These figures clearly demonstrate the neglectful conduct of the Patentee as far as India is concerned," he writes.

The Controller also disregarded Bayer's argument that sales of another Indian generic company, Cipla, should be taken into account in determining whether the Indian market was being reasonably satisfied, noting that Bayer had sued Cipla in Delhi and asked for an injunction to stop these infringing sales. (In this regard, later in the decision the Controller characterizes this argument as "indulging in two-facedness" and "defend[ing] the indefensible.") In so doing, the Controller also enunciated an Indian-centric philosophy, stating that "the mandate of law is not just to supply the drug in the market but to make it available in a manner such that substantial portion of the public is able to reap the benefits of the invention" and that "[i]f the terms are unreasonable such as high cost of nRS.2,80,000/-, availability is meaningless." (This aspect of the decision was illustrated by the Controller's calculation that, at Bayer's prices it would take the "common man" (the lowest-paid government worker) 3.5 years' wages to afford one month's supply of the drug, but Nexavar extends life for the kidney cancer patient by only 4-6 years and the liver cancer patient by only 6-8 months.) In coming to these determinations, the Controller cited a Bulletin from the World Health Organization; a research article on the "impoverishing effects" of the affordability of medicines in the developing world from PLoS; and an affidavit from James Packard Love, Director of Knowledge Ecology International and co-chair of the Trans-Atlantic Consumer Dialog Policy Committee on Intellectual Property Rights. (Perhaps) needless to say, these sources did not support Bayer's petition that the Indian government deny a compulsory license to Natco.

For its part, Bayer made the patently correct argument that the cost of drugs supports the pipeline of future drug development and that Bayer "continued to invest major sums into further development of Sorafenib" for treating other cancer types. Bayer also noted that its investment in new drug development amounted to 8 billion Euros from 2007 to date, and that it takes more than 2 million Euros to bring a new drug to market. Further research is in the public interest, and granting Natco a compulsory license would harm the pubic interest in this regard. In what appears to be an effort to avoid a complete defeat, Bayer also argued that a compulsory license should not benefit those in India ("the Rich class" and "the middle class") who could afford the drug at Bayer's price in an attempt to provide the drug to the "common man" who could not (supporting this argument with affidavits from representatives of the Indian medical and insurance industries). (The Controller does not reject this argument but questions why Bayer had not instituted such a graduated pricing regime itself.) But this varying level of the ability to pay, with the varying effects on the question of whether the price was "reasonably affordable" should be sufficient, Bayer argued, to preclude grant of a compulsory license to Natco, since it is a "sine qua non" (or "condition precedent") for a compulsory license that a drug not be available at a "reasonably avoidable price" (although this argument suffered from the fact that the availability of Nexavar® at a "reasonably affordable price" was dependent on sales by Cipla).

The Controller's decision, in favor of granting a compulsory license, was based on his determination that the question of whether a drug was available at a "reasonably affordable price has to be construed predominantly with reference to the public" and under the "admitted facts" of this case these considerations fell in favor of granting the license.

Finally, the Controller looked at the fact that Bayer did not "work" the invention in India. Here, the law was construed with regard to whether the invention was worked "to the fullest extent possible" and here it clearly was not (upon evidence that Bayer had "worked" the patented invention "extensively" in other countries while having the industrial capacity to work the patent, i.e., produce Nexavar®, in india). "Minimal" working is not enough, according to Natco, while Bayer argued that the extent of working a patented invention depends on the invention and, for Nexavar® the "small global demand" justifies the "strategic decision" to make the drug in Germany.

In making his decision, the Controller noted that the term "worked in the territory of India" had not been defined in the Indian Patent Act, and so he needed to construe the term with regard to "various International Conventions and Agreements in intellectual property," the 1970 Patent Act and the legislative history. But the Controller seemed more interested in addressing the "crucial argument" of the patentee that the applicant's construction of the term was incorrect because the phrase "default of the patentee to manufacture in India to an adequate extent and supply on reasonable terms the patented article" was deleted from the Act. He decided that this was "one face of the coin," but that the other was that the phrase was deleted from Section 84(1)(a) with regard to the patented article being "reasonable available to the public" in favor of Section 84(1)(c) which "was made a separate ground for grant of a compulsory license."

In this light, the Controller considered the relevant provisions of the Paris Convention, the TRIPS agreement and the Indian Patents Act of 1970 and decided that the combination of Article 27(1) of TRIPS and Article 5(1)(A) of the Paris Convention supported an interpretation that failure to manufacture Nexavar® in India supported the grant of a compulsory license to Natco (which it termed "reasonable fetter" on Bayer's patent rights). Ultimately, however, the Controller finds ample justification for the compulsory license in Section 83(b) of the Patent Act, which states that "[p]atents are not granted merely to enable patentees to enjoy a monopoly for importation of the patented article" and Section 83(c) that "the grant of a patent right must contribute to the promotion of technological innovation and to the transfer and dissemination of technology." Coupled with the provisions of Section 83(f) that a patent should not be abused, the Controller construes Indian patent law to require that a patentee work a patented invention in India or license another do to so.

After refusing to adjourn the proceedings based on Section 86 of the law (finding, inter alia, that Bayer had not established any justifiable reason for its "delay" in working the patent in India), the Controller established the terms of the compulsory license, wherein:

i. the right to make and sell sorafenib limited to applicant (no sublicensing)

ii. the compulsorily licensed drug product can be sold only for treatment of liver and renal cancer;

iii. the royalty shall be paid at a rate of 6%

iv. the price set at Rs.74/- per tablet, which equals Rs. 8,800/- per month;

v. the applicant commits to provide the drug for free to at least 600 "needy and deserving" patients per year

vi. Compulsory licend not assignable and non-exclusive, with no right to import the drug

vii. No right for the licensee to "represent publicly or privately" that its product is te same as Bayer's Nexavar®

viii. Bayer has no liability for Natco's drug product, which must be physically distinct from Bayer's dosage form

The license was granted on March 9, 2012.

What lessons can be learned from Bayer's experience? Some seem self-evident: patents granted in India come encumbered with a responsibility to produce the patented article in India, either by the patentee itself or by licensing a local Indian company. Second, political realities and economics, particularly for drugs, require some mechanism for providing drugs to those who genuinely cannot afford them. Third, these efforts must be both effective and public; token efforts, specifically efforts that supply much less than the actual demand, will be deemed insufficient. Finally, by licensing rather than being forced to license, patentees can negotiate (perhaps with more than one local company) rather than having the Patent Controller decide the terms (and those terms can be kept confidential). While the Controller here was careful to craft the license to prevent the licensee from exporting the drug, not all compulsory licensees will necessarily be so limited, an important consideration in view of the risks attendant on a licensed competitor being able to supply the global market. Finally, the lesson is again learned that foreign drug companies are no match for local drug manufacturers who promise to provide drugs at affordable prices to citizens of India who could not otherwise afford them. In view of the near certainty that licenses under these circumstances will be granted, it behooves Western drug companies to take the initiative to avoid the outcome Bayer suffered last week.