The regulatory environment at the US Food and Drug Administration (“FDA”) has a tremendous impact on how companies operate, and consequently data on that environment can be quite useful in business planning. In keeping with the theme of these posts of unpacking averages, it’s important to drill down sufficiently to get a sense of the regulatory environment in which a particular company operates rather than rely on more global averages for the entire medical device industry. On the other hand, getting too specific in the data and focusing on one particular product category can prevent a company from seeing the forest for the trees.

Recently, I was asked by companies interested in the field of digital medical devices used in the care of people with diabetes to help them assess trends in the regulatory environment. To do that, I decided to create an index that would capture the regulatory environment for medium risk digital diabetes devices, trying to avoid getting too specific but also avoiding global data on all medical devices. In this sense, the index is like any other index, such as the Standard & Poor 500, which is used to assess the economic performance of the largest companies in terms of capitalization. My plan was to first define an index of product codes for these medium risk digital diabetes products, then use that index to assess the regulatory environment in both premarket and postmarket regulatory requirements.

Creating the Index

Product codes are the language of FDA regulation. Every medical device FDA regulates is placed into a product code. If there isn’t a product code for a new device, FDA has to create one, often through the de novo process. Roughly 2100 device classifications found in the regulations are further subdivided into over 6700 product codes, and they are organized roughly by medical specialties such as anesthesiology, clinical chemistry and general surgery.

While medical specialties can be useful groupings, each of them is also quite broad and none of them are disease specific. As a result, if your company is focused, for example, on products for diabetes, the diagnostic codes might be in one or two different medical specialties while the therapeutic products might be in yet a different medical specialty grouping. More problematic, if your focus is diabetes, those medical specialties will be far too overbroad to be useful for assessing the relevant regulatory environment.

For prior posts, I created a database of the 510(k) summaries submitted to FDA. Using that database, I began by searching for the word ‘diabetes,’ but also words and phrases like ‘insulin’, ‘diabetic retinopathy’, ‘diabetic nephropathy’, and ‘diabetic neuropathy’. My search also included more exotic terms just to make sure that it was comprehensive, using the PubMed MeSH (medical subject headings) framework to identify synonyms and related conditions.

My focus was on digital diabetes products, so I then separately searched for the word ‘software.’ I reasoned that it was highly likely that any digital product would at least mention the word ‘software’ in the summary, although technically it’s also possible that someone might have written that ‘our product includes no software.’ Given that the trend is toward digital, it seemed unlikely to me that very many submissions would include the phrase “no software” as if to brag about being lower tech, but it is possible.

At the end, I chose the product codes that were at the intersection of the two different searches. That process produced a list of roughly 50 product codes.

I wanted to focus the list so as to not include products that were only tangentially related to digital devices for diabetes, so I took two additional steps. First, I divided the number of submissions in each product code that mention diabetes by the total number of submissions. I reasoned that this would give me a percentage of submissions in a given product code that mentioned diabetes, which would be a good bellwether for the relevance of the product code for my purpose. Second, I consulted some clinical experts to ask them what they would consider out of my list to be the most relevant product codes for this purpose. In this project, for example, many wound treatment products mentioned diabetes, but the experts didn’t consider wound treatment to be truly a diabetes product.

At the end of this process, I came up with an index based on the following 30 product codes as representing medium risk digital diabetes medical devices.

I was focused on medium risk, because quite frankly there are large differences in regulatory environments between class I, class II and class III medical devices (ranging from products that are exempt from premarket review to those that require premarket approval), and the people with whom I was speaking were largely in the medium risk business.

Using the Index

Having defined my index by product codes, that index then allowed me to see how that category performs broadly in just about any dimension for which FDA produces data. For example, I wanted to first see how these medium risk digital diabetes medical devices fair in terms of FDA review times.

The black lines are the 30 digital diabetes product codes. What looks like a blue area is actually 6600 vertical blue lines representing the average review time within each product code sorted from shortest to longest. The shortest average review time for a single product code is just over 50 days, and the longest average review time for a particular product code is over 500 days.

The digital diabetes products are clustered toward the long review end. The average is marked by the dotted line, and the digital diabetes products are all well above average. And you can see why I do this, because there really is no such thing as a typical medical device review time. Instead, they vary widely depending on the product codes.

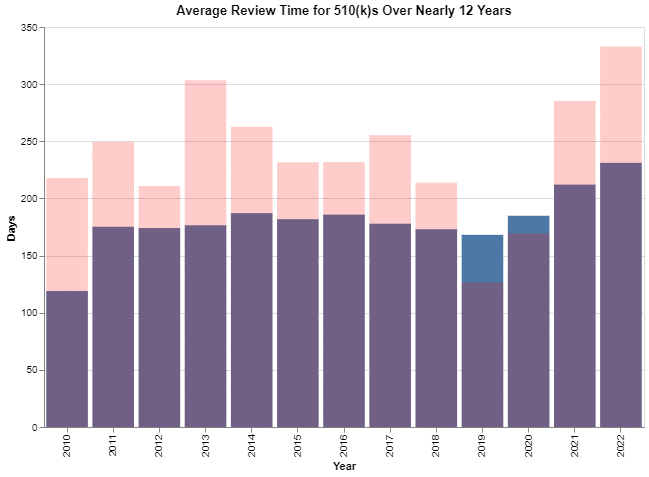

Having seen this, I was interested in whether this pattern changes over time. The chart above was simply the averages over about 12 years’ worth of data (2010-2022). In the chart below, I broke it down by year.

These are calendar years, and I did the analysis in October 2022, so that year is a partial year.

The colors require a bit of explanation because I only used two colors. I used pink to depict the digital diabetes index review times, and I picked blue to represent the averages for all medical devices. This makes it easy to see that in all but two years, the pink review times – the digital diabetes review times – exceeded the average for all medical devices typically by a wide margin. But in two years – 2019 and 2020 – the averages for all medical devices exceeded the review times for digital diabetes products. Honestly, I have no idea why 2019 and 2020 were different from the overall trend.

Looking at the data, naturally I wondered why FDA was so slow in its review of digital diabetes products in comparison to the overall averages. To look for an answer, I studied the data on the postmarket experience for these products. Specifically, I examined the number of medical device reports filed for the indexed digital diabetes product codes versus all the other product codes.

Here, to make the visualization more readable, I only focused on the 20 worst medical device product codes, where “worst” means those having the greatest number of medical device reports (“MDRs”) filed in a given year. Thus, these are the ones that FDA has the greatest concern with regard to product safety and effectiveness. I picked 2021 because that was the most recent complete year of data that I had.

You’ll notice that the magnitude of the number of MDRs falls rapidly by product code. The black bars are the product codes from the digital diabetes index. There are five product codes among the top 20 that are included in the digital diabetes space.

I don’t want to deal with this complex issue too simplistically. It is beyond the scope of this post to analyze why these data are the way they are. I think most people recognize that people with diabetes have many challenges in that many of them are elderly and have limited vision and manual dexterity, making it difficult for them to use medical devices of various sorts. Also, obviously, the sheer number of people with diabetes means that there are many of these products in circulation at any one time.

While I don’t mean to dismiss the need for a more nuanced assessment of the data, I would simply point out from a big picture perspective that these data are what FDA looks at in the postmarket experience, and this experience probably contributes to FDA’s conservatism in how they review new product submissions in this category.

Conclusion

Often it’s important when looking at the data to not look at the medical device industry as a whole as if it’s homogenous, nor to zero in too closely on individual products and product codes when trying to discern FDA trends. Creating an index is one way that a company can track the relevant regulatory environment in which it operates. And that tracking can produce insights about what the industry generally needs to do at a high level and what they can expect from FDA regulation.

[View source.]