There is no demand for legal services.

Now that I have your attention, I’ll clarify. There’s no demand for legal services per se. Nobody wakes up in the morning saying, “Let’s buy some ‘litigation’ today.” There’s no demand for legal service nouns.

Demand is the byproduct of relevance, usefulness, and value. Those attributes derive from a client’s need to solve a problem or exploit an opportunity. Without that context, legal service is irrelevant. It has no inherent usefulness or value, which are descriptions of impact. If we have no impact, we’re neither useful nor valuable. If there’s no problem or opportunity, there’s nothing to impact, and legal service has no relevance. If we have no relevance, there’s no reason to speak with us.

It’s not who you know, but who knows you and what they know you for. That’s completely within your control.

Relevance

Too many lawyers attempt to get on prospects’ calendars to discuss some legal service or another. Without realizing it, they’re asking someone to allocate a portion of a busy day to discuss what, absent any correlation to a business challenge, is irrelevant to that day. This is why it’s hard to get appointments, and why they’re so often rescheduled or cancelled.

Most lawyers aspire to be indispensable to clients. That’s the ultimate defense against attempts by competitors to displace you. Indispensability depends on a progression of increasing levels of impact.

I call that progression the Impact Ladder. Progress is earned, in sequence. The first rung, Relevance, is the foundation predicate, and the only one of the four statuses that you can initiate and influence directly. All subsequent ones are at the sole discretion of the prospect or client.

How to earn relevance

The Door-Opener is the mechanism for earning relevance. It’s the underlying business problem or opportunity that triggers demand for specific legal services. It’s a literal term because it opens the door to a demand-driving business conversation with a prospect or client (or an entire market segment) that you can sustain long enough for buyers to associate you with it and think of you when the problem becomes acute enough to require action. It sets up the bridge between marketing and selling.

Your “Door-Opener” is not just any business challenge that’s relevant to desirable prospects and clients, but one that yields a practice that you love, that really gets your juices flowing in the morning. This problem’s relevance literally opens doors to conversations with decision-makers whose job it is to explore solutions to these high-impact challenges. Now, instead of begging for an audience where you’ll interrupt someone’s job with a pitch, you’re now welcomed as a contributor to their job.

Insert yourself into the conversation early -- and stick around

You need to identify -- and associate yourself with -- business issues before they’re legal issues. Descriptive legal-service nouns, e.g., “Litigation” or “M&A,” are not to your advantage because they exclude you from conversations that matter. They also reinforce the position of incumbent law firms and lawyers whose names are already associated with those nouns in that buyer’s mind.

Descriptive legal-service nouns, e.g., “Litigation” or “M&A,” are not to your advantage because they exclude you from conversations that matter.

For example, here’s Marcia, a fictitious attorney specializing in IP and trade secret litigation. Her Door-Opener is the condition of scarce technical talent being recruited to move between competing companies in Silicon Valley, unavoidably taking the intellectual property in their brains with them.

Why does this problem open doors for someone like Marcia, and eventually lead to demand for her services?

With all the talent moving around, it's certain that some of the companies losing talent will be suspicious of any technical advances by companies who hired their people, particularly if the advances fall within the expertise of the workers recruited from them. Some of those companies will attribute at least part of any market misfortunes they experience to the knowledge inside their former engineers' heads.

All Marcia has to do is continually beat the drum about the “talent war” problem, its impact and what software companies should do to avoid it, minimize it or recover from it. Even if a software executive who lost a key engineer and suffered market shrinkage somehow knows 20 intellectual property lawyers, they don't see this as an “IP” problem, but as a “key software developer moving to a competitor” problem. Because most lawyers identify themselves with a legal service noun, Marcia is likely the only lawyer they’ve heard talking in terms that are meaningful to them.

“The Boss” and his IP lawyers

Let’s look at a real case. In Bruce Springsteen's 2005 Rock & Roll Hall of Fame induction acceptance speech, he thanked many people, including his IP lawyers. How he phrased it is instructive:

“Now the lawyers -- gotta thank them. Peter Parcher and Steve Hayes. They protected me and my music for 22 years.”

The Boss didn't say “they did great intellectual property work.” Other than IP lawyers, that's not how people talk. He cited how their work affected him.

Is Bruce Springsteen an outlier, the only songwriter concerned about others making unfair commercial use of his work? Obviously not. There’s nothing to prevent Parcher and Hayes from using Springsteen’s remark as the basis for a Door-Opener that positions them as relevant to songwriters. They could write articles about it, speak at music industry conferences, post about it in their blog and syndicate those posts in social media outlets and music-related LinkedIn groups, and other channels that reach songwriters -- and their advisors, collaborators, investors, and business partners.

How long do you think it would take for the word to get around among performers and songwriters that a) you’re at risk of having your work stolen, and b) these lawyers seem to understand this problem and how to prevent it?

The Door-Opener is industry-specific. It reliably affects members of a class, in this case, songwriters. It creates demand for the service category, i.e., IP protection. It doesn’t create demand for Parcher and Hayes specifically, but it raises the odds substantially. If you’re a songwriter who, as a result of their communications, has become much more aware of this threat and, over time, the different examples and permutations they’ve shared have given you a much richer appreciation of the problem, sufficient for you to conclude, “I’d better do something to protect my music,” isn’t it likely that Parcher and Hayes are the only lawyers you associate with this issue? Would you discuss it with them, or would you instead go hunting for other lawyers who might also know something about this threat?

It’s about relevance, not relationships

For the 25 years I’ve coached lawyers, I’ve heard the mantra, “It’s all about relationships,” where relationships meant personal ones, or friendships.

That may have been true during the span that The American Lawyer magazine called “the Golden Age of Law Firms.” Everyone was buying and all you needed to succeed was, in the words of one of my first clients, “a helluva lot of friends.” Under such optimal conditions, relationship-building (making friends) worked just fine. Buyers had the luxury of buying at least a little from almost all their friends.

However, the Great Recession of 2008 triggered the shift from a seller’s market to a buyer’s market. Now, buyers have more lawyer friends than legal budget. Yet, lawyers still conduct themselves as if a personal relationship is a necessary predicate for a business relationship. It’s not. Many buyers don’t have time for traditional relationship-building. They’re too busy doing the job of two people.

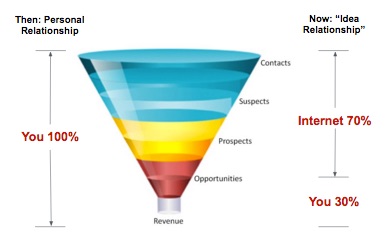

The definition of “relationship” has changed. Now, instead of relating to a person, you must relate to that person’s job in a way that they can see you as relevant to their success. The relationship is with your ideas, not you, and it’s developed primarily online.

Studies show that as much as 70% of the information-sharing and personal relationship-building that salespeople used to do in person and by phone has been replaced by online activity. More importantly, buyers now prefer not to have contact with sellers until they’ve made that progress on their own. You have to have an online conversation presence.

At least some of the songwriters in the example above, who were repeatedly exposed to Parcher’s and Hayes’s posts, would have formed a virtual relationship with those lawyers as a result of their relationship with their ideas about protecting music. Most have no personal relationship with the lawyers, couldn’t pick them out of a lineup, and may never have a desire for a personal relationship with them or any other lawyer.

Your Door-Opener is the key to relevance, and with it to virtual relationships with many thousands of people simultaneously, asynchronously, with no geographic or time boundaries.

Weak Door-Openers

Your Door-Opener must reflect the actual world and language of your target market. If it doesn't sound like them, it won't resonate with them, and you won't matter to them.

Being reflective of the market is necessary, but not sufficient. Even if a problem you're considering for your Door-Opener reflects the actual world and language of your target market, it still may spur little demand for your services. How? If it’s too vague, broad, impersonal or intangible, it will have no motivating power.

Returning to the software business, consider a business issue that's caused billions in corporate waste for years. A number of years ago, a Standish Group study concluded that “Fortune 100 companies last year canceled 33 out of every 100 software projects and ran over budget or beyond deadline on another 40 applications. All told, the development fiascoes cost $145 billion.”

Is this a good Door-Opener? A business issue that has caused billions in corporate waste for years is tempting because of its economic magnitude. For the individuals you hope to motivate to act, however, the issue has no immediacy; it’s already been factored into the cost of doing business. No one's going to be a hero for fixing it—or blamed for not. The wasted dollars are institutional, abstract. They're not coming out of this person's budget or bonus directly. So, it's not personal.

Unless the corporate pain also creates personal pain for the individual buyer, it’s an intellectual concept that rarely commands action. Find a better Door-Opener. Make sure it’s tangible, immediate and personal.

Tangible, immediate, personal

Let’s go back to Marcia, our IP lawyer. She’s positioned as the “key talent moving to competitors and taking what they know with them” expert. Her Door-Opener is absolutely tangible, immediate and personal.

Tangibility is shown by the fact that you can visualize the problem. Can you see Stan, a 30-year-old software wizard, turning in his resignation at MegaTech, then two weeks later turning on his computer at AdvoTech? Can you visualize MegaTech management reading an AdvoTech new-product announcement, seeing what looks like Stan's fingerprints on the innovation?

Immediacy? All the tech media in Silicon Valley are talking about talent movement every day. This is no “someday, maybe” abstraction; it's happening right now.

The personal aspect is also clear. Software is a fiercely competitive business. Companies that fall behind technologically may face job losses, even extinction. The competitive nature of the business means there are individual winners and losers every day.

Marcia has a strong Door Opener. Next, she must find an audience. One audience. She must focus on one discrete market.

In the past, when people have asked you what type of attorney you are, what's been your standard answer? If you’re candid, you’ll admit you use one of the legal-service nouns, e.g., “litigator,” “corporate lawyer,” etc. This traps you as one of tens- or hundreds of thousands of anonymous practitioners wearing that broad label. Differentiation has been soundly defeated.

Pursue v. Accept

You can still accept any matter you’re qualified to handle, that pays your fees, and that you find interesting, but with the limited amount of time you have to write, speak, and sell, you can only pursue a finite group of potential clients for whom there are organized communication channels – such as events, media, organizations, etc. You can't market to “everyone;” there are no communication channels that reach “everyone.”

To enable an audience to feel like they know your ideas about a class of issues they care about, how many times do you think they must be exposed to you in a year? Recent research suggests it’s 10-12 times a year, whether in person, in print, electronically, by phone, or just being mentioned in discussion within the industry. Given the time and resource constraints lawyers face, it's virtually impossible to become reliably associated with an issue if you don’t focus your effort in a single place.

You focus on one industry to minimize the amount of context you must acquire and refresh, to maximize the effectiveness of your marketing and sales investment, to yield the largest number of new clients each year, and new matters from existing clients.

If you do a good job for those clients, they’ll refer you to their peers in other industries who have problems you can solve. Talent is mobile; people switch industries all the time. If you did a great job on a transaction for someone in the manufacturing industry who then moves into the equipment leasing space, he isn't going to hold your expertise in the manufacturing industry against you.

One of the most successful attorneys I’ve coached made a name for himself in the Aerospace industry. He had the legal column in the top industry publication, spoke at the big conference every year, and received accolades as one of the top five Aerospace attorneys in the U.S. The joke around his firm, though, was that his practice was only about 25% Aerospace. Through referrals and clients moving around, he ended up with an incredibly diverse corporate practice.

Until he had a chance to perform for a new client, he needed an easy way to be remembered and found by the maximum number of prospects. His aerospace industry focus made that happen.

...industry knowledge is the only way to protect yourself against service obsolescence or budget constraints

An additional advantage of being perceived as an industry expert is the variety of case types that occur within that industry. What would be odd about an aerospace executive talking to an attorney who is an aerospace expert about business problems that translate into litigation, employment, IP, real estate, and benefits issues in that business? You’ll naturally bring in business for other specialists in your firm, and you’ll eliminate the agony of cross-selling.

Finally, industry knowledge is the only way to protect yourself against service obsolescence or budget constraints. Industry expertise allows you to spot emerging problems that earn you access to otherwise unavailable executives, and yield interesting work that, by definition, is outside the legal budget but for which they will always find the money for solutions because of the impact of the underlying business problem.

This is, in fact, how I ended up in the lawyer sales coaching business, and it shows how the “find the money if needed” effect works. I was in the sports business, selling sponsorships for professional tennis tournaments. Someone told me about a big litigation firm, few of whose clients were located in their city, and who had limited chances to spend time with clients off the clock to get to know them and learn about opportunities. As you’ve seen with the US Open and other events, pro tennis attracts a corporate demographic. Recognizing that their clients would be willing to come into town and spend four hours with them at a significant event like this, the firm invested $150,000 for the use of a catered courtside suite for seven years. I’m certain there was no line item in the firm’s budget for a tennis sponsorship, but they recognized the importance of the problem they could solve, and found the money somewhere.

The lesson here: If you’re hearing, “There’s no budget,” you’re discussing the wrong problem with the wrong people. The right problem (one with unacceptable consequences) will attract the right people -- and the money to solve it.

*

[Mike O'Horo is the co-founder of RainmakerVT and has trained 7000 lawyers in firms of all sizes and types, in virtually every practice type. They attribute $1.5 billion in additional business to their collaboration. His latest innovation, Dezurve, reduces firms’ business development training investment risks by identifying which lawyers are serious about learning BD.]