On May 18, in Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith, the U.S. Supreme Court considered which “use” of a derivative work is relevant for applying the first statutory factor of the fair-use doctrine. The Court held that the first factor requires courts to assess the purpose and character of the challenged use, rather than the purpose the creator had in mind when producing his work and the character of the resulting work. The Court outlined a three-prong test for applying the first factor, addressing whether (1) the secondary use shares a similar purpose with the original work, (2) the secondary use is commercial in nature, and (3) the alleged infringer had some other justification for copying the original work.

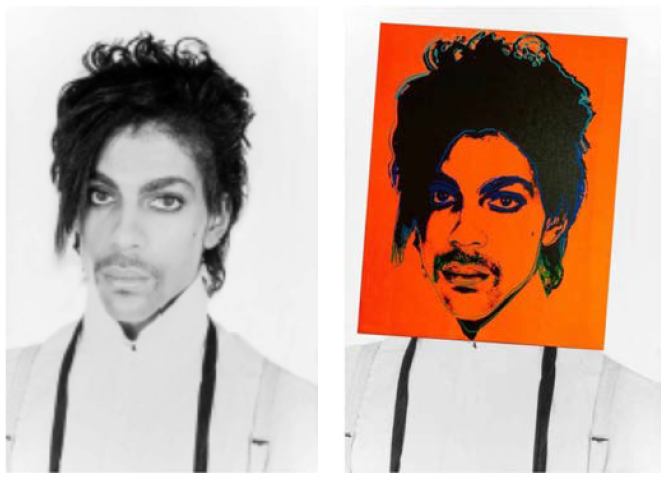

In 1986, professional photographer Lynn Goldsmith granted Vanity Fair a one-time license for a photograph she had taken of the musician Prince. Vanity Fair commissioned artist Andy Warhol to make an illustration based on the photograph, which Vanity Fair published in a subsequent issue accompanying an article about Prince. Warhol then used the photograph to create an unlicensed series of thirteen silkscreen prints, collectively known as the Prince Series. When Warhol died in 1987, ownership of the Prince Series passed to the Andy Warhol Foundation (AWF). In 2016, Vanity Fair’s parent company, Condé Nast, purchased a license from AWF to use one of the Prince Series pieces, Orange Prince (shown below), on the cover of a special edition magazine commemorating the late Prince. When Goldsmith saw Orange Prince on the cover of Condé Nast’s magazine, she informed AWF that it had infringed her copyright. In response, AWF sued Goldsmith for a declaratory judgment of noninfringement or, in the alternative, fair use. Goldsmith counterclaimed for infringement.

Warhol’s Orange Prince superimposed over Goldsmith’s original photograph. Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith.

A district court, applying the 1976 Copyright Act’s four-factor test for analyzing fair use, found that AWF’s use of Goldsmith’s copyrighted work was fair, and granted summary judgment for AWF. Goldsmith appealed, and the Second Circuit reversed, holding that all four statutory factors weighed in favor of Goldsmith. AWF then petitioned for a writ of certiorari to the Court challenging the Second Circuit’s application of the first factor, particularly its holding that recasting an original work in a new aesthetic form is not transformative.

The question before the Court was whether the Second Circuit correctly held that the first fair use factor — “the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes” — weighed in favor of Goldsmith. In answering, the Court clarified which particular use of Goldsmith’s original work was at issue in this case. At the trial and appellate level, both parties’ claims concerned the entire Prince Series, and whether Warhol’s creation thereof infringed Goldsmith’s copyright. In Goldsmith’s Respondent’s Brief, however, Goldsmith abandoned all her claims to relief other than for the claim pertaining to AWF’s licensing of Orange Prince to Condé Nast, thus narrowing the issue for the Court. The Court explained, therefore, that, while Goldsmith’s original work had been used in multiple ways, only this single use was presently alleged to be infringing. The Court emphasized that its decision dealt solely with AWF’s right to license Orange Prince, not with Warhol’s right to create, display, or sell it.

Building upon its decision in Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc., the Court delineated a three-prong test for analyzing the first fair use factor, holding that, if “an original work and a secondary use share the same or highly similar purposes, and the secondary use is of a commercial nature, the first factor is likely to weigh against fair use, absent some other justification for copying.” Applying the factors to the present case, the Court found that Goldsmith’s photograph and AWF’s use thereof had essentially the same purpose—portraying Prince in a magazine story about Prince. The Court noted that although Orange Prince may have originally been intended to convey a different message than Goldsmith’s photograph, this distinction was insufficient to alter the fundamental, objective purpose of the use in question. Secondly, the Court found AWF’s licensing of Orange Prince to be indisputably commercial in nature. Thirdly, the Court found that, unlike parodies that inherently necessitate a certain degree of copying to target an original work, AWF had no like justification for its use of the photograph. Accordingly, the Court held that the first factor weighed against a finding of fair use.

In reaching its conclusion, the Court rejected AWF’s argument that Orange Prince was a transformative use. AWF asserted that Warhol reinterpreted Goldsmith’s photograph—depicting Prince as an iconic, larger-than-life figure, conveying the dehumanizing nature of celebrity—and that this “new expression, meaning, or message” tipped the first factor in favor of fair use under Campbell. The Court explained that the mere addition of a new meaning or message could not independently establish transformativeness under Campbell. Rather, the Campbell criteria should be viewed as indications, not absolute proof, of transformativeness. Moreover, the Court held that this sort of subjective argument based on artistic significance is largely irrelevant, because Warhol’s artistic input in the creation of the piece has little bearing on AWF’s present use of the piece. Rather than assume the role of art interpreters, explained the Court, judges are to determine fair use via a purely objective analysis.

This decision articulated a new analytical standard for the first factor of the fair use doctrine, which is centered on whether (1) the secondary use shares a similar purpose with the original work, (2) the secondary use is commercial in nature, and (3) the alleged infringer had some other justification for copying the original work. These facts can be the sole determinants of whether a use is found to be fair, irrespective of how similar, transformative, or artistically significant the derivative work is.