Last week, a sensitive internal government document was leaked to the public: the White House Office of Management and Budget’s (OMB’s) passback to the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) laying out proposed funding levels to be included in the fiscal year (FY) 2026 president’s budget. The 64-page leaked document created headlines for two main reasons:

It includes a chart detailing OMB’s vision for how HHS will be restructured (for more on HHS’s restructuring, see this Regs & Eggs blog post.)

It proposes significant cuts to HHS’s discretionary budget, with major reductions across different HHS offices and agencies, and terminations of entire programs.

As health policy stakeholders continue to react to this document, it is important to put it into context, highlighting what it is and isn’t and explaining where we could go from here in arguably unprecedented and unpredictable times.

What Is OMB Passback?

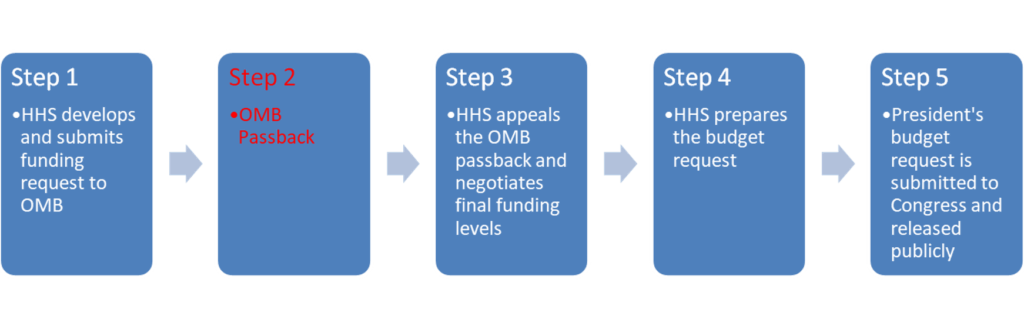

Every year, the administration puts out the president’s budget, which requests funding from Congress for the following fiscal year. The president’s budget has traditionally been an opportunity for the administration to lay out its priorities and state publicly what programs and activities it wants to invest in and which it wants to cut. I worked on eight of these requests during my time at the HHS Budget Office, and the process for creating this document each year is lengthy:

The leaked OMB passback is only step two in the five-step process for creating the president’s budget request. It also only represents the discretionary budget request (discretionary funding is subject to the congressional appropriations process). The president’s budget can also include proposals to revise entitlement programs such as Medicare and Medicaid; adoption of such mandatory legislative proposals requires separate legislation outside of appropriations. Although the leaked OMB passback document doesn’t discuss any legislative proposals, the FY 2026 president’s budget ultimately could include some. Thus, there could be a separate OMB passback for legislative proposals that we haven’t seen.

Before the OMB passback, HHS submitted a budget request to OMB that was not made public. The OMB passback likely reflected some of what HHS initially requested, along with some changes. Once HHS receives the passback, HHS still has a chance to appeal. When appealing, HHS has the ability to ask for changes to funding levels, which OMB can accept or reject. In other words, the OMB passback is a preliminary document that acts as a starting point for negotiations. Once HHS and OMB settle on final funding levels (OMB usually has the final say), HHS begins to prepare the budget. In the first year of a new administration, a “skinny” version of the president’s budget, which includes a high-level overview of the request, is usually released first, followed by the full budget. The skinny version of the FY 2026 president’s budget will likely be released in the next few weeks, and the full FY 2026 president’s budget may be released in May.

What Is It Not?

Historically, the president’s budget is simply a request, and nothing more resolute. Thus, even if we were to suppose that the FY 2026 president’s budget would ultimately include the OMB passback funding levels (i.e., if HHS did not appeal, or if OMB completely rejected HHS’s appeal), the funding levels in the budget usually are not what HHS actually winds up receiving and spending on programs. Although it is extremely useful to understand the administration’s priorities, it is Congress that gets to determine the ultimate funding levels for HHS’s discretionary programs and activities – and Congress can accept or reject all or part of the funding request. In recent years, Congress has rejected the president’s budget request and appropriated the previous year’s funding amount through full-year or part-year “continuing resolutions.” As a result, the president’s budget has not served as an indicator of how much funding HHS programs receive, but only as a guidepost for how the administration would choose to operate programs if it, rather than Congress, could decide.

Where Do We Go From Here?

It is fair to say that the “usual” process may not apply here – and the president’s budget could potentially hold more weight this year than it has historically.

Why is that? Once released, the FY 2026 president’s budget will reflect a vision for HHS that is already being carried out. While President Trump presented budgets during his first term that included significant cuts to discretionary funding and proposed eliminations of certain programs and activities (the FY 2021 president’s budget for example included a 10% reduction to HHS funding levels), the cuts presented in the OMB passback take into account mass reductions in staff that have already occurred and eliminations of programs that HHS has already begun to wind down or deprioritize. In other words, the FY 2026 president’s budget request to Congress may serve more as a formal presentation of what HHS already has done or plans to do anyway, rather than as a true request.

One could argue, though, that the administration can’t do everything it wants to do by itself – and in order to restructure HHS, it needs Congress to take action. For example, the OMB passback requests $14 billion in discretionary funding for the Administration for a Healthy America (AHA) within HHS, which currently does not exist. In theory, the administration is asking Congress to essentially create the AHA by separately appropriating funding for the new entity. However, if Congress ultimately does not formally provide funding for the AHA, can HHS create it anyway? What happens if Congress continues to fund as separate agencies the Health Resources and Services Administration and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration, which HHS plans to eliminate and integrate into AHA? Can HHS eliminate the agencies anyway and use funds appropriated for these agencies to fund the AHA instead? I don’t know the answers to these questions at this point—and it is unclear what would happen if Congress does not structure HHS’s appropriations in line with the administration’s planned restructuring.

The administration has a few tools to carry out its vision for the department if Congress does not play along. The HHS secretary sometimes has the authority to transfer up to 5% of the total HHS appropriation as the secretary sees fit. Further, even after Congress appropriates funding, OMB needs to formally approve and release funds before HHS agencies can spend any money. This approval and release of funds is called the apportionment process. Through this process, OMB can request a plan from HHS on how it plans to spend funding appropriated by Congress, for OMB to review and sign off on before HHS spends any of that funding. OMB can require extremely detailed plans and can carefully craft approvals that limit how agencies can spend funding to ensure that funds are utilized in accordance with the administration’s priorities. In that way, OMB can still exercise significant control over the use of funds even after Congress acts.

Finally, since the administration is already carrying out its vision, it may not be possible for HHS to spend all the funds that Congress appropriates if Congress passes another continuing resolution for FY 2026 or enacts an HHS appropriations bill that includes a funding level that is significantly higher than the FY 2026 president’s budget request. Because of the reductions in staff, contracts, and grants that HHS has already made and will continue to make prior to the start of the new fiscal year, overall HHS operating costs will be lower than in previous years. Even if Congress funds HHS at a certain level, there is no guarantee that this congressionally appropriated level will be the actual funding level at which HHS operates.

The next few months should be telling as the final version of the FY 2026 president’s budget is released and we see how Congress responds. The HHS secretary will have a chance to go before Congress to discuss the request soon after the budget is released. After that, there may be a gap in congressional action. FY 2026 does not begin until October 1, 2025, so Congress may not complete its FY 2026 appropriations process for a while. However, even before Congress acts, HHS may decide to move forward with the creation of new agencies and the elimination of current ones. If the department makes these major moves before the start of the new fiscal year, it would need to figure out how to rearrange funding that Congress already appropriated for FY 2025. And should HHS be successful in this effort, pending any legal or operational challenges, we may be able to assume that the department would take the same approach in FY 2026. All in all, the FY 2026 president’s budget could wind up becoming less of a request and more of an actual operating budget, at least in some areas.

Until next week, this is Jeffrey saying, enjoy reading regs with your eggs.

[View source.]