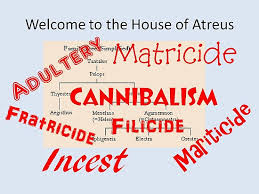

Not much beats the ancient Greek House of Atreus for dramatic gore: infanticide, patricide, fratricide, filicide, matricide, cannibalism, incest and about every other horror which can befall one family occurs in the various stories of this, the ruling family of Mycenae. One of the most horrific stories involves the brothers Atreus and Thyestes. After Atreus steals the throne from Thyestes, Thyestes seeks his revenge by sleeping with Atreus’ wife Aerope. Atreus then invites Thyestes to a reconciliation banquet where he serves the roasted heads of Atreus’ two sons on platters as the main course. Atreus then puts a curse on Atreus and all his offspring, which lasted throughout Greek antiquity (i.e. longer than the Curse of the Bambino or Curse of the Billy Goat). To this day a Thyestean Feast is synonymous as cannibalistic feast. In other words, at what cost did you really prevail?

Not much beats the ancient Greek House of Atreus for dramatic gore: infanticide, patricide, fratricide, filicide, matricide, cannibalism, incest and about every other horror which can befall one family occurs in the various stories of this, the ruling family of Mycenae. One of the most horrific stories involves the brothers Atreus and Thyestes. After Atreus steals the throne from Thyestes, Thyestes seeks his revenge by sleeping with Atreus’ wife Aerope. Atreus then invites Thyestes to a reconciliation banquet where he serves the roasted heads of Atreus’ two sons on platters as the main course. Atreus then puts a curse on Atreus and all his offspring, which lasted throughout Greek antiquity (i.e. longer than the Curse of the Bambino or Curse of the Billy Goat). To this day a Thyestean Feast is synonymous as cannibalistic feast. In other words, at what cost did you really prevail?

I thought about the above myth in the context of the arrest of two articles I wrote about yesterday which appeared in the Weekend Edition of the Financial Times (FT) about the arrest of Frederic Cilins, a French citizen, for seeking to obstruct a federal grand jury investigation about alleged Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA) violations. The two articles were “Contracts link BSGR to alleged bribes” (mine rights article) and “FBI sting says that ‘agent’ sought to have mining contracts destroyed” (FBI sting article). Both articles were by the same triumvirate of FT reporters, Tom Burgis, Misha Glenny and Cynthia O’Murchu.

To recap, the articles revolved around allegations that “The resources arm of Beny Steinmetz Group agreed to pay $2m to the wife of an African president to help it secure rights to one of the world’s richest untapped mineral deposits, according to documents seen by the Financial Times”. These payments were allegedly memorialized in “Copies of two contracts from 2007 and 2008, apparently signed by BSGR’s representatives in the mineral-rich west African nation of Guinea, set out agreements for the company to make payments and transfer shares to Mamadie Touré, wife of the then president Lansana Conté.”

The FBI sting article also revealed a bit more of the history of the underlying mining rights at issue. The Australian company Rio Tinto “held the rights to the whole of Simandou, a mountain range groaning with iron ore in Guinea’s remote interior, for a decade.” But in August, 2008, the Conté government withdrew the mining group’s concession, “saying it had taken too long to develop a mine.” In December 2008, just days before the dictator’s death, the then Guinean government assigned over half the rights of Simandou to BSGR. The FT also reported that “One African mining veteran described BSGR’s sale as the “best private mining deal of our generation.”” After spending $160m developing its assets in Guinea, 18 months later, in April 2010, BSGR sold a 51% stake of its Guinean venture to Vale of Brazil for $2.5bn.

The FT also reported that after the transfer of mining rights from Rio Tinto to BSGR, another mining entity, “Vale of Brazil, the world’s biggest iron ore miner, bought a 51 per cent in BSR’s Guinea assets in April 2010. Late last year, as a Guinean government committee levelled corruption allegations against BSGR, Vale put the Simandou project on hold. Earlier this month, it suspended payments on the $2.5bn it agreed to pay for its stake.”

Now all of the above are only allegations at this point and BSGR has clearly stated that it believes the allegations have no merit. As the mining rights article noted, “BSGR said in a statement to the FT on Friday: “Allegations of fraud in obtaining our mining rights in Guinea are entirely baseless. We are confident that BSGR’s position in Guinea will be fully vindicated.””

But under such a scenario, what might be the cost to be to a company which engages in such conduct. Fortunately we have somewhat evolved past the blood feuds that the ancients Greeks engaged in were they wronged. We have developed the litigation system to help redress violations of law. In an interesting note, even this was foreshadowed in the Greek myths where the final play about the House of Atreus involved a trial rather than blood revenge.

In the above scenario, what might be some of the legal rights of the parties listed? In an article entitled “Use of the FCPA in State-Law Unfair Competition Cases”, Edward Little, Jr. explored the question of whether the FCPA can serve as the basis as a predicate act for civil liability under state unfair competition laws. He makes a powerful case that such lawsuits may be the next frontier for FCPA cases.

Little next noted that the violation of the FCPA may provide a basis for civil liability under federal or state anti-trust laws, “especially when it is proved that the foreign bribery had an anti-competitive effect within the United States.” Little pointed to the example of two Phillip Morris subsidiaries that bribed officials in several South American countries “to obtain price controls on tobacco.” There was also a recent FCPA/anti-trust enforcement action against Bridgestone which may provide such a trigger.

Little turned to state unfair competition laws which, if based on the Revised Uniform Deceptive Trade Practices Act, can “provide severe penalties for violations of federal and state laws when committed in trade or commerce.” These penalties can include treble damages and attorneys’ fees. He pointed to a currently pending litigation matter styled “Newmarket Corp. v. Innospec, Inc. Civil Action No. 10-503-HEH (E.D Va.)” in which Newmarket has brought claims under the Sherman Act, the Robinson-Patman Act and the state of Virginia Business Conspiracy Act. This state law makes illegal “combinations of two or more persons for the purpose of willfully and maliciously injuring another in his…business…”

Most states have some type of law which broadly declares that “unfair methods of competition are…unlawful.” If a company admits to guilt under the FCPA the facts of liability are laid out in a Deferred Prosecution Agreement (DPA). There is some discussion of the amount of bribes paid, usually referencing both the monetary value of the contract or other business obtained through the conduct, which laid the predicate for the FCPA violation. Lastly, there is often a specific amount of money identified as profit disgorgement that is remitted to the government. Doesn’t this sound something like “Did the defendant engage in illegal conduct which impacted the plaintiff?” and “If so, what are the plaintiff’s damages?”

As a recovering trial lawyer, I was proud to engage in a profession which can trace its roots back to ancient Greece. As a lawyer, who specializes in the FCPA, I wonder if a company which uses corruption and bribery to steal or even procure a contract or business might find that the cost of obtaining such business is too high if they are forced to defend themselves in a civil trial and pay out the amount of damages that their conduct caused. Indeed, might it even be the modern day equivalent to a Thyestean Feast?