It is a certainty that no matter what action is taken (by an individual, a group, or especially a legislative body) that there will be unintended consequences. It is also true that those unintended consequences, like the exception that probes the rule, will illustrate the extent to which the decision-maker misunderstood or misconstrued the "problem" that the action was intended to solve (primarily by the nature of the problem(s) the solution creates).

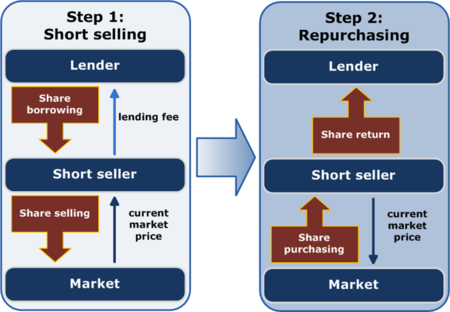

One such unintended consequence of the decision by Congress to add to the post-grant reexamination provisions in the 2011 Leahy-Smith America Invents Act, and specifically the inter partes review provisions before the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB), has recently come to light. Specifically, at least one hedge fund manager has decided to file inter partes review petitions against patents owned by pharmaceutical companies and listed in the Orange Book to protect drug products under the Hatch-Waxman Act (the 1984 Drug Price and Patent Term Restoration Act). While ostensibly to address "BS" patents that cause drug prices to be "too high," at the same time the strategy includes "shorting" the drug company's stock and profiting when the stock price lessens in response to the IPR filing:

While there appears to be nothing illegal about this practice (for example, there is no apparent violation of insider trading or other securities laws), only the most rabid patent critic would approve of this use of the patent system to manipulate the value of a private company's stock.

And the blame for the situation does not lie (entirely) at the feet of the financial sector or its agents; rather, the reason the opportunity for this strategy exists is the law itself, prompted by the conviction that the Patent and Trademark Office (PTO) had been granting "bad" patents that were being used by "trolls" (otherwise known as patent-holders) to retard innovation (by preventing big companies from expropriating patented technology from smaller companies, universities and sole inventors). The problem was presented as being so pernicious and so in need of remedy that the ability to institute inter partes review was made available to anyone (except the patent holder, which was more a practical consideration than a handicap) throughout the unexpired term of a patent. (Curiously, Congress recognized how to limit the scope of the right to file for reconsideration before the PTO, for example, in the covered business method patent review process, which is only open to challengers who have been accused of infringement: "A person may not file a petition for a transitional proceeding with respect to a covered business-method patent unless the person or his real party in interest has been sued for infringement of the patent or has been charged with infringement under that patent.")

What is missing, of course, is a requirement for standing. Standing is always an issue in district court litigation, in contrast, and generally courts have required that plaintiffs satisfy the standing requirements in order to withstand a Rule 12 motion to dismiss a complaint. In the Myriad litigation, for example, the Federal Circuit held that the majority of the named plaintiffs (the women breast cancer sufferers, the medical and pathologist organizations, and almost all of the medical researchers) did not have standing. Indeed, the case might have been dismissed at the appellate level (and the question presented to the Supreme Court limited to standing) if not for Dr. Harry Ostrer, who averred that he would immediately provide BRCA testing if the patent bar was lifted (see "Federal Circuit Declines Invitation to Reconsider Standing Question"). This was enough for the court to recognize him as having standing to sue and thus for the Federal Circuit to have jurisdiction to decide the appeal. (Myriad attempted to derail this decision by challenging Dr. Ostrer's ability to provide testing when he moved from New York University to Montefiore Hospital, but this challenge was not addressed by the court.) And even earlier in the litigation, District Court Judge Sweet needed to rely on the ACLU's First and Fourteenth Amendment challenges against the PTO to avoid holding that the plaintiffs did not have standing.

Similarly, the Federal Circuit dismissed on standing grounds an appeal of the PTAB's decision in the inter partes reexamination brought by the Public Patent Foundation (PubPat) that upheld the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation's (WARF) patents on human embryonic stem cells (see "Consumer Watchdog v. Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation (Fed. Cir. 2014)"). The basis for this decision was that PubPat could aver no injury in fact because it was not an academic or commercial laboratory that could state that it would begin using WARF's patented stem cell technology if the Court reversed the PTAB's decision that the challenged claims were non-obvious.

Public interest challenges against particular patents have generally failed on standing grounds; for example, the ability of the PTO to grant patents on non-human genetically modified organisms (such as the Harvard Oncomouse) was challenged in district court by a collection of public interest groups including the Animal Legal Defense Fund, the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, People For The Ethical Treatment of Animals, and other animal rights groups in Animal Legal Defense Fund v. Quigg (Fed. Cir. 1991). The district court dismissed for failure to state a claim under the Administrative Procedures Act (APA) and Fed. R. Civ. Pro. 12(b)(6) and the Federal Circuit affirmed, but on the grounds that the plaintiffs did not have standing. Specifically, the Court held that the plaintiffs were not within the "zone of interest" relevant to patent law and thus could not establish standing. That case provides a succinct summary of the jurisprudential considerations at issue:

To establish standing to sue, as Article III has been interpreted, a party must, "at an irreducible minimum," show (1) "that he personally has suffered some actual or threatened injury as a result of the putatively illegal conduct" (personal injury), (2) that "the injury 'fairly can be traced to the challenged action'" (causation), and (3) that the injury "is likely to be redressed by a favorable decision" (effective relief). Valley Forge Christian College v. Americans United for Separation of Church and State, Inc., 454 U.S. 464, 472, 70 L. Ed. 2d 700, 102 S. Ct. 752 (1982)

In addition to these requirements for standing, the Supreme Court has further limited standing to those parties within the "zone of interests" a particular statute addresses. Air Courier Conference of America v. American Postal Workers Union, 498 U.S. 517, 112 L. Ed. 2d 1125, 111 S. Ct. 913, 59 U.S.L.W. 4140, 4142 (1991).

In affirming dismissal of the plaintiffs' suit, the Federal Circuit noted that plaintiffs claimed that "the general public has an interest in the statutory limitations to patentability." But the court found "nothing in the law which gives rise to a right in nonapplicants to object to the way in which patent applications of others are prosecuted. A third party has no right to intervene in the prosecution of a particular patent application to prevent issuance of an allegedly invalid patent," citing Chicago Rawhide Mfg. Co. v. Crane Packing Co., 523 F.2d 452, 458 n.13, 187 U.S.P.Q. 540, 545-46 n.13 (7th Cir. 1975), cert. denied, 423 U.S. 1091, 188 U.S.P.Q. 480, 47 L. Ed. 2d 103, 96 S. Ct. 887 (1976); Williams Mfg. Co. v. United Shoe Mach. Corp., 121 F.2d 273, 277, 50 U.S.P.Q. 264, 269 (6th Cir. 1941), aff'd, 316 U.S. 364, 86 L. Ed. 1537, 62 S. Ct. 1179 (1942); Godtfredson v. Banner, 503 F. Supp. 642, 646, 207 U.S.P.Q. 202, 207 (D.D.C. 1980); see also Syntex v. United States Patent and Trademark Office, 882 F.2d 1570, 1574-75, 11 U.S.P.Q.2d 1866, 1870 (Fed. Cir. 1989). There are clear parallels to this case and Myriad; for example, in addition to the public interest plaintiffs individual farmers and farmer groups also joined in the suit.

Congress saw fit not to include a standing requirement in the inter partes review provisions of the AIA, consistent with the "torches and pitchforks" attitude certain interest groups encouraged (and continue to encourage) against a patentee asserting a presumptively valid patent against them. As a consequence (unintended or not) the law creates opportunities for financial shenanigans unappreciated when the bill was being considered. Having seen the error of its ways in this regard, it should be obvious that it is up to Congress to remedy the situation. Patent reform is one of the bipartisan buzzwords of the new Congress; it would be good for Congress to consider a reform that both makes sense and prevents using the patent system to manipulate the financial markets. Unlike the occasionally arcane minutiae associated with patent law, this is an issue the Congress should understand and know how to correct.

Image of schematic representation of short selling in the two steps (above) by Grochim, from the Wikipedia Commons under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.